2.2 Descriptive Studies: Establishing the Facts

Psychologists gather evidence to support their hypotheses by using different methods, depending on the kinds of questions they want to answer. These methods are not mutually exclusive, however. Just as a police detective may rely on DNA samples, fingerprints, and interviews of suspects to figure out “who done it,” psychological sleuths often draw on different techniques at different stages of an investigation. The video How to Answer Psychological Questions will help you sharpen your investigative skills.

Watch

How to Answer Psychological Questions

Research Participants

One of the first challenges facing any researcher, no matter what method is used, is to select the participants (sometimes called “subjects”) for the study. Ideally, the researcher would prefer to get a representative sample, a group of participants that accurately represents the larger population that the researcher is interested in. Suppose you wanted to learn about drug use among first-year college students. Questioning or observing every first-year student in the country would obviously not be practical; instead, you would need to recruit a sample. You could use special selection procedures to ensure that this sample contained the same proportion of women, men, blacks, whites, poor people, rich people, Catholics, Jews, and so on as in the general population of new college students. Even then, a sample drawn just from your own school or town might not produce results applicable to the entire country or even your state.

Plenty of studies are based on unrepresentative samples. The American Medical Association reported, based on a “random sample” of 664 women who were polled online, that binge drinking and unprotected sex were rampant among college women during spring break vacations. The media had a field day with this news. Yet the sample, it turned out, was not random at all. It included only women who volunteered to answer questions, and only a fourth of them had ever taken a spring break trip (Rosnow & Rosenthal, 2011).

A sample's size is less critical than its representativeness. A small but representative sample may yield accurate results, whereas a large study that fails to use proper sampling methods may yield questionable results. But in practice, psychologists and others who study human behavior must often settle for a sample of people who happen to be available—a “convenience” sample—and more often than not, this means undergraduate students. One group of researchers noted that most of these students are WEIRDos—from Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic cultures—and thus hardly representative of humans as a whole. “WEIRD subjects are some of the most psychologically unusual people on the planet,” said one of the investigators (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010).

College students, in addition, are younger than the general population. They are also more likely to be female and to have better cognitive skills. Does that matter? It depends. Many psychological processes, such as basic perceptual or memory processes, are likely to be the same in students as in anyone else; after all, students are not a separate species, no matter what they (or their professors) may sometimes think! When considering other topics, however, we may need to be cautious about drawing conclusions until the research can be replicated with nonstudents. Scientists are turning to technology to help them do this. Amazon runs a site called Mechanical Turk, where people across the world do online tasks that computers cannot do, typically for small rewards that they usually convert into Amazon vouchers. Many of the 500,000 registered Turk workers also participate in research, allowing scientists to quickly and cheaply recruit a diverse sample of thousands of people (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011). One research team was able to analyze the patterns of moods in people's tweets worldwide (Golder & Macy, 2011).

We turn now to the specific methods used most commonly in psychological research. As you read about these methods, you may want to list their advantages and disadvantages so that you will remember them better. Then check your list against the one in Review2.1. We begin with descriptive methods, which allow researchers to describe and predict behavior but not necessarily to choose one explanation over competing ones.

Case Studies

A case study (or case history) is a detailed description of a particular individual based on careful observation or formal psychological testing. It may include information about a person's childhood, dreams, fantasies, experiences, and relationships—anything that will provide insight into the person's behavior. Case studies are most commonly used by clinicians, but sometimes academic researchers use them as well, especially when they are just beginning to study a topic or when practical or ethical considerations prevent them from gathering information in other ways.

Suppose you want to know whether the first few years of life are critical for acquiring a first language. Can children who have missed out on hearing speech (or, in the case of deaf children, seeing signs) during their early years catch up later on? Obviously, psychologists cannot answer this question by isolating children and seeing what happens. So, instead, they have studied unusual cases of language deprivation.

One such case involved a 13-year-old girl who had been cruelly locked up in a small room since the age of 1½, strapped for hours to a potty chair. If she made the slightest sound, her severely disturbed father beat her with a large piece of wood. When she was finally rescued, “Genie,” as researchers called her, did not know how to chew or stand erect and was not toilet-trained. Her only sounds were high-pitched whimpers. Eventually, she began to understand short sentences and to use words to convey her needs, but even after many years, Genie's grammar and pronunciation remained abnormal. She never learned to use pronouns correctly, ask questions, or use the little word endings that communicate tense, number, and possession (Curtiss, 1977, 1982; Rymer, 1993). This sad case, along with similar ones, suggests that a critical period exists for language development, with the likelihood of fully mastering a first language declining steadily after early childhood and falling off drastically at puberty (Pinker, 1994).

Case Studies

Case studies illustrate psychological principles in a way that abstract generalizations and cold statistics never can, and they produce a more detailed picture of an individual than other methods do. In biological research, cases of patients with brain damage have yielded important clues to how the brain is organized. But in most instances, case studies have serious drawbacks. Information is often missing or hard to interpret; no one knows what Genie's language development was like before she was locked up or whether she was born with mental deficits. The observer who writes up the case may have certain biases that influence which facts are noticed or overlooked. The person who is the focus of the study may have selective or inaccurate memories, making any conclusions unreliable (Loftus & Guyer, 2002). Most important, because that person may be unrepresentative of the group the researcher is interested in, this method has only limited usefulness for deriving general principles of behavior. For all these reasons, case studies are usually only sources, rather than tests, of hypotheses.

Many psychotherapists publish individual case studies of their clients in treatment. These can be informative, but they are not equivalent to scientific research and can sometimes be wrong or misleading. Consider the sensational story of “Sybil,” whose account of her 16 personalities became a famous book and TV movie, eventually launching an epidemic of multiple personality disorder. Detective work by investigative journalists and other skeptics later revealed that Sybil was not a multiple personality after all; her diagnosis was created in collusion with her psychiatrist, Cornelia Wilbur, who hoped to profit professionally and financially from the story (Nathan, 2011). Wilbur omitted many facts from her case study of Sybil, such as the vitamin B12 deficiency that produced Sybil's emotional and physical problems. Wilbur did not disclose that she was administering massive amounts of heavy drugs to her patient, who became addicted to them. And she never informed her colleagues or the public that Sybil had written to her admitting that she did not have multiple personalities.

Be wary, then, of the compelling case histories reported in the media by individuals or by therapists. Often, these stories are only “arguing by anecdote,” and they are not a basis for drawing firm conclusions about anything.

Observational Studies

In observational studies, a researcher observes, measures, and records behavior, taking care to avoid intruding on the people (or animals) being observed. Unlike case studies, observational studies usually involve many participants. Often, an observational study is the first step in a program of research; it is helpful to have a good description of behavior before you try to explain it.

The primary purpose of naturalistic observation is to find out how people or animals act in their normal social environments. Psychologists use naturalistic observation wherever people happen to be—at home, on playgrounds or streets, in schoolrooms, or in offices. In one study, a social psychologist and his students ventured into a common human habitat: bars. They wanted to know whether people in bars drink more when they are in groups than when they are alone. They visited all 32 pubs in a midsized city, ordered beers, and recorded on napkins and pieces of newspaper how much the other patrons imbibed. They found that drinkers in groups consumed more than individuals who were alone. Those in groups did not drink any faster; they just lingered in the bar longer (Sommer, 1977).

Note that the students who did this study did not rely on their impressions or memories of how much people drank. In observational studies, researchers count, rate, or measure behavior in a systematic way, to guard against noticing only what they expect or want to see, and they keep careful records so that others can cross-check their observations. Observers must also take pains to avoid being obvious about what they are doing so that those who are being observed will behave naturally. If the students who studied drinking habits had marched into those bars with camcorders and announced their intentions to the customers, the results might have been quite different.

Try a little naturalistic observation of your own. Go to a public place where people voluntarily seat themselves near others, such as a movie theater or a cafeteria with large tables. If you choose a setting where many people enter at once, you might recruit some friends to help you; you can divide the area into sections and give each observer one section to observe. As individuals and groups sit down, note how many seats they leave between themselves and the next person. On average, how far do people tend to sit from strangers? After you have your results, see how many possible explanations you can come up with.

Sometimes psychologists prefer to make observations in a laboratory setting. In laboratory observation, researchers have more control of the situation. They can use sophisticated equipment, determine the number of people who will be observed, maintain a clear line of vision, and so forth. Say you wanted to know how infants of different ages respond when left with a stranger. You might have parents and their infants come to your laboratory, observe them playing together for a while through a one-way window, then have a stranger enter the room and, a few minutes later, have the parent leave. You could record signs of distress in the children, interactions with the stranger, and other behavior. If you did this, you would find that very young infants carry on cheerfully with whatever they are doing when the parent leaves. However, by the age of about 8 months, many children will burst into tears or show other signs of what child psychologists call “separation anxiety.”

One shortcoming of laboratory observation is that the presence of researchers and special equipment may cause people to behave differently than they would in their usual surroundings. Furthermore, whether they are in natural or laboratory settings, observational studies, like other descriptive methods, are more useful for describing behavior than for explaining it. The barroom results we described do not necessarily mean that being in a group makes people drink a lot. People may join a group because they are already interested in drinking and find it more comfortable to hang around the bar if they are with others. Similarly, if we observe infants protesting whenever a parent leaves the room, is it because they have become attached to their parents and want them nearby, or have they simply learned from experience that crying brings an adult with a cookie and a cuddle? Observational studies alone cannot answer such questions.

Tests

Psychological tests, sometimes called assessment instruments, are procedures for measuring and evaluating personality traits, emotions, aptitudes, interests, abilities, and values. Typically, tests require people to answer a series of written or oral questions. The answers may then be totaled to yield a single numerical score, or a set of scores. Objective tests, also called inventories, measure beliefs, feelings, or behaviors of which an individual is aware; projective tests are designed to tap unconscious feelings or motives.

At one time or another, you no doubt have taken a personality test, an achievement test, or a vocational aptitude test. Hundreds of psychological tests are used in industry, education, the military, and the helping professions, and many tests are also used in research. Some tests are given to individuals, others to large groups. These measures help clarify differences among people, as well as differences in the reactions of the same person on different occasions or at different stages of life. Tests may be used to promote self-understanding, to evaluate psychological treatments and programs, or, in scientific research, to draw generalizations about human behavior. Well-constructed psychological tests are a great improvement over simple self-evaluation because many people have a distorted view of their own abilities and traits.

One test of a good test is whether it is standardized, having uniform procedures for giving and scoring the test. It would hardly be fair to give some people detailed instructions and plenty of time and others only vague instructions and limited time. Those who administer the test must know exactly how to explain the tasks involved, how much time to allow, and what materials to use. Scoring is usually done by referring to norms, or established standards of performance. The usual procedure for developing norms is to give the test to a large group of people who resemble those for whom the test is intended. Norms determine which scores can be considered high, low, or average.

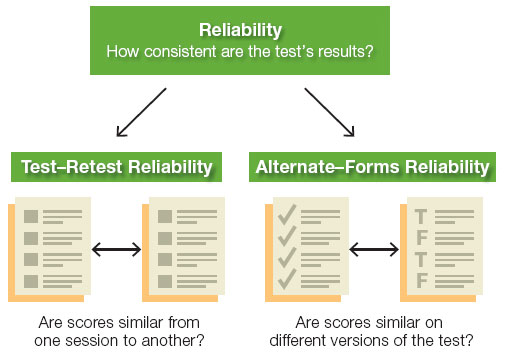

Test construction presents many challenges. For one thing, the test must have reliability, producing the same results from one time and place to the next or from one scorer to another. A vocational interest test is not reliable if it says that Tom would make a wonderful engineer but a poor journalist, but then gives different results when Tom retakes the test a week later. Psychologists can measure test–retest reliability by giving the test twice to the same group of people and comparing the two sets of scores statistically. If the test is reliable, individuals' scores will be similar from one session to another. This method has a drawback, however: People tend to do better the second time they take a test, after they have become familiar with it. A solution is to compute alternate-forms reliability by giving different versions of the same test to the same group on two separate occasions (see Figure2.3). The items on the two forms are similar in format but are not identical in content. Performance cannot improve because of familiarity with the items, although people may still do somewhat better the second time around because they have learned the procedures expected of them.

Figure2.3

Consistency in the Measurement Process

Psychological tests, like all forms of scientific measurement, need to have the property of reliability. This means that a measuring instrument measures the same way each time someone uses it.

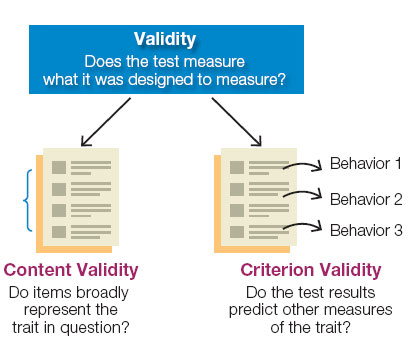

To be useful, a test must also have validity, measuring what it sets out to measure. A creativity test is not valid if what it actually measures is verbal sophistication. If the items broadly represent the trait in question, the test is said to have content validity. If you were testing, say, employees' job satisfaction, and your test tapped a broad array of relevant beliefs and behaviors (e.g., “Do you feel you have reached a dead end at work?”, “Are you bored with your assignments?”), it would have content validity. If the test asked only how workers felt about their salary level, it would lack content validity and would be of little use; after all, highly paid people are not always satisfied with their jobs, and people who earn low wages are not always dissatisfied.

Most tests are also judged on criterion validity, the ability to predict independent measures, or criteria, of the trait in question (see Figure2.4). The criterion for a scholastic aptitude test might be college grades; the criterion for a test of shyness might be behavior in social situations. To find out whether your job satisfaction test had criterion validity, you might return a year later to see whether it correctly predicted absenteeism, resignations, or requests for job transfers.

Figure2.4

Accuracy in the Measurement Process

Psychological tests, like all forms of scientific measurement, need to have the property of validity. This means that a measuring instrument actually measures what it was designed to measure.

Teachers, parents, and employers do not always stop to question a test's validity, especially when the results are summarized in a single, precise-sounding number, such as an IQ score of 115 or a job applicant's ranking of 5. Among psychologists and educators, however, controversy exists about the validity and usefulness of even some widely used tests, including mental tests like the Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT) and standardized IQ tests. A comprehensive review of the evidence from large studies and national samples concluded that mental tests do a good job of predicting intellectual performance (Sackett, Borneman, & Connelly, 2008). But not everyone has access to the opportunities that lead to strong test scores and strong real-world performance. Motivation, study skills, self-discipline, practical “smarts,” and other traits not measured by IQ or other mental tests are major influences on success in school and on the job.

Criticisms and reevaluations of psychological tests keep psychological assessment honest and scientifically rigorous. In contrast, the pop-psych tests found in magazines, newspapers, and on the Internet usually have not been evaluated for either validity or reliability. These questionnaires have inviting headlines, such as “Which Breed of Dog Do You Most Resemble?” or “The Seven Types of Lovers,” but they are merely lists of questions that someone thought sounded good.

A Sample Personality Test

Swinkels, A., & Giuliano, T. A. (1995). The measurement and conceptualization of mood awareness: Monitoring and labeling one's mood states. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 934-949.

Surveys

Everywhere you go, someone wants your opinion. Political polls want to know what you think of some candidate. Eat at a restaurant, get your car serviced, or stay at a hotel, and you'll get a satisfaction survey 5 minutes later. Online, readers and users of any product offer their rating. Whereas psychological tests usually generate information about people indirectly, surveys are questionnaires and interviews that gather information by asking people directly about their experiences, attitudes, or opinions. How reliable are all these surveys?

Surveys produce bushels of data, but they are not easy to do well. Sampling problems are often an issue. When a talk-radio host or TV personality invites people to send comments about a political matter, the results are not likely to generalize to the population as a whole, even if thousands of people respond. Why? As a group, people who listen to Rush Limbaugh are more conservative than fans of Jon Stewart. Popular polls and surveys (like the one about college women on spring break) also frequently suffer from a volunteer bias: People who are willing to volunteer their opinions may differ from those who decline to take part. When you read about a survey (or any other kind of study), always ask who participated. A nonrepresentative sample does not necessarily mean that a survey is worthless or uninteresting, but it does mean that the results may not hold true for other groups.

Yet another problem with surveys, and with self-reports in general, is that people sometimes lie, especially when the survey is about a touchy or embarrassing topic. (“What? Me do that disgusting/illegal/dishonest thing? Never!”) In studies comparing self-reports of illicit drug use with urinalysis results from the same individuals, between 30 and 70 percent of those who test positive for cocaine or opiates deny having used drugs recently (Tourangeau & Yan, 2007). The likelihood of lying is reduced when respondents are guaranteed anonymity and allowed to respond in private. Researchers can also check for lying by asking the same question several times with different wording to see whether the answers are consistent. But not all surveys use these techniques, and even when respondents are trying to be truthful, they may misinterpret the survey questions, hold inaccurate perceptions of their own behavior, or misremember the past.

When you hear about the results of a survey or opinion poll, you also need to consider which questions were (and were not) asked and how the questions were phrased. These aspects of a survey's design may reflect assumptions about the topic or encourage certain responses—as political pollsters well know. Many years ago, famed sex researcher Alfred Kinsey, in his pioneering surveys of sexual behavior, made it his practice always to ask, “How many times have you (masturbated, had nonmarital sex, etc.)?” rather than “Have you ever (masturbated, had nonmarital sex, etc.)?” (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948; Kinsey et al., 1953). The first way of phrasing the question tended to elicit more truthful responses than the second because it removed the respondent's self-consciousness about having done any of these things. The second way of phrasing the question would have permitted embarrassed respondents to reply with a simple but dishonest “no.”

Technology can help researchers overcome some of the problems inherent in conducting surveys. Because many people feel more anonymous when they answer questions on a computer than when they complete a paper-and-pencil questionnaire, computerized questionnaires can reduce lying (Turner et al., 1998). Participants are usually volunteers and are not randomly selected, but because Web-based samples are often huge, consisting of hundreds of thousands of respondents, they are more diverse than traditional samples in terms of gender, socioeconomic status, geographic region, and age. In these respects, they tend to be more representative of the general population than traditional samples are (Gosling et al., 2004). Even when people from a particular group make up only a small proportion of the respondents, in absolute numbers, they may be numerous enough to provide useful information about that group. Whereas a typical sample of 1,000 representative Americans might include only a handful of Buddhists, a huge Internet sample might draw hundreds.

Internet surveys also carry certain risks, however. It is hard for researchers to know whether participants understand the instructions and the questions and are taking them seriously. Also, many tests and surveys on the Web have never been validated, which is why drawing conclusions from them about your personality or mental adjustment could be dangerous to your mental health! Always check the credentials of those designing the test or survey and be sure it is not just something someone made up at his or her computer in the middle of the night.