2.6 Keeping the Enterprise Ethical

Because rigorous research methods are the very heart of science, psychologists spend considerable time discussing and debating their procedures for collecting and evaluating data. And they are also concerned about the ethical principles governing research and practice. In colleges and universities, a review committee must approve all studies and be sure they conform to federal regulations. In addition, the American Psychological Association (APA) has a code of ethics that all members must follow. Even people who are not members of the APA, whether working in the United States or around the world, often follow the code in their research. The code of ethics is subject to frequent reexamination.

The Ethics of Studying Human Beings

The APA code calls on psychological scientists to respect the dignity and welfare of the people they study. Participants must enter a study voluntarily and must know enough about it to make an intelligent decision about taking part, a doctrine known as informed consent. Researchers must also protect participants from physical and mental harm, and if any risk exists, they must warn them in advance and give them an opportunity to withdraw at any time.

The policy of informed consent sometimes clashes with an experimenter's need to disguise the true purpose of the study. In such cases, if the purpose were revealed in advance, the results would be ruined because the participants would not behave naturally. In social psychology especially, a study's design sometimes calls for an elaborate deception. For example, a confederate of the researcher might pretend to be having a seizure. The researcher can then find out whether bystanders—the uninformed participants—will respond to a person needing help. If the participants knew that the confederate was only acting, they would obviously not bother to intervene or call for assistance.

Sometimes people have been misled about procedures that are intentionally designed to make them angry, guilty, ashamed, or anxious so that researchers can learn what people do when they feel this way. In studies of embarrassment and anger, people have been made to look clumsy in front of others, have been called insulting names, or have been told they were incompetent. In studies of dishonesty, participants have been entrapped into cheating and have then been confronted with evidence of their guilt. The APA code requires that participants be thoroughly debriefed when the study is over and told why deception was necessary. In addition to debriefing, the APA's ethical guidelines require researchers to show that any deception is justified by a study's potential value and to consider alternative procedures.

The Ethics of Studying Animals

Ethical issues also arise in animal research. Animals are used in only a small percentage of psychological studies, but they play a crucial role in some areas. Usually they are not harmed (as in research on mating in hamsters, which is definitely fun for the hamsters), but sometimes they are (as when rats brought up in deprived or enriched environments are sacrificed so that their brains can be examined for any effects). Psychologists study animals for many reasons:

To conduct basic research on a particular species. For example, researchers have learned a great deal about the unusually lusty and cooperative lives of bonobo apes.

To discover practical applications. For example, behavioral studies have shown farmers how to reduce crop destruction by birds and deer without resorting to their traditional method—shooting the animals.

To clarify theoretical questions. For example, we might not attribute the longer lifespans of women solely to lifestyle factors and health practices if we discover that a male–female difference exists in other mammals as well.

To improve human welfare. For example, animal studies have helped researchers develop ways to reduce chronic pain, rehabilitate patients with neurological disorders, and understand the mechanisms underlying memory loss and senility.

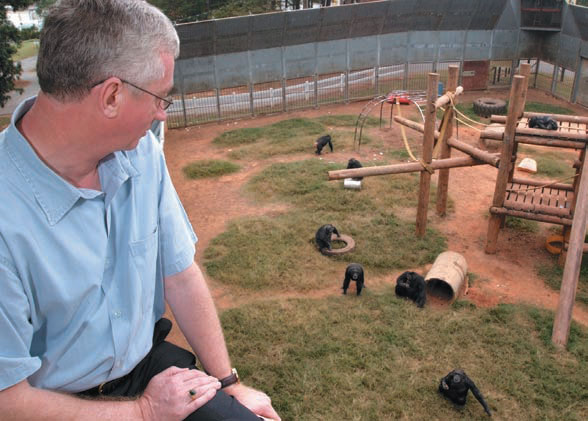

Psychologists sometimes use animals to study learning, memory, emotion, and social behavior. Here, Frans de Waal observes a group of chimpanzees socializing in an outdoor play area.

In recent decades, some psychological and medical scientists have been trying to find ways to do their research without using animals at all, by using computer simulations or other new technologies. When animals are essential to research, the APA's ethical code includes comprehensive guidelines to ensure their humane treatment. Federal laws governing the housing and care of research animals—particularly our closest relatives, the great apes—are stronger than they used to be; no future research can be done on apes unless it is vital to human welfare and cannot be conducted with other methods. Moreover, thanks to a growing understanding of animals' instinctive, social, and cognitive needs—even in so-called “lower” species like the lab rat—many psychological scientists have changed the way they treat them, which improves their research as well as the animals' well-being (Patterson-Kane, Harper, & Hunt, 2001). The difficult task for scientists is to balance the benefits of animal research with an acknowledgment of past abuses and a compassionate concern for the welfare of species other than our own.

Now you are ready to explore more deeply what psychologists have learned about human psychology. The methods of psychological science, as we will see repeatedly in the remainder of the book, have overturned some deeply entrenched assumptions about the way people think, feel, act, and adapt, and have yielded information that greatly improves human well-being. These methods illuminate our human errors and biases and enable us to seek knowledge with an open mind. Biologist Thomas Huxley put it beautifully. The essence of science, he said, is “to sit down before fact as a little child, be prepared to give up every preconceived notion, follow humbly wherever and to whatever abyss nature leads, or you shall learn nothing.”