5.3

Exploring the Dream World

Every culture has its theories about dreams. In some cultures, dreams are believed to occur when the spirit leaves the body to wander the world or speak to the gods. In others, dreams are thought to reveal the future. A Chinese Taoist of the third century b.c. pondered the possible reality of the dream world. He told of dreaming that he was a butterfly flitting about. “Suddenly I woke up and I was indeed Chuang Tzu. Did Chuang Tzu dream he was a butterfly, or did the butterfly dream he was Chuang Tzu?”

For years, researchers believed that everyone dreams, and indeed most people who claim they never have dreams will report them if they are awakened during REM sleep. However, as we noted earlier, a few rare individuals apparently do not dream at all (Pagel, 2003; Solms, 1997). Most but not all of them have suffered some brain injury. In this section, we will explore the dream world, beginning with explanations of why people dream.

Explanations of Dreaming

In dreaming, the focus of attention is inward, though occasionally an external event, such as a wailing siren, can influence the dream's content. While a dream is in progress, it may be vivid or vague, terrifying or peaceful. It may also seem to make perfect sense—until you wake up and recall it as illogical, bizarre, and disjointed. Although most of us are unaware of our bodies or where we are while we are dreaming, some people say that they occasionally have lucid dreams, in which they know they are dreaming and feel as though they are conscious (LaBerge, 2014). A few even claim that they can control the action in these dreams, much as a scriptwriter decides what will happen in a movie.

Why do the images in dreams arise at all? Why doesn't the brain just rest, switching off all thoughts and images and launching us into a coma? Why, instead, do we spend our nights taking a chemistry exam, reliving an old love affair, flying through the air, or fleeing from dangerous strangers or animals in the fantasy world of our dreams?

In popular culture, many people still hold to Freudian psychoanalytic notions of dreaming. Freud (1900/1953) claimed that dreams are “the royal road to the unconscious” because our dreams reflect unconscious conflicts and wishes, often sexual or violent in nature. The thoughts and objects in these dreams, he said, are disguised symbolically to make them less threatening: Your father might appear as your brother, a penis might be disguised as a snake or a cigar, or intercourse with a forbidden partner might be expressed as a train entering a tunnel.

Most psychologists today accept Freud's notion that dreams are more than incoherent ramblings of the mind and that they can have psychological meaning, but they also consider psychoanalytic interpretations of dreams to be far-fetched. No reliable rules exist for interpreting the unconscious meaning of dreams, and there is no objective way to know whether a particular interpretation is correct. Nor is there any convincing empirical support for most of Freud's claims. Psychoanalytic interpretations are common in popular books and on the Internet, but they are only the writers' personal hunches. Even Freud warned against simplified, “this symbol means that” interpretations; each dream, said Freud, must be analyzed in the context of the dreamer's waking life. Not everything in a dream is symbolic; sometimes, he cautioned, “A cigar is only a cigar.”Let's examine some explanations for why we dream.

Dreams as Efforts to Deal with Problems One modern explanation of dreams holds that they reflect the ongoing conscious preoccupations of waking life, such as concerns over relationships, work, sex, or health (Cartwright, 1977; Hall, 1953a, 1953b). In this problem-focused approach to dreaming, the symbols and metaphors in a dream do not disguise its true meaning; they convey it. Psychologist Gayle Delaney once told of a woman who dreamed she was swimming underwater. The woman's 8-year-old son was on her back, his head above the water. Her husband was supposed to take a picture of them, but for some reason he wasn't doing it, and she was starting to feel as if she were going to drown. To Delaney, the message was obvious: The woman was “drowning” under the responsibilities of childcare and her husband wasn't “getting the picture” (in Dolnick, 1990).

The problem-focused explanation of dreaming is supported by findings that dreams are more likely to contain material related to a person's current concerns than chance would predict (Domhoff, 1996). Among college students, who are often worried about grades and tests, test-anxiety dreams are common: The dreamer is unprepared for or unable to finish an exam, or shows up for the wrong exam, or can't find the room where the exam is being given. Traumatic experiences can also affect people's dreams. In a cross-cultural study in which children kept dream diaries for a week, Palestinian children living in neighborhoods under threat of violence reported more themes of persecution and violence than did Finnish or Palestinian children living in peaceful environments (Punamaeki & Joustie, 1998).

Some psychologists believe that dreams not only reflect our waking concerns but also provide us with an opportunity to resolve them. According to Rosalind Cartwright (2010), in people suffering from the grief of divorce, recovery is related to a particular pattern of dreaming: The first dream of the night often comes sooner than it ordinarily would, lasts longer, and is more emotional and story-like. Depressed people's dreams tend to become less negative and more positive as the night wears on, and this pattern, too, predicts recovery (Cartwright et al., 1998). Cartwright concluded that getting through a crisis or a rough period in life takes “time, good friends, good genes, good luck, and a good dream system.”

Dreams as Thinking Like the problem-focused approach, the cognitive approach to dreaming emphasizes current concerns, but it makes no claims about problem solving during sleep. In this view, dreaming is simply a modification of the cognitive activity that goes on when we are awake. In dreams, we construct reasonable simulations of the real world, drawing on the same kinds of memories, knowledge, metaphors, and assumptions about the world that we do when we are not sleeping (Antrobus, 1991, 2000; Foulkes & Domhoff, 2014). Thus, the content of our dreams may include thoughts, concepts, and scenarios that may or may not be related to our daily problems. We are most likely to dream about our families, friends, studies, jobs, worries, or recreational interests—topics that also occupy our waking thoughts.

Recording the Intangible

In the cognitive view, the brain is doing the same kind of work during dreams as it does when we are awake; indeed, parts of the cerebral cortex involved in perceptual and cognitive processing during the waking hours are highly active during dreaming. The difference is that when we are asleep we are cut off from sensory input and feedback from the world and our bodily movements; the only input to the brain is its own output. Therefore, our dreaming thoughts tend to be more unfocused and diffuse than our waking ones—unless we're daydreaming. Our brains show similar patterns of activity when we are night dreaming as when we are daydreaming—a finding that suggests that nighttime dreaming, like daydreaming, might be a mechanism for simulating events that we think (or fear) might occur in the future (Domhoff, 2011).

The cognitive view predicts that if a person could be totally cut off from all external stimulation while awake, mental activity would be much like that during dreaming, with the same hallucinatory quality.The cognitive approach also predicts that as cognitive abilities and brain connections mature during childhood, dreams should change in nature, and they do. Toddlers may not dream at all in the sense that adults do. And although young children may experience visual images during sleep, their cognitive limitations keep them from creating true narratives until age 7 or 8 (Foulkes, 1999). Their dreams are infrequent and tend to be bland and static, and are often about everyday things (“I saw a dog; I was sitting”). But as they grow up, their dreams gradually become more and more intricate and story-like.

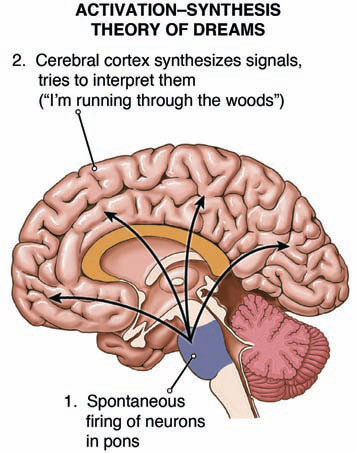

Dreams as Interpreted Brain Activity A third modern approach to dreaming, the activation–synthesis theory, draws heavily on physiological research and aims to explain not why you might dream about a test when you are about to take one, but why you might dream about being a cat that turns into a hippo that plays in a rock band. Often dreams just don't make sense; indeed, most are bizarre, illogical, or both. According to the activation–synthesis explanation, first proposed by psychiatrist J. Allan Hobson (1988, 1990), these dreams are not “children of an idle brain,” as Shakespeare called them. They are largely the result of neurons firing spontaneously in the pons (in the lower part of the brain) during REM sleep. These neurons control eye movement, gaze, balance, and posture, and they send messages to sensory and motor areas of the cortex responsible during wakefulness for visual processing and voluntary action.

According to this view, the signals originating in the pons have no psychological meaning in themselves. But the cortex tries to make sense of them by synthesizing, or integrating, them with existing knowledge and memories to produce some sort of coherent interpretation. This is just what the cortex does when signals come from sense organs during ordinary wakefulness. The idea that one part of the brain interprets what has gone on in other parts, whether you are awake or asleep, is consistent with many modern theories of how the brain works.

When neurons fire in the part of the brain that handles balance, for instance, the cortex may generate a dream about falling. When signals occur that would ordinarily produce running, the cortex may manufacture a dream about being chased. Because the signals from the pons occur randomly, the cortex's interpretation—the dream—is likely to be incoherent and confusing. And because the cortical neurons that control the initial storage of new memories are turned off during sleep, we typically forget our dreams upon waking unless we write them down or immediately recount them to someone else.

Since Hobson's original formulation, he and his colleagues have refined and modified this theory (Hobson, Pace-Schott, & Stickgold, 2000; Hobson et al., 2011; Tranquillo, 2014). The brain stem, they say, sets off responses in emotional and visual parts of the brain. At the same time, brain regions that handle logical thought and sensations from the external world shut down. These changes could further account for the fact that dreams are often emotionally charged, hallucinatory, and illogical.

In sum, in this view, wishes do not cause dreams; brain mechanisms do. Dream content, says Hobson (2002), may be “as much dross as gold, as much cognitive trash as treasure, and as much informational noise as a signal of something.” But that does not mean dreams are always meaningless. Hobson (1988) has argued that the brain “is so inexorably bent upon the quest for meaning that it attributes and even creates meaning when there is little or none to be found in the data it is asked to process.” By studying these attributed meanings, you can learn about your unique perceptions, conflicts, and concerns—not by trying to dig below the surface of the dream, as Freud would, but by examining the surface itself. Or you can relax and enjoy the nightly entertainment that dreams provide.

Evaluating Dream Theories

How are we to evaluate these attempts to explain dreaming? All three modern approaches account for some of the evidence, but each one also has its drawbacks.

Are dreams a way to solve problems? It seems pretty clear that some dreams are related to current worries and concerns, but skeptics doubt that people can actually solve problems or resolve conflicts while sound asleep (Blagrove, 1996; Squier & Domhoff, 1998). Dreams, they say, merely give expression to our problems. The insights into those problems that people attribute to dreaming could be occurring after they wake up and have a chance to think about what is troubling them.

The activation–synthesis theory has also come in for criticism (Domhoff, 2003). Not all dreams are as disjointed or as bizarre as the theory predicts; in fact, many tell a coherent, if fanciful, story. Moreover, the activation–synthesis approach does not account well for dreaming that goes on outside of REM sleep. Some neuropsychologists emphasize different brain mechanisms involved in dreams, and many believe that dreams do reflect a person's goals and desires.

Finally, the cognitive approach to dreams is promising, but some of its claims remain to be tested against neurological and cognitive evidence. At present, however, it is a leading contender because it incorporates many elements of other theories and fits what we currently know about waking cognition and cognitive development.

Perhaps it will turn out that different kinds of dreams have different purposes and origins. We all know from experience that some of our dreams seem to be related to daily problems, some are vague and incoherent, and some are anxiety dreams that occur when we are worried or depressed. But whatever the source of the images in our sleeping brains may be, we need to be cautious about interpreting our own dreams or anyone else's. A study of people in India, South Korea, and the United States showed that individuals are biased and self-serving in their dream interpretations, accepting those that fit in with their preexisting beliefs or needs, and rejecting those that do not. For example, they will give more weight to a dream in which God commands them to take a year off to travel the world than one in which God commands them to take a year off to work in a leper colony. And they are more likely to see meaning in a dream in which a friend protects them from attackers than one in which their romantic partner is caught kissing that same friend (Morewedge & Norton, 2009). Our biased interpretations may tell us more about ourselves than do our actual dreams.