5.4

The Riddle of Hypnosis

For many years, stage hypnotists, “past-lives channelers,” and some psychotherapists have been reporting that they can “age-regress” hypnotized people to earlier years or even earlier centuries. Some therapists claim that hypnosis helps their patients accurately retrieve long-buried memories, and a few even claim that hypnosis has helped their patients recall alleged abductions by extraterrestrials. What are we to make of all this? Because hypnosis has been used for everything from parlor tricks and stage shows to medical and psychological treatments, it is important to understand just what this procedure can and cannot achieve. In this section, we will begin with a general look at the major findings on hypnosis; then we will consider two leading explanations of hypnotic effects. But first, take this short quiz to see how much you know about hypnosis.

Hypnosis Quiz

The Nature of Hypnosis

Hypnosis is a procedure in which a practitioner suggests changes in the sensations, perceptions, thoughts, feelings, or behavior of the subject (Lynn & Kirsch, 2015). The hypnotized person, in turn, tries to alter his or her cognitive processes in accordance with the hypnotist's suggestions (Nash & Nadon, 1997). Hypnotic suggestions typically involve performance of an action (“Your arm will slowly rise”), an inability to perform an act (“You will be unable to bend your arm”), or a distortion of normal perception or memory (“You will feel no pain,” “You will forget being hypnotized until I give you a signal”). People usually report that their response to a suggestion feels involuntary, as if it happened without their willing it. Learn more about the scientific basis of hypnosis by watching the video The Uses and Limitations of Hypnosis 1.

Watch

The Uses and Limitations of Hypnosis 1

To induce hypnosis, the hypnotist typically suggests that the person being hypnotized feels relaxed, is getting sleepy, and feels the eyelids getting heavier and heavier. In a singsong or monotonous voice, the hypnotist assures the subject that he or she is sinking “deeper and deeper.” Sometimes the hypnotist has the person concentrate on a color or a small object, or on certain bodily sensations. People who have been hypnotized report that the focus of attention turns outward, toward the hypnotist's voice. They sometimes compare the experience to being totally absorbed in a good movie or favorite piece of music. The hypnotized person almost always remains fully aware of what is happening and remembers the experience later unless explicitly instructed to forget it. Even then, the memory can be restored by a prearranged signal.

Since the late 1960s, thousands of articles on hypnosis have appeared. Based on controlled laboratory and clinical studies, most psychological scientists agree that hypnosis is not a mystical trance or strange state of consciousness. Indeed, some worry that thinking of hypnosis in those ways, as a kind of dark art, has interfered with our understanding of it (Posner & Rothbart, 2011). Although scientists disagree about what exactly hypnosis is, they generally agree on the following points (Kirsch & Lynn, 1995; Nash, 2001; Nash & Nadon, 1997):

Hypnotic responsiveness depends more on the efforts and qualities of the person being hypnotized than on the skill of the hypnotist. Some people are more responsive to hypnosis than others, but why they are is unknown (Barnier, Cox, & McConkey, 2014). Surprisingly, such susceptibility is unrelated to general personality traits such as gullibility, trust, submissiveness, or conformity (Nash & Nadon, 1997). And it is only weakly related to the ability to become easily absorbed in activities and the world of imagination (Council, Kirsch, & Grant, 1996; Green & Lynn, 2010; Nash & Nadon, 1997).

Hypnotized people cannot be forced to do things against their will. Like drunkenness, hypnosis can be used to justify letting go of inhibitions (“I know this looks silly, but after all, I'm hypnotized”). Hypnotized individuals may even comply with a suggestion to do something that looks embarrassing or dangerous. But the person is choosing to turn responsibility over to the hypnotist and to cooperate with the hypnotist's suggestions (Lynn, Rhue, & Weekes, 1990). Hypnotized people will not do anything that actually violates their morals or constitutes a real danger to themselves or others.

Feats performed under hypnosis can be performed by motivated people without hypnosis. Hypnotized subjects sometimes perform what seem like extraordinary mental or physical feats, but hypnosis does not actually enable people to do things that would otherwise be impossible. With proper motivation, support, and encouragement, the same people could do the same things even without being hypnotized (Chaves, 1989; Spanos, Stenstrom, & Johnson, 1988).

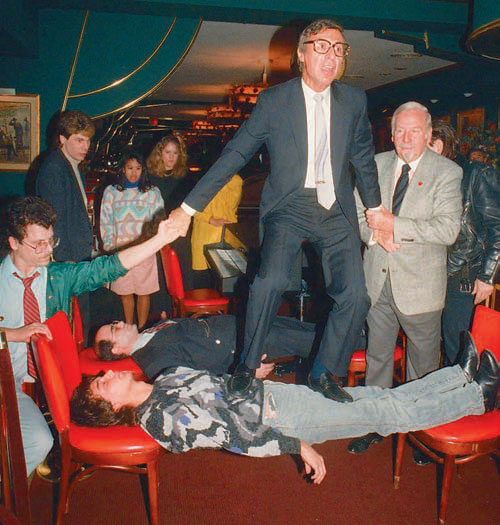

Is it hypnosis that enables the man stretched out between two chairs to hold the weight of the man standing on him, without flinching? This audience assumes so, but the only way to find out whether hypnosis produces unique abilities is to do research with control groups. It turns out that people can do the same thing even when they are not hypnotized.

Hypnosis does not increase the accuracy of memory. In rare cases, hypnosis has been used successfully to jog the memories of crime victims, but usually the memories of hypnotized witnesses have been completely mistaken. Although hypnosis does sometimes boost the amount of information recalled, it also increases errors, perhaps because hypnotized people are more willing than others to guess, or because they mistake vividly imagined possibilities for actual memories (Dinges et al., 1992; Kihlstrom, 1994). Because pseudomemories and errors are so common in hypnotically induced recall, many scientific societies around the world oppose the use of “hypnotically refreshed” testimony in courts of law. The video The Uses and Limitations of Hypnosis 2 shows you more about the legitimate uses of hypnosis.

Watch

The Uses and Limitations of Hypnosis 2

Hypnosis does not produce a literal re-experiencing of long-ago events. Many people believe that hypnosis can be used to recover memories from as far back as birth. When one clinical psychologist who uses hypnosis in his own practice surveyed over 800 marriage and family therapists, he was dismayed to find that more than half agreed with this common belief (Yapko, 1994). But it is just plain wrong. When people are regressed to an earlier age, their mental and moral performance remains adultlike (Nash, 1987). Their brain-wave patterns and reflexes do not become childish; they do not reason as children do or show child-sized IQs. They may use baby talk or report that they feel 4 years old again, but the reason is not that they are actually reliving the experience of being 4; they are just willing to play the role.

Hypnotic suggestions have been used effectively for many medical and psychological purposes. Although hypnosis is not of much use for finding out what happened in the past, it can be useful in the treatment of psychological and medical problems. Its greatest success is in pain management; some people experience dramatic relief of pain resulting from conditions as diverse as burns, cancer, and childbirth, and others have learned to cope better emotionally with chronic pain. Hypnotic suggestions have also been used in the treatment of stress, anxiety, obesity, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome, chemotherapy-induced nausea, and even skin disorders (Nash & Barnier, 2007; Patterson & Jensen, 2003).

Theories of Hypnosis

Over the years, people have proposed many explanations of what hypnosis is and how it produces its effects. Today, two competing theories predominate.

Dissociation Theories One leading approach was originally proposed by Ernest Hilgard (1977, 1986), who argued that hypnosis, like lucid dreaming and even simple distraction, involves dissociation, a split in consciousness in which one part of the mind operates independently of the rest of consciousness. In many hypnotized people, said Hilgard, most of the mind is subject to hypnotic suggestion, but one part is a hidden observer, watching but not participating. Unless given special instructions, the hypnotized part remains unaware of the observer.

Hilgard attempted to question the hidden observer directly. In one procedure, hypnotized volunteers had to submerge an arm in ice water for several seconds, an experience that is normally excruciating. They were told that they would feel no pain, but that the unsubmerged hand would be able to signal the level of any hidden pain by pressing a key. In this situation, many people said they felt little or no pain—yet at the same time, their free hand was busily pressing the key. After the session, these people continued to insist that they had been pain-free unless the hypnotist asked the hidden observer to issue a separate report.

Ernest Hilgard, a pioneer in hypnosis research, discovered that when hypnotized people are told the pain will be minimal, they report little or no discomfort and seem unperturbed. Hypnosis has subsequently been used effectively for many medical purposes.

A contemporary version of this theory holds that during hypnosis, a dissociation occurs between two systems in the brain: the system that processes incoming information about the world, and an “executive” system that controls how we use that information. In hypnosis, the executive system turns off and hands its function over to the hypnotist. That leaves the hypnotist able to suggest how we should interpret the world and act in it (Woody & Bowers, 1994; Woody & Sadler, 2012) (see Figure5.5).

Figure5.5

The Dissociation Theory of Hypnosis

The Sociocognitive Approach The second major approach to hypnosis, the sociocognitive explanation, holds that the effects of hypnosis result from an interaction between the social influence of the hypnotist (the “socio” part) and the abilities, beliefs, and expectations of the subject (the “cognitive” part) (see Figure5.6) (Kirsch, 1997; Sarbin, 1991; Spanos, 1991). The hypnotized person is basically enacting a role. This role has analogies in ordinary life, where we willingly submit to the suggestions of parents, teachers, doctors, therapists, and television commercials. In this view, even the “hidden observer” is simply a reaction to the social demands of the situation and the suggestions of the hypnotist (Lynn & Green, 2011).

Figure5.6

The Sociocognitive Theory of Hypnosis

The hypnotized person is not merely faking or playacting, however. A person who has been instructed to fool an observer by faking a hypnotic state will tend to overplay the role and will stop playing it as soon as the other person leaves the room. In contrast, hypnotized subjects continue to follow the hypnotic suggestions even when they think they are not being watched (Kirsch et al., 1989; Spanos et al., 1993). Like many social roles, the role of “hypnotized person” is so engrossing and involving that actions required by the role may occur without the person's conscious intent.

Sociocognitive views explain why some people under hypnosis have reported spirit possession or “memories” of alien abductions (Clancy, 2005; Spanos, 1996). Suppose a young woman goes to a therapist or hypnotist seeking an explanation for her loneliness, unhappiness, nightmares, puzzling symptoms (such as waking up in the middle of the night in a cold sweat), or the waking dreams we described earlier. A therapist who already believes in alien abduction may use hypnosis, along with subtle and not-so-subtle cues about UFOs, to shape the way the client interprets her symptoms.

The sociocognitive view can also explain apparent cases of past-life regression. In a fascinating program of research, Nicholas Spanos and his colleagues (1991) directed hypnotized Canadian university students to regress past their own births to previous lives. About a third of the students (who already believed in reincarnation) reported being able to do so. But when they were asked, while supposedly reliving a past life, to name the leader of their country, say whether the country was at peace or at war, or describe the money used in their community, the students could not do it. (One young man, who thought he was Julius Caesar, said the year was 50 a.d. and he was emperor of Rome. But Caesar died in 44 b.c. and was never crowned emperor, and dating years as a.d. or b.c. did not begin until several centuries later.) Not knowing anything about the language, dates, customs, and events of their “previous life” did not deter the students from constructing a story about it, however. They tried to fulfill the requirements of the role by weaving events, places, and people from their present lives into their accounts, and by picking up cues from the experimenter.

The researchers concluded that the act of “remembering” another self involves the construction of a fantasy that accords with the rememberer's own beliefs and also the beliefs of others—in this case, those of the authoritative hypnotist.