Chapter 6Sensation and Perception

Learning Objectives

LO 6.1.B Differentiate between absolute thresholds, difference thresholds, and signal detection.

LO 6.1.D Describe how selective attention and inattentional blindness are related.

LO 6.2.C Summarize the evidence indicating that the visual system is not simply a “camera.”

LO 6.4.B Describe the basic pathway from smell receptors to the cerebral cortex.

LO 6.4.C List the four basic skin senses that humans perceive.

LO 6.4.E Discuss the two senses that allow us to monitor our internal environment.

LO 6.5.B Discuss four psychological factors that influence how we perceive the world.

LO 6.5.C Summarize the evidence both for and against subliminal perception.

Ask questions . . . be willing to wonder

Why do some people see religious images in a tortilla or a grilled cheese sandwich?

Why does having a cold make it harder to taste the flavor of food?

Why does pain sometimes persist long after the reason for it is gone?

Can subliminal messages affect what you buy and believe?

A college student in Missouri reports spotting three triangular “UFOs” hovering over the highway during rush hour. An Australian man sees an image of Jesus burned into the surface of an ashtray. A photograph published shortly after September 11, 2001, appears to show a sinister face in smoke billowing from the doomed World Trade Center, which some people interpret as Osama bin Laden's.

We have all heard reports like these. Some of us scoff at them; others take them seriously. Are UFOs, visions of faces in everyday objects, and other strange sightings reported only by gullible people, or do smart, savvy people see them too? If such experiences are illusions, then why are they so frequent and so detailed, and why are those who have them so confident that what they saw was real?

In this chapter, we will try to answer these questions by exploring how our senses take in information from the environment and how our brains use this information to construct a model of the world. We will focus on two closely connected sets of processes that enable us to know what is happening both inside our bodies and in the world beyond our own skins. The first, sensation, produces an immediate awareness of sound, color, form, and other building blocks of consciousness. Without sensation, we would lose touch with reality. But to make sense of the world impinging on our senses, we also need perception to organize sensory information into meaningful patterns.

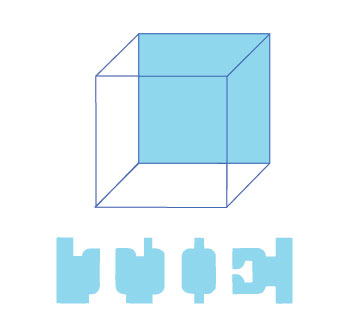

If you stare at the cube, the surface on the outside and front will suddenly be on the inside and back, or vice versa, because your brain can interpret the sensory image in two different ways. The other blue-and-white drawing can also be perceived in two ways. Do you see them?

As an example of how the processes of sensation and perception are separable yet intertwined, consider an unusual condition called prosopagnosia. People with this disorder have an inability to perceive faces, due to deficits in a specific area of the brain called the fusiform gyrus. Their eyes work just fine; there's no problem with sensing visual information in the world. But their ability to perceive those sensory impulses as a human face is compromised. Although sensation and perception usually “feel” to us like one seamless process, we learn in this chapter that they can be distinguished by where and how they occur, and by disruptions that might affect one process but not the other.

Sensation and perception are the foundation for learning, thinking, and acting. Findings about these processes can also be put to practical use, as in the design of industrial robots and in the training of pilots who must make crucial decisions based on what they sense and perceive. In addition, an understanding of sensation and perception helps us think more critically about our own experiences, and encourages in us a certain humility: Usually we are sure that what we sense and perceive must be true, yet sometimes we are just plain wrong.