6.2

Vision

Because we evolved to be most active in the daytime, we are equipped to take advantage of the sun's illumination. More information about the external world comes to us through our eyes than through any other sense organ. Get ready for an eye-opening look at how the process of vision works.

What We See

The stimulus for vision is light; even cats, raccoons, and other creatures famous for their ability to get around in the dark need some light to see. Visible light comes from the sun and other stars and from lightbulbs, and it is also reflected off objects. The physical characteristics of light affect three psychological dimensions of our visual world: hue, brightness, and saturation (see Figure6.3):

Hue, the dimension of visual experience specified by color names, is related to the wavelength of light—that is, to the distance between the crests of a light wave. Shorter waves tend to be seen as violet and blue, longer ones as orange and red. The sun produces white light, which is a mixture of all the visible wavelengths. Sometimes, drops of moisture in the air act like a prism: They separate the sun's white light into the colors of the visible spectrum, and we are treated to a rainbow.

Brightness is the dimension of visual experience related to the amount, or intensity, of the light an object emits or reflects, and corresponds to the amplitude (maximum height) of the light wave. Generally, the more light an object reflects, the brighter it appears. However, brightness is also affected by wavelength: Yellows appear brighter than reds and blues even when their physical intensities are equal.

Saturation (colorfulness) is the dimension of visual experience related to the complexity of light—that is, to how wide or narrow the range of wavelengths is. When light contains only a single wavelength, it is said to be pure, and the resulting color is completely saturated. White light, in contrast, contains all the wavelengths of visible light (corresponding to all the colors in the visible spectrum) and has zero saturation. Black is a lack of any light at all (has no color), and so is also completely unsaturated. In nature, pure light is extremely rare. We usually sense a mixture of wavelengths, and as a result we see colors that are duller and paler than completely saturated ones.

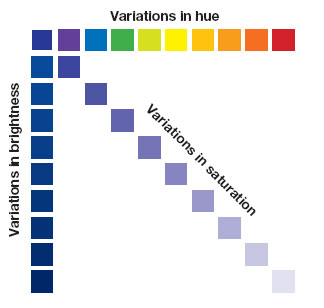

Figure 6.3

Psychological Dimensions of the Visual World

Variations in brightness, hue, and saturation represent psychological dimensions of vision that correspond to the intensity, wavelength, and complexity of wavelengths of light.

An Eye on the World

Light enters the visual system through the eye, a wonderfully complex and delicate structure. As you read this section, examine Figure6.4. Notice that the front part of the eye is covered by the transparent cornea. The cornea protects the eye and bends incoming light rays toward a lens located behind it. A camera lens focuses incoming light by moving closer to or farther from the shutter opening. However, the lens of the eye works by subtly changing its shape, becoming more or less curved to focus light from objects that are close by or far away. The amount of light that gets into the eye is controlled by muscles in the iris, the part of the eye that gives it color. The iris surrounds the round opening, or pupil, of the eye. When you enter a dim room, the pupil widens, or dilates, to let more light in. When you emerge into bright sunlight, the pupil gets smaller, contracting to allow in less light.

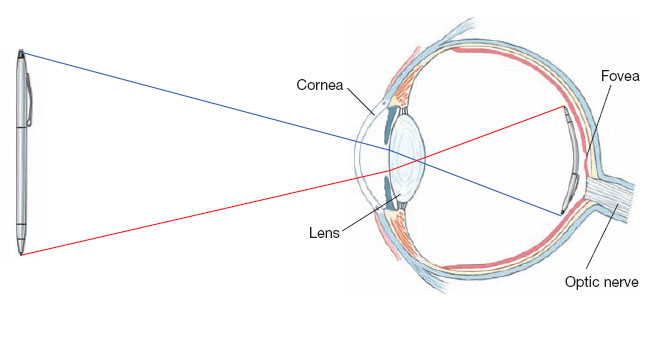

Figure 6.4

Major Structures of the Eye

The visual receptors are located in the back of the eye, or retina. In a developing embryo, the retina forms from tissue that projects out from the brain, not from tissue destined to form other parts of the eye; thus, the retina is actually an extension of the brain. As Figure6.5 shows, when the lens of the eye focuses light on the retina, the result is an upside-down image, just as it is with any optical device. Light from the top of the visual field stimulates light-sensitive receptor cells in the bottom part of the retina, and vice versa. The brain interprets this upside-down pattern of stimulation as something that is right-side up.

Figure 6.5

The Retinal Image

When we look at an object, the light pattern on the retina is upside down. René Descartes was probably the first person to demonstrate this fact. He cut a piece from the back of an ox’s eye and replaced the piece with paper. When he held the eye up to the light, he saw an upside-down image of the room on the paper. You could take any ordinary lens and get the same result.

About 120 to 125 million receptors in the retina are long and narrow, and are called rods. Another 7 or 8 million receptors are cone shaped, and are called, appropriately, cones. The center of the retina, or fovea, where vision is sharpest, contains only cones, clustered densely together. From the center to the periphery, the ratio of rods to cones increases, and the outer edges contain virtually no cones.

Rods are more sensitive to light than cones and thus enable us to see even in dim light. (Cats see well in dim light in part because they have a high proportion of rods.) Because rods occupy the outer edges of the retina, they also handle peripheral (side) vision. But rods cannot distinguish different wavelengths of light so they are not sensitive to color, which is why it is often hard to distinguish colors clearly in dim light. To see colors, we need cones, which come in three classes that are sensitive to specific wavelengths of light. But cones need much more light than rods do to respond, so they don't help us much when we are trying to find a seat in a darkened movie theater.

We have all noticed that it takes time for our eyes to adjust fully to dim illumination. This process of dark adaptation involves chemical changes in the rods and cones. The cones adapt quickly, within 10 minutes or so, but they never become very sensitive to the dim illumination. The rods adapt more slowly, taking 20 minutes or longer, but are much more sensitive. After the first phase of adaptation, you can see better but not well; after the second phase, your vision is as good as it will ever get.

Rods and cones are connected by synapses to bipolar cells, which in turn communicate with neurons called ganglion cells (see Figure6.6). The axons of the ganglion cells converge to form the optic nerve, which carries information out through the back of the eye and on to the brain.

Figure6.6

The Structures of the Retina

For clarity, all cells in this drawing are greatly exaggerated in size. To reach the receptors for vision (the rods and cones), light must pass through the ganglion and bipolar cells as well as the blood vessels that nourish them (not shown). Normally, we do not see the shadow cast by this network of cells and blood vessels because the shadow always falls on the same place on the retina, and such stabilized images are not sensed. But when an eye doctor shines a moving light into your eye, the treelike shadow of the blood vessels falls on different regions of the retina and you may see it—a rather eerie experience.

Where the optic nerve leaves the eye, at the optic disk, there are no rods or cones. The absence of receptors produces a blind spot in the field of vision. Normally, we are unaware of the blind spot because (1) the image projected on the spot is hitting a different, “nonblind” spot in the other eye; (2) our eyes move so fast that we can pick up the complete image; and (3) the brain fills in the gap. You can use Figure6.7 to find your blind spot.

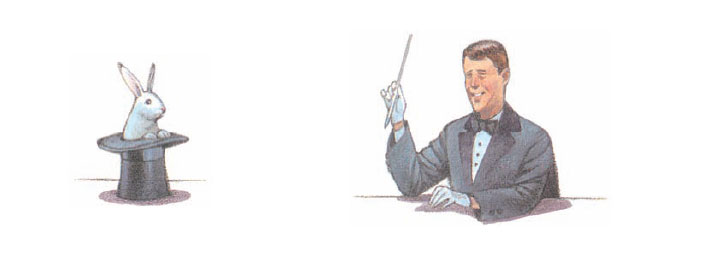

Figure 6.7

Find Your Blind Spot

A blind spot exists where the optic nerve leaves the back of your eye. Find the blind spot in your left eye by closing your right eye and looking at the magician. Then slowly move the image toward and away from yourself. The rabbit should disappear when the image is between 9 and 12 inches from your eye.

Why the Visual System Is Not a Camera

Although the eye is often compared with a camera, the visual system, unlike a camera, is not a passive recorder of the external world. Neurons in the visual system actively build up a picture of the world by detecting its meaningful features.

Ganglion cells and neurons in the thalamus of the brain respond to simple features in the environment, such as spots of light and dark. But in mammals, special feature-detector cells in the visual cortex respond to more complex features. This fact was first demonstrated by David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel (1962, 1968), who painstakingly recorded impulses from individual cells in the brains of cats and monkeys. In 1981, they were awarded a Nobel Prize for their work. Hubel and Wiesel found that different neurons were sensitive to different patterns projected on a screen in front of an animal's eyes. Most cells responded maximally to moving or stationary lines that were oriented in a particular direction and located in a particular part of the visual field. One type of cell might fire most rapidly in response to a horizontal line in the lower right part of the visual field, another to a diagonal line at a specific angle in the upper left part of the visual field. In the real world, such features make up the boundaries and edges of objects.

Since this pioneering work was done, scientists have found that other cells in the visual system have even more specialized roles. A group of cells at the bottom of the cerebral cortex, just above the cerebellum, responds much more strongly to faces than objects—human faces, animal faces, even cartoon faces. Evolutionary psychologists observe that a faculty for deciphering faces makes sense because it would have ensured our ancestors' ability to quickly distinguish friend from foe, or in the case of infants, mothers from strangers. This faculty could help explain why infants prefer looking at faces instead of images that scramble the features of a face, and why a person with brain damage may continue to recognize faces even after losing the ability to recognize other objects. Another area, a part of the cortex near the hippocampus, makes sure you understand your environment: It responds to images of all kinds of places, from your dorm room to an open park, and does so far more strongly than to objects or faces. And a third region, a part of the occipital cortex, responds selectively to bodies and body parts much more strongly than to faces or objects—and more strongly to other people's bodies than to a person's own (Pitcher et al., 2012).

Cases of brain damage support the idea that particular systems of brain cells are highly specialized for identifying important objects or visual patterns, such as faces. One man’s injury left him unable to identify ordinary objects, which, he said, often looked like “blobs.” Yet he had no trouble with faces, even when they were upside down or incomplete. When shown this painting, he could easily see the face but he could not see the vegetables comprising it (Moscovitch, Winocur, & Behrmann, 1997).

Do other brain regions help us perceive additional important features of our environment, such as a laptop or a coffeepot? Researchers have studied 20 different classes of objects, from tools to predators to chairs, and so far have found no other specialized areas (Downing et al., 2006). This is understandable because the brain cannot possibly contain a dedicated area for every conceivable object. In general, the brain's job is to take fragmentary information about edges, angles, shapes, motion, brightness, texture, and patterns and figure out that a chair is a chair and the thing next to it is a dining room table. The perception of any given object probably depends on the activation of many cells in far-flung parts of the brain and on the overall pattern and rhythm of their activity. Keep in mind, too,that experiences change and shape the brain. Thus, some of the brain cells that are supposedly dedicated to face recognition respond to other things as well, depending on a person's experiences and interests. In one study, “face” cells fired when car buffs examined pictures of classic cars but not when they looked at pictures of exotic birds; the exact opposite was true for birdwatchers (Gauthier et al., 2000). You can learn more about face perception by watching the video Recognizing Faces.

Watch

Recognizing Faces

How We See Colors

For over 300 years, scientists have been trying to figure out why we see the world in living color. We now know that different processes explain different stages of color vision.

The Trichromatic Theory The trichromatic theory (also known as the Young-Helmholtz theory) applies to the first level of processing, which occurs in the retina of the eye. The retina contains three basic types of cones. One type responds maximally to blue, another to green, and a third to red. The thousands of colors we see result from the combined activity of these three types of cones.

Total color blindness is usually due to a genetic variation that causes cones of the retina to be absent or malfunction. The visual world then consists of black, white, and shades of gray. Many species of animals are totally color-blind, but the condition is extremely rare in human beings. Most “color-blind” people are actually color deficient, due to an absence of, or damage to, one or more types of cones. Usually, the person is unable to distinguish red and green; the world is painted in shades of blue, yellow, brown, and gray. In rarer instances, a person may be blind to blue and yellow and may see only reds, greens, and grays. Color deficiency is found in about 8 percent of white men, 5 percent of Asian men, and 3 percent of black men and Native American men (Sekuler & Blake, 1994). Because of the way the condition is inherited, it is rare in women.

The Opponent-Process Theory The opponent-process theory applies to the second stage of color processing, which occurs in ganglion cells in the retina and in neurons in the thalamus and visual cortex of the brain. These cells, known as opponent-process cells, either respond to short wavelengths but are inhibited from firing by long wavelengths, or vice versa (DeValois & DeValois, 1975). Some opponent-process cells respond in opposite fashion to red and green, or to blue and yellow; that is, they fire in response to one and turn off in response to the other. (A third system responds in opposite fashion to white and black and thus yields information about brightness.) The net result is a color code that is passed along to the higher visual centers. Because this code treats red and green, and also blue and yellow, as antagonistic, we can describe a color as bluish green or yellowish green but not as reddish green or yellowish blue.

Opponent-process cells that are inhibited by a particular color produce a burst of firing when the color is removed, just as they would if the opposing color were present. Similarly, cells that fire in response to a color stop firing when the color is removed, just as they would if the opposing color were present. These facts explain why we are susceptible to negative afterimages when we stare at a particular hue—why we see, for instance, red after staring at green. (To see this effect for yourself, see Figure6.8.) A sort of neural rebound effect occurs: The cells that switch on or off to signal the presence of “green” send the opposite signal (“red”) when the green is removed and vice versa.

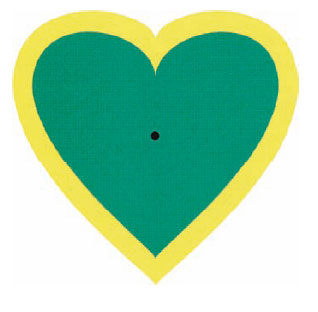

Figure 6.8

A Change of Heart

Opponent-process cells that switch on or off in response to green send an opposite message—“red”—when the green is removed, producing a negative afterimage. Stare at the black dot in the middle of this heart for at least 20 seconds. Then shift your gaze to a white piece of paper or a white wall. Do you get a “change of heart”? You should see an image of a red or pinkish heart with a blue border.

Constructing the Visual World

We do not actually see a retinal image; the mind must actively interpret the image and construct the world from the often-fragmentary data of the senses. In the brain, sensory signals that give rise to vision, hearing, taste, smell, and touch are combined from moment to moment to produce a unified model of the world. This is the process of perception.

Ambiguous Figures

Form Perception To make sense of the world, we must know where one thing ends and another begins. In vision, we must separate the teacher from the lectern; in hearing, we must separate the piano solo from the orchestral accompaniment; in taste, we must separate the marshmallow from the hot chocolate. This process of dividing up the world occurs so rapidly and effortlessly that we take it completely for granted, until we must make out objects in a heavy fog or words in the rapid-fire conversation of someone speaking a language we don't know.

Gestalt psychologists, who belonged to a movement that began in Germany and was influential in the 1920s and 1930s, were among the first to study how people organize the world visually into meaningful units and patterns. In German, Gestalt means “form” or “configuration.” Gestalt psychologists' motto was “The whole is more than the sum of its parts.” They observed that when we perceive something, properties emerge from the configuration as a whole that are not found in any particular component. A modern example of the Gestalt effect occurs when you watch a movie. The motion you see is nowhere in the film, which consists of separate frames projected at (usually) 24 frames per second.

Gestalt psychologists also noted that people organize the visual field into figure and ground. The figure stands out from the rest of the environment (see Figure6.9). Some things stand out as figure by virtue of their intensity or size; it is hard to ignore the bright light of a flashlight at night or a tidal wave approaching your piece of beach. Unique objects also stand out, such as a banana in a bowl of oranges, and so do moving objects in an otherwise still environment, such as a shooting star. Indeed, it is hard to ignore a sudden change of any kind in the environment because our brains are geared to respond to change and contrast. However, selective attention—the ability to concentrate on some stimuli and to filter out others—gives us some control over what we perceive as figure and ground, and sometimes it blinds us to things we would otherwise interpret as figure, as we saw earlier.

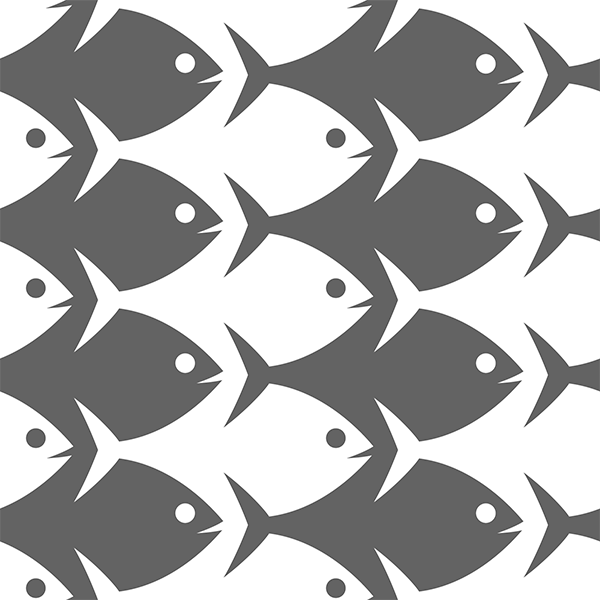

Figure 6.9

Figure and Ground

Which do you notice first in this drawing—the white fish or the black fish?

Other Gestalt principles describe strategies used by the visual system to group sensory building blocks into perceptual units (Köhler, 1929; Wertheimer, 1923/1958). Gestalt psychologists believed that these strategies were present from birth or emerged early in infancy as a result of maturation. Modern research, however, suggests that at least some of them depend on experience (Quinn & Bhatt, 2012). Here are a few well-known Gestalt principles:

Gestalt Principles

Unfortunately, consumer products are sometimes designed with little thought for Gestalt principles, which is why it can be a major challenge to, say, operate the correct dials on a new stovetop (Norman, 2004, 1988). Good design requires, among other things, that crucial distinctions be visually obvious. Watch the video Perceptual Magic in Art 1 to learn more about how cues in the environment influence our perceptions.

Watch

Perceptual Magic in Art 1

Depth and Distance Perception Ordinarily we need to know not only what something is but also where it is. Touch gives us this information directly, but vision does not, so we must infer an object's location by estimating its distance or depth.

To perform this remarkable feat, we rely in part on binocular cues, cues that require the use of two eyes. One such cue is convergence, the turning of the eyes inward, which occurs when they focus on a nearby object. The closer the object, the greater the convergence, as you know if you have ever tried to cross your eyes by looking at your own nose. As the angle of convergence changes, the corresponding muscular changes provide information to the brain about distance.

The two eyes also receive slightly different retinal images of the same object. You can prove this by holding a finger about 12 inches in front of your face and looking at it with only one eye at a time. Its position will appear to shift when you change eyes. Now hold up two fingers, one closer to your nose than the other. Notice that the amount of space between the two fingers appears to change when you switch eyes. The slight difference in lateral (sideways) separation between two objects as seen by the left eye and the right eye is called retinal disparity. Because retinal disparity decreases as the distance between two objects increases, the brain can use it to infer depth and calculate distance.

Binocular cues help us estimate distances up to about 50 feet. For objects farther away, we use only monocular cues, cues that do not depend on using both eyes. One such cue is interposition: When an object is interposed between the viewer and a second object, partly blocking the view of the second object, the first object is perceived as being closer. Another monocular cue is linear perspective: When two lines known to be parallel appear to be coming together or converging (say, railroad tracks), they imply the existence of depth. These and other monocular cues are illustrated here.

Monocular Cues to Depth

Visual Constancies: When Seeing Is Believing Your perceptual world would be a confusing place without still another important perceptual skill. Lighting conditions, viewing angles, and the distances of stationary objects are all continually changing as we move about, yet we rarely confuse these changes with changes in the objects themselves. This ability to perceive objects as stable or unchanging even though the sensory patterns they produce are constantly shifting is called perceptual constancy. The best-studied constancies are visual and include the following:

Size constancy. We see an object as having a constant size even when its retinal image becomes smaller or larger. A friend approaching on the street does not seem to be growing; a car pulling away from the curb does not seem to be shrinking. Size constancy depends in part on familiarity with objects; you know that people and cars do not change size from moment to moment. It also depends on the apparent distance of an object. An object that is close produces a larger retinal image than the same object farther away, and the brain takes this into account. When you move your hand toward your face, your brain registers the fact that the hand is getting closer, and you correctly perceive its unchanging size despite the growing size of its retinal image. There is, then, an intimate relationship between perceived size and perceived distance.

Shape constancy. We continue to perceive an object as having a constant shape even though the shape of the retinal image produced by the object changes when our point of view changes. If you hold a Frisbee directly in front of your face, its image on the retina will be round. When you set the Frisbee on a table, its image becomes elliptical, yet you continue to see it as round.

Location constancy. We perceive stationary objects as remaining in the same place even though the retinal image moves about as we move our eyes, head, and body. As you drive along the highway, telephone poles and trees fly by on your retina. But you know that these objects do not move on their own, and you also know that your body is moving, so you perceive the poles and trees as staying put.

Brightness constancy. We see objects as having a relatively constant brightness even though the amount of light they reflect changes as the overall level of illumination changes. Snow remains white even on a cloudy day, and a black car remains black even on a sunny day. We are not fooled because the brain registers the total illumination in the scene and automatically adjusts for it.

Color constancy. We see an object as maintaining its hue despite the fact that the wavelength of light reaching our eyes from the object may change as the illumination changes. Outdoor light is “bluer” than indoor light, and objects outdoors therefore reflect more “blue” light than those indoors. Conversely, indoor light from incandescent lamps is rich in long wavelengths and is therefore “yellower.” Yet an apple looks red whether you look at it in your kitchen or outside on the patio.

Part of the explanation involves sensory adaptation, which we discussed earlier. Outdoors, we quickly adapt to short-wavelength (bluish) light, and indoors, we adapt to long-wavelength light. As a result, our visual responses are similar in the two situations. Also, when computing the color of a particular object, the brain takes into account all the wavelengths in the visual field immediately around the object. If an apple is bathed in bluish light, so, usually, is everything else around it. The increase in blue light reflected by the apple is canceled in the visual cortex by the increase in blue light reflected by the apple's surroundings, and so the apple continues to look red. Color constancy is further aided by our knowledge of the world. We know that apples are usually red and bananas are usually yellow, and the brain uses that knowledge to recalibrate the colors in those objects when the lighting changes (Mitterer & de Ruiter, 2008).

Visual Illusions: When Seeing Is Misleading Perceptual constancies allow us to make sense of the world. Occasionally, however, we can be fooled, and the result is a perceptual illusion. For psychologists, illusions are valuable because they are systematic errors that provide us with hints about the perceptual strategies of the mind.

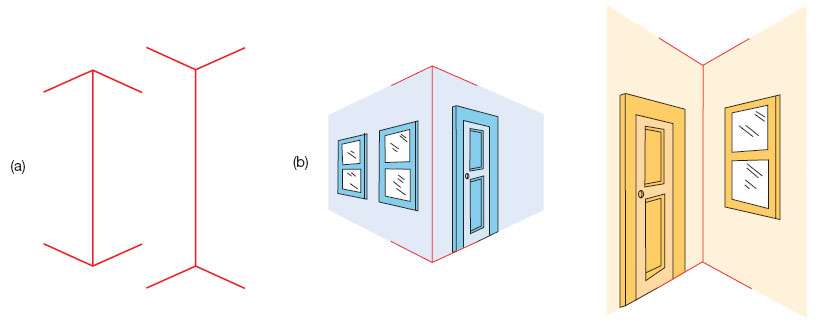

Although illusions can occur in any sensory modality, visual illusions have been the best studied. Visual illusions sometimes occur when the strategies that normally lead to accurate perception are overextended to situations where they do not apply. Compare the lengths of the two vertical lines in Figure6.10a. You will probably perceive the line on the right as slightly longer than the one on the left, yet they are exactly the same. (Go ahead, measure them; everyone does.) This is the Müller-Lyer illusion, named after the German sociologist who first described it in 1889.

Figure 6.10

The Müller-Lyer Illusion

The two lines in (a) are exactly the same length. We are probably fooled into perceiving them as different because the brain interprets the one with the outward-facing branches as farther away, as if it were the far corner of a room, and the one with the inward-facing branches as closer, as if it were the near edge of a building (b).

One explanation for the Müller-Lyer illusion is that the branches on the lines serve as perspective cues that normally suggest depth (Bulatov et al., 2015; Gregory, 1963). The line on the left is like the near edge of a building; the one on the right is like the far corner of a room (see Figure6.10b). Although the two lines produce retinal images of the same size, the one with the outward-facing branches suggests greater distance. We are fooled into perceiving it as longer because we automatically apply a rule about the relationship between size and distance that is normally useful: When two objects produce the same-sized retinal image and one is farther away, the farther one is larger. The problem, in this case, is that the two lines do not actually differ in length, so the rule is inappropriate.

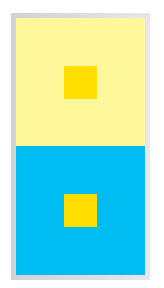

Just as there are size, shape, location, brightness, and color constancies, so there are size, shape, location, brightness, and color in constancies, resulting in illusions. The perceived color of an object depends on the wavelengths reflected by its immediate surroundings, a fact well known to artists and interior designers. Thus, you never see a good, strong red unless other objects in the surroundings reflect the blue and green part of the spectrum. When two objects that are the same color have different surroundings, you may mistakenly perceive them as different (see Figure6.11).

Figure 6.11

Color in Context

The way you perceive a color depends on the color surrounding it. In this example, the small squares are exactly the same color and brightness.

The Muller-Lyer Illusion

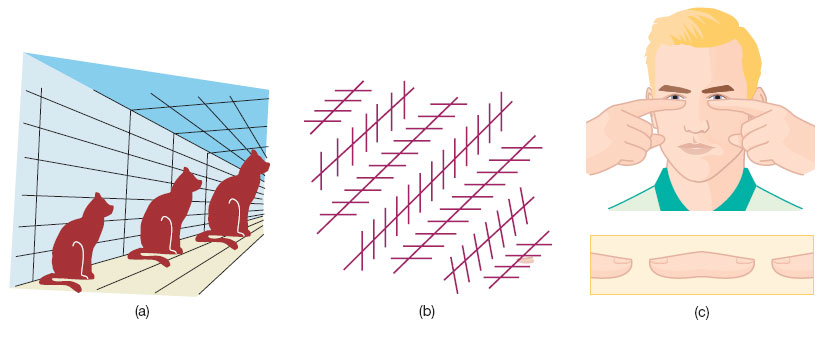

Some illusions are simply a matter of physics. Thus, a chopstick in a half-filled glass of water looks bent because water and air refract light differently. Other illusions occur due to misleading messages from the sense organs, as in sensory adaptation. Still others occur because the brain misinterprets sensory information, as in the Müller-Lyer illusion and the illusions in Figure6.12.

Figure 6.12

Fooling the Eye

Although perception is usually accurate, we can be fooled. In (a), the cats as drawn are exactly the same size; in (b), the diagonal lines are all parallel. To see the illusion depicted in (c), hold your index fingers 5 to 10 inches in front of your eyes as shown and then focus straight ahead. Do you see a floating “fingertip frankfurter”? Can you make it shrink or expand?

Perhaps the ultimate perceptual illusion occurred when Swedish researchers tricked people into feeling that they were swapping bodies with another person or even a mannequin (Petkova & Ehrsson, 2008). The participants wore virtual-reality goggles connected to a camera on the other person's (or mannequin's) head. This allowed them to see the world from the other body's point of view as an experimenter simultaneously stroked both bodies with a rod. Most people soon had the weird sensation that the other body was actually their own; they even cringed when the other body was poked or threatened. The researchers speculate that the body-swapping illusion could some day be helpful in marital counseling, allowing each partner to literally see things from the other's point of view, or in therapy with people who have distorted body images (Ahn, Le, & Bailenson, 2013).

Talk about an illusion! The person on the left is wearing virtual-reality goggles, and the mannequin on the right is outfitted with a camera that feeds images to the goggles. As a result, the person quickly comes to feel as though he has swapped bodies with the mannequin.

In everyday life, most illusions are harmless and entertaining. Occasionally, however, an illusion interferes with the performance of some task or skill, or may even cause an accident. For example, because large objects often appear to move more slowly than small ones, some drivers underestimate the speed of onrushing trains at railroad crossings. They think they can beat the train, with tragic results.