7.1

Classical Conditioning

We will begin our exploration of learning with a look at classical conditioning. Watch Classical Conditioning: An Involuntary Response to get an overview of the principles and applications we’ll be discussing.

Watch

Classical Conditioning: An Involuntary Response

New Reflexes from Old

At the turn of the 20th century, the great Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) was studying salivation in dogs as part of a research program on digestion. One of his procedures was to make a surgical opening in a dog's cheek and insert a tube that conducted saliva away from the animal's salivary gland so that the saliva could be measured. To stimulate the reflexive flow of saliva, Pavlov placed meat powder or other food in the dog's mouth (see Figure7.1).

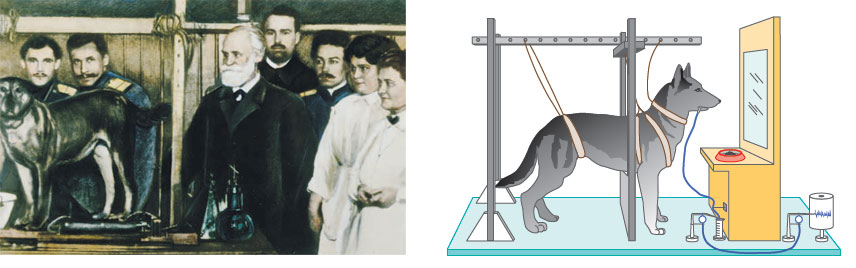

Figure 7.1

Pavlov's Method

The photo shows Ivan Pavlov (in the white beard), flanked by his students and a canine subject. The drawing depicts an apparatus similar to the one he used; saliva from a dog's cheek flowed down a tube and was measured by the movement of a needle on a revolving drum.

Pavlov was a truly dedicated scientific observer. Many years later, as he lay dying, he even dictated his sensations for posterity! And he instilled in his students and assistants the same passion for detail. During his salivation studies, one of the assistants noticed something that most people would have overlooked or dismissed as trivial. After a dog had been brought to the laboratory a few times, it would start to salivate before the food was placed in its mouth. The sight or smell of the food, the dish in which the food was kept, and even the sight of the person who delivered the food were enough to start the dog's mouth watering. These new salivary responses clearly were not inborn, so they must have been acquired through experience.

At first, Pavlov treated the dog's drooling as just an annoying secretion. But he quickly realized that his assistant had stumbled onto an important phenomenon, one that Pavlov came to believe was the basis of most learning in human beings and other animals (Pavlov, 1927). He called that phenomenon a “conditional” reflex because it depended on environmental conditions. Later, an error in the translation of his writings transformed “conditional” into “conditioned,” the word most commonly used today. Such conditioning came to refer to a basic kind of learning based on association.

Pavlov soon dropped what he had been doing and turned to the study of conditioned reflexes, to which he devoted the last three decades of his life. Why were his dogs salivating to things other than food? Pavlov initially speculated about what his dogs might be thinking and feeling when they drooled before getting their food. Was the doggy equivalent of “Oh boy, this means chow time” going through their minds? He soon decided, however, that such speculation was pointless. Instead, he focused on analyzing the environment in which the conditioned reflex arose.

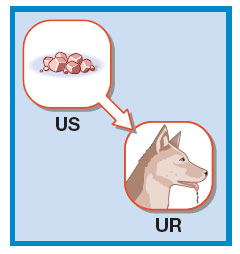

The original salivary reflex, according to Pavlov, consisted of an unconditioned stimulus (US), food in the dog's mouth, and an unconditioned response (UR), salivation. By an unconditioned stimulus, Pavlov meant a thing or event that already produces a certain response without additional learning. By an unconditioned response, he meant the response that is produced:

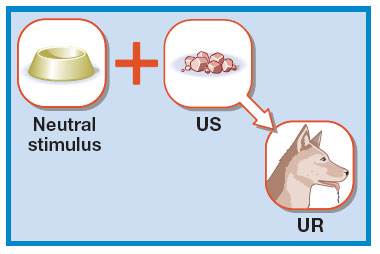

In Pavlov's lab, when some neutral stimulus such as the dish—a stimulus that did not typically cause the dog to salivate—was regularly paired with food, the dog learned to associate the dish and the food. As a result, the dish alone acquired the power to make the dog salivate:

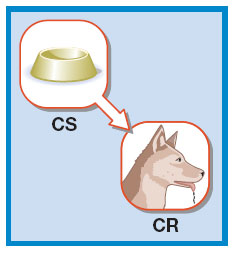

More generally, as a neutral stimulus and US become associated, the neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS). The CS then has the capacity to elicit a learned or conditioned response (CR) that is usually similar or related to the original, unlearned one. In Pavlov's laboratory, the sight of the food dish, which had not previously elicited salivation, became a CS for salivation:

The procedure by which a previously neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus eventually became known as classical conditioning and is sometimes also called Pavlovian or respondent conditioning. Pavlov and his students went on to show that all sorts of things can become conditioned stimuli for salivation if they are paired with food: the ticking of a metronome, the musical tone of a bell, the vibrating sound of a buzzer, a touch on the leg, even a pinprick or an electric shock.

Review7.1

Terms Used in Classical Conditioning 1

Principles of Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning occurs in all species, from one-celled amoebas to Homo sapiens. Many responses besides salivation have been classically conditioned, including heartbeat, blood pressure, alertness, hunger, and sexual arousal. In the laboratory, the optimal interval between the presentation of the neutral stimulus and the presentation of the US is often quite short, sometimes less than a second. Let's look more closely at some of classical conditioning's other important features: extinction, higher-order conditioning, and stimulus generalization and discrimination.

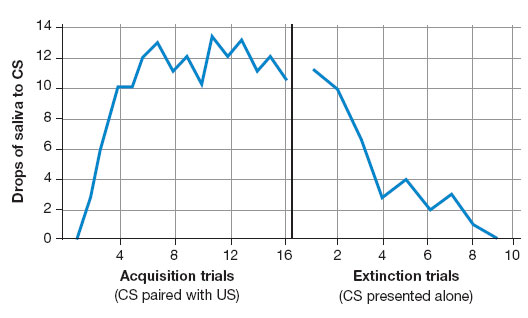

Extinction Conditioned responses can persist for months or years. But if a conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus, the conditioned response will weaken and may eventually disappear, a process known as extinction (see Figure7.2). Suppose that you train your dog Milo to salivate to the sound of a bell, but then you ring the bell every 5 minutes and do not follow it with food. Milo will salivate less and less to the bell and will soon stop salivating altogether; salivation will have been extinguished. Extinction, however, is not the same as unlearning. If you come back the next day and ring the bell, Milo may salivate again for a few trials, although the response will probably be weaker. The reappearance of the response, called spontaneous recovery, explains why completely eliminating a conditioned response often requires more than one extinction session.

Figure 7.2

Acquisition and Extinction of a Salivary Response

A neutral stimulus that is consistently followed by an unconditioned stimulus for salivation will become a conditioned stimulus for salivation (left side of graph). But when this conditioned stimulus is then repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus, the conditioned salivary response will weaken and eventually disappear; it has been extinguished.

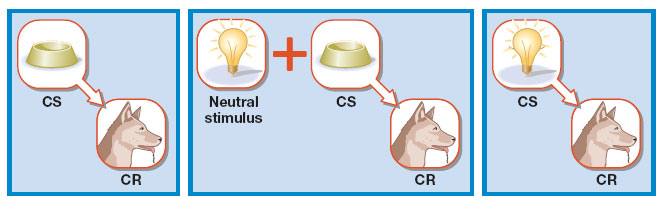

Higher-Order Conditioning Sometimes a neutral stimulus can become a conditioned stimulus by being paired with an already established CS, a procedure known as higher-order conditioning. Say Milo has learned to salivate to the sight of his food dish. Now you flash a bright light before presenting the dish. With repeated pairings of the light and the dish, Milo may learn to salivate to the light. The procedure for higher-order conditioning is illustrated in Figure7.3.

Figure 7.3

Higher-Order Conditioning

In this illustration of higher-order conditioning, the food dish is a previously conditioned stimulus for salivation (left). When the light, a neutral stimulus, is paired with the dish (center), the light also becomes a conditioned stimulus for salivation (right).

Higher-order conditioning may explain why some words trigger emotional responses in us—why they can inflame us to anger or evoke warm, sentimental feelings. When words are paired with objects or other words that already elicit some emotional response, they too may come to elicit that response (Staats & Staats, 1957). A child may learn a positive response to the word birthday because of its association with gifts and attention. Conversely, the child may learn a negative response to ethnic or national labels if the labels are paired with words that the child has already learned are disagreeable, such as dumb or dirty. Higher-order conditioning, in other words, may contribute to the formation of prejudices.

Stimulus Generalization and Discrimination After a stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus for some response, similar stimuli may produce a similar reaction, a phenomenon known as stimulus generalization. If you condition your patient pooch Milo to salivate to middle C on the piano, Milo may also salivate to D, which is one tone above C, even though you did not pair D with food. Stimulus generalization is described nicely by an old English proverb: “He who hath been bitten by a snake fears a rope.”

The mirror image of stimulus generalization is stimulus discrimination, in which different responses are made to stimuli that resemble the conditioned stimulus in some way. Suppose that you have conditioned Milo to salivate to middle C on the piano by repeatedly pairing the sound with food. Now you play middle C on a guitar, without following it by food (but you continue to follow C on the piano by food). Eventually, Milo will learn to salivate to a C on the piano and not to salivate to the same note on the guitar; that is, he will discriminate between the two sounds. If you keep at this long enough, you could train Milo to be a pretty discriminating drooler!

Review7.2

Terms Used in Classical Conditioning 2

What Is Actually Learned in Classical Conditioning?

A critical feature of classical conditioning is that the animal or person learns to associate stimuli, rather than learning to associate a stimulus with a response. Milo will learn to salivate to the bell because he has learned to associate the bell with food, not (as is commonly thought) because he has learned to associate the bell with salivating. For classical conditioning to be most effective, the stimulus to be conditioned should precede the unconditioned stimulus rather than follow it or occur simultaneously with it. This makes sense because in classical conditioning the conditioned stimulus becomes a signal for the unconditioned stimulus. Classical conditioning is in fact an evolutionary adaptation, one that enables the organism to anticipate and prepare for a biologically important event that is about to happen. In Pavlov's studies, for instance, a bell, buzzer, or other stimulus was a signal that meat was coming, and the dog's salivation was preparation for digesting food. Today, therefore, many psychologists contend that what an animal or person actually learns in classical conditioning is not merely an association between two paired stimuli that occur close together in time, but rather information conveyed by one stimulus about another: “If a tone sounds, food is likely to follow.”

This view is supported by the research of Robert Rescorla (1988, 2008), who showed, in a series of imaginative studies, that the mere pairing of an unconditioned stimulus and a neutral stimulus is not enough to produce learning. To become a conditioned stimulus, the neutral stimulus must reliably signal, or predict, the unconditioned stimulus. If food occurs just as often without a preceding tone as with it, the tone is unlikely to become a conditioned stimulus for salivation because the tone does not provide any information about the probability of getting food. Think of it this way: If every phone call you got brought bad news that made your heart race, your heart might soon start pounding every time the phone rang—a conditioned response. Ordinarily, though, upsetting calls occur randomly among a far greater number of routine ones. The ringtone may sometimes be paired with bad news, but it doesn't always signal disaster, so no conditioned heart-rate response occurs.

Rescorla concluded that “Pavlovian conditioning is not a stupid process by which the organism willy-nilly forms associations between any two stimuli that happen to co-occur. Rather, the organism is better seen as an information seeker using logical and perceptual relations among events, along with its own preconceptions, to form a sophisticated representation of its world.” Not all learning theorists agree; an orthodox behaviorist would say that it is silly to talk about the preconceptions of a rat. The important point, however, is that concepts such as “information seeking,” “preconceptions,” and “representations of the world” open the door to a more cognitive view of classical conditioning.

Try out your behavioral skills by conditioning an eyeblink response in a willing friend, using classical-conditioning procedures. You will need a drinking straw and something to make a ringing sound; a spoon tapped on a water glass works well. Tell your friend that you are going to use the straw to blow air in his or her eye, but do not say why. Immediately before each puff of air, make the ringing sound. Repeat this procedure 10 times. Then make the ringing sound but don't puff. Your friend will probably blink anyway, and may continue to do so for one or two more repetitions of the sound before the response extinguishes. Can you identify the US, the UR, the CS, and the CR in this exercise?