7.6

Learning and the Mind

For half a century, most American learning theories held that learning could be explained by specifying the behavioral “ABCs”: antecedents (events preceding behavior), behaviors, and consequences. Behaviorists liked to compare the mind to an engineer's hypothetical “black box,” a device whose workings must be inferred because they cannot be observed directly. To them, the box contained irrelevant wiring; it was enough to know that pushing a button on the box would produce a predictable response. But even as early as the 1930s, a few behaviorists could not resist peeking into that black box.

Latent Learning

Behaviorist Edward Tolman (1938) committed virtual heresy at the time by noting that his rats, when pausing at turning points in a maze, seemed to be deciding which way to go. Moreover, the animals sometimes seemed to be learning even without any reinforcement. What, he wondered, was going on in their little rat brains that might account for this puzzle?

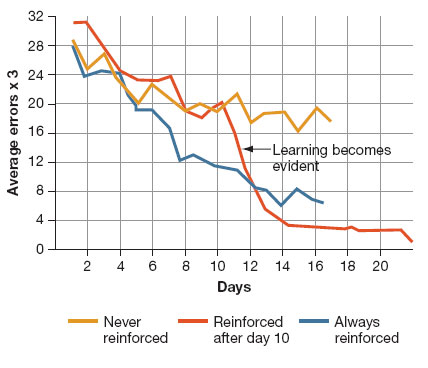

In a classic experiment, Tolman and C. H. Honzik (1930) placed three groups of rats in mazes and observed their behavior daily for more than 2 weeks. The rats in Group 1 always found food at the end of the maze and quickly learned to find it without going down blind alleys. The rats in Group 2 never found food and, as you would expect, they followed no particular route. Group 3 was the interesting group. These rats found no food for 10 days and seemed to wander aimlessly, but on the 11th day they received food, and then they quickly learned to run to the end of the maze. By the following day, they were doing as well as Group 1, which had been rewarded from the beginning (see Figure7.6).

Figure 7.6

Latent Learning

In a classic experiment, rats that always found food in a maze made fewer and fewer errors in reaching the food (blue curve). In contrast, rats that received no food showed little improvement (gold curve). But rats that got no food for 10 days and then found food on the 11th day showed rapid improvement from then on (red curve). This result suggests that learning involves cognitive changes that can occur in the absence of reinforcement and that may not be acted on until a reinforcer becomes available (Tolman & Honzik, 1930).

Group 3 had demonstrated latent learning, learning that is not immediately expressed in performance. A great deal of human learning also remains latent until circumstances allow or require it to be expressed. A driver gets out of a traffic jam and finds her way to Fourth and Kumquat Streets using a route she has never used before (without GPS!). A little boy observes a parent setting the table or tightening a screw but does not act on this learning for years; then he finds he knows how to do these things.

Latent learning raises questions about what, exactly, is learned during operant learning. In the Tolman and Honzik study, the rats that did not get any food until the 11th day seemed to have acquired a mental representation of the maze. They had been learning the whole time; they simply had no reason to act on that learning until they began to find food. Similarly, the driver taking a new route can do so because she already knows how the city is laid out. What seems to be acquired in latent learning, therefore, is not a specific response, but knowledge about responses and their consequences. We learn how the world is organized, which paths lead to which places, and which actions can produce which payoffs. This knowledge permits us to be creative and flexible in reaching our goals.

Latent Learning

Social-Cognitive Learning Theories

During the 1960s and 1970s, many learning theorists concluded that human behavior could not be understood without taking into account the human capacity for higher-level cognitive processes. They agreed with behaviorists that human beings, along with the rat and the rabbit, are subject to the laws of operant and classical conditioning. But they added that human beings, unlike the rat or the rabbit, are full of attitudes, beliefs, and expectations that affect the way they acquire information, make decisions, reason, and solve problems. Today, this view has become very influential.

We will use the term social-cognitive theory for all theories that combine behavioral principles with cognitive ones to explain behavior (Bandura, 1986; Mischel, 1973; Mischel & Shoda, 1995). These theories share an emphasis on the importance of beliefs, perceptions, and observations of other peoples' behavior in determining what we learn, what we do at any given moment, and the personality traits we develop (see Chapter 14). To a social-cognitive theorist, differences in beliefs and perceptions help explain why two people who live through the same event may come away with entirely different lessons from it ( Bandura, 2012). All siblings know this. One sibling may regard being grounded by their father as evidence of his all-around meanness, whereas another may see the same behavior as evidence of his care and concern for his children. For these siblings, being grounded is likely to affect their behavior differently.

Learning by Observing Late one night, a friend living in a rural area was awakened by a loud clattering noise. A raccoon had knocked over a “raccoon-proof” garbage can and seemed to be demonstrating to an assembly of other raccoons how to open it: If you jump up and down on the can's side, the lid will pop off. According to our friend, the observing raccoons learned from this episode how to open stubborn garbage cans, and the observing humans learned how smart raccoons can be. In short, they all benefited from observational learning, learning by watching what others do and what happens to them for doing it.

The behavior learned by the raccoons through observation was an operant one, but observational learning also plays an important role in the acquisition of automatic, reflexive responses, such as fears and phobias (Mineka & Zinbarg, 2006; Olsson & Phelps, 2004). Thus, in addition to learning to be frightened of rats directly through classical conditioning, as Little Albert did, you might also learn to fear rats by observing the emotional expressions of other people when they see or touch one. The perception of someone else's reaction serves as an unconditioned stimulus for your own fear, and the learning that results may be as strong as it would be if you had had a direct encounter with the rat yourself. Children often learn to fear things in this way, perhaps by observing a parent's fearful reaction whenever a dog approaches.

Behaviorists refer to observational learning as vicarious conditioning, and believe it can be explained in stimulus–response terms. But social-cognitive theorists believe that observational learning in human beings cannot be fully understood without taking into account the thought processes of the learner (Meltzoff & Gopnik, 1993). They emphasize the knowledge that results when a person sees a model—another person—behaving in certain ways and experiencing the consequences (Bandura, 1977).

None of us would last long without observational learning. Learning would be both inefficient and dangerous. We would have to learn to avoid oncoming cars by walking into traffic and suffering the consequences, or learn to swim by jumping into a deep pool and flailing around. Parents and teachers would be busy 24 hours a day shaping children's behavior. Bosses would have to stand over their employees' desks, rewarding every little link in the complex behavioral chains we call typing, report writing, and accounting. But observational learning has its dark side as well: People often imitate antisocial or unethical actions (they observe a friend cheating and decide they can get away with it too) or self-defeating and harmful ones (they watch a film star smoking and take up the habit in an effort to look just as cool).

Bandura's Classic Research Many years ago, Albert Bandura and his colleagues showed just how important observational learning is for children who are learning the rules of social behavior (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1963). Nursery school children watched a short film of two men, Rocky and Johnny, playing with toys. (Apparently the children did not think this behavior was the least bit odd.) In the film, Johnny refuses to share his toys, and Rocky responds by clobbering him. Rocky's aggressive actions are rewarded because he winds up with all the toys. Poor Johnny sits dejectedly in the corner, while Rocky marches off with a sack full of loot and a hobbyhorse under his arm.

After viewing the film, each child was left alone for 20 minutes in a playroom full of toys, including some of the items shown in the film. Watching through a one-way mirror, the experimenters found that the children were much more aggressive in their play than a control group that had not seen the film. Some children imitated Rocky almost exactly. At the end of the session, one little girl even asked for a sack!

Findings on latent learning, observational learning, and the role of cognition in learning can help us evaluate arguments in the passionate debate about the effects of media violence. Children and teenagers in the United States and many other countries see countless acts of violence on television, in films, and in video games. Does all this mayhem of blood and guts affect them? Do you think it has affected you? In “Taking Psychology with You,” we offer evidence that bears on these questions, and suggest ways of resolving them without oversimplifying the issues.

Observational Learning of Aggressive Response