8.1

Social Forces

Imagine the life of a hermit. Completely cut off from society, you'd be able to do whatever you want whenever you want, not have to answer to anyone else, not have to meet anyone's expectations, and never have to interact with another human being. In some ways that might sound ideal, but in actuality you'd probably find that the absence of other people had a debilitating effect on you. Humans are social animals, and we pay a high price for loneliness, isolation, and social exclusion (Cacioppo et al., 2015; Freidler, Capser, & McCullough, 2015; Stillman & Baumeister, 2013). Yet sometimes it seems we pay an equally high price for social engagement. When humans agree to live in interactive social arrangements, a complex set of rules, expectations, and standards are an implicit part of the bargain.

Roles and Rules

“We are all fragile creatures entwined in a cobweb of social constraints,” social psychologist Stanley Milgram once said. The constraints he referred to are social norms, rules about how we are supposed to act, enforced by threats of punishment if we violate them and promises of reward if we follow them. Norms are the conventions of everyday life that make interactions with other people predictable and orderly; like a cobweb, they are often as invisible as they are strong. Every society has norms for just about everything in human experience: for conducting courtships, for raising children, for making decisions, for behavior in public places. Some norms are enshrined in law, such as “A person may not beat up another person, except in self-defense.” Some are unspoken cultural understandings, such as “A man may beat up another man who insults his masculinity.” And some are tiny, unspoken regulations that people follow unconsciously, such as “You may not sing at the top of your lungs on a public bus.”

When people observe that “everyone else” seems to be violating a social norm, they are more likely to do so too—and this is the mechanism by which entire neighborhoods can deteriorate. In six natural field experiments conducted in the Netherlands, passersby were more likely to litter, to park illegally, and even to steal a five-euro bill from a mailbox if the sidewalks were dirty and unswept, if graffiti marked the walls, or if strangers were setting off illegal fireworks (Keizer, Linderberg, & Steg, 2008).

Either alone or with a friend, try a mild form of norm violation (nothing alarming, obscene, dangerous, or offensive). You might stand backward in line at the grocery store or cafeteria; sit right next to a stranger in the library or at a movie, even when other seats are available; sing or hum loudly for a couple of minutes in a public place; or stand “too close” to a friend in conversation. Notice the reactions of onlookers, as well as your own feelings, while you violate this norm. If you do this exercise with someone else, one of you can be the “violator” and the other can write down the responses of others; then switch places. Was it easy to do this exercise? Why or why not?

In every society, people also fill a variety of social roles, positions that are regulated by norms about how people in those positions should behave. Gender roles define the proper behavior for a man and a woman. Occupational roles determine the correct behavior for a manager and an employee, a professor and a student. Family roles set tasks for parent and child. Certain aspects of every role must be carried out or there will be penalties—emotional, financial, or professional. As a student, you know just what you have to do to pass your psychology course (or you should by now). How do you know what a role requirement is? You know when you violate it, intentionally or unintentionally, because you will probably feel uncomfortable, or other people will try to make you feel that way.

The requirements of a social role are in turn shaped by the culture you live in. Culture can be defined as a program of shared rules that govern the behavior of people in a community or society, and a set of values, beliefs, and customs shared by most members of that community and passed from one generation to another (Lonner, 1995). You learn most of your culture's rules and values the way you learn your culture's language: without thinking about it.

One cultural norm governs the rules for conversational distance: how close people normally stand to one another when they are speaking (Hall, 1959, 1976). In general, Arabs like to stand close enough to feel your breath, touch your arm, and see your eyes—a distance that makes most white Americans, Canadians, and northern Europeans uneasy, unless they are talking intimately with a lover. The English and the Swedes stand farthest apart when they converse; southern Europeans stand closer; and Latin Americans and Arabs stand the closest (Keating, 1994; Sommer, 1969). If you are talking to someone who has different cultural rules for distance from yours, you are likely to feel uncomfortable without knowing why. You may feel that the person is crowding you or being strangely distant. A student from Lebanon told us how relieved he was to learn this. “When Anglo students moved away from me, I thought they were prejudiced,” he said. “Now I see why I was more comfortable talking with Latino students. They like to stand close, too.”

Arabs stand much closer in conversation than Westerners do, close enough to feel one another’s breath and “read” one another’s eyes. Most Westerners would feel “crowded” standing so close, even when talking to a friend.

Naturally, people bring their own personalities and interests to the roles they play. Just as two actors will play the same part differently even though they are reading from the same script, you will have your own reading of how to play the role of student, friend, parent, or employee. Nonetheless, the requirements of a social role are strong, so strong that they may even cause you to behave in ways that shatter your fundamental sense of the kind of person you are. We turn now to two classic studies that illuminate the power of social roles in our lives.

The Obedience Study

In the early 1960s, Stanley Milgram (1963, 1974) designed a study that would become world famous. Milgram wanted to know how many people would obey an authority figure when directly ordered to violate their ethical standards. Participants in the study thought they were part of an experiment on the effects of punishment on learning. Each was assigned, apparently at random, to the role of “teacher.” Another person, introduced as a fellow volunteer, was the “learner.” Whenever the learner, seated in an adjoining room, made an error in reciting a list of word pairs he was supposed to have memorized, the teacher had to give him an electric shock by depressing a lever on a machine (see Figure8.1). With each error, the voltage (marked from 0 to 450) was to be increased by another 15 volts. The shock levels on the machine were labeled from SLIGHT SHOCK to DANGER—SEVERE SHOCK and, finally, ominously, XXX. In reality, the learners were confederates of Milgram and did not receive any shocks, but none of the teachers ever realized this during the study. The actor-victims played their parts convincingly: As the study continued, they shouted in pain and pleaded to be released, all according to a prearranged script.

Figure8.1

The Milgram Obedience Experiment

Before doing this study, Milgram asked a number of psychiatrists, students, and other adults how many people they thought would “go all the way” to XXX upon orders from the researcher. The psychiatrists predicted that most people would refuse to go beyond 150 volts, when the learner first demanded to be freed, and that only one person in a thousand, someone who was disturbed and sadistic, would administer the highest voltage. The nonprofessionals agreed with this prediction, and all of them said that they personally would disobey early in the procedure.

That is not, however, the way the results turned out. Every single person administered some shock to the learner, and about two-thirds of the participants, of all ages and from all walks of life, obeyed to the fullest extent. Many protested to the experimenter, but they backed down when he calmly asserted, “The experiment requires that you continue.” They obeyed no matter how much the victim shouted for them to stop and no matter how painful the shocks seemed to be. They obeyed even when they themselves were anguished about the pain they believed they were causing. As Milgram (1974) noted, participants would “sweat, tremble, stutter, bite their lips, groan, and dig their fingernails into their flesh”—but still they obeyed.

Over the decades, more than 3,000 people of many different ethnicities have gone through replications of the Milgram study. Most of them, men and women equally, inflicted what they thought were dangerous amounts of shock to another person. High percentages of obedience occur all over the world, ranging to more than 90 percent in Spain and the Netherlands (Meeus & Raaijmakers, 1995; Smith & Bond, 1994).

Milgram and his team subsequently set up several variations of the study to determine the circumstances under which people might disobey the experimenter. They found that virtually nothing the victim did or said changed the likelihood of compliance, even when the victim said he had a heart condition, screamed in agony, or stopped responding entirely, as if he had collapsed. However, people were more likely to disobey under certain conditions:

When the experimenter left the room, many people subverted authority by giving low levels of shock but reporting that they had followed orders.

When the victim was right there in the room, and the teacher had to administer the shock directly to the victim's body, many people refused to go on.

When two experimenters issued conflicting demands, with one telling participants to continue and another saying to stop at once, no one kept inflicting shock.

When the person ordering them to continue was an ordinary man, apparently another volunteer instead of the authoritative experimenter, many participants disobeyed.

When the participant worked with peers who refused to go further, he or she often gained the courage to disobey.

Obedience, Milgram concluded, was more a function of the situation than of the personalities of the participants. “The key to [their] behavior,” Milgram (1974) summarized, “lies not in pent-up anger or aggression but in the nature of their relationship to authority. They have given themselves to the authority; they see themselves as instruments for the execution of his wishes; once so defined, they are unable to break free.”

The Milgram study has had critics. Some consider it unethical because people were kept in the dark about what was really happening until the session was over (of course, telling them in advance would have invalidated the study) and because many suffered emotional pain (Milgram countered that they would not have felt pain if they had simply disobeyed instructions). The original study could never be repeated in the United States today because of these ethical concerns. However, a “softer” version of the experiment has been done, in which “teachers” who had not heard of the original Milgram study were asked to administer shocks only up to 150 volts, when they first heard the learner protest. That amount of shock had been a critical choice point in Milgram's study, and in the replication, nearly 80 percent of those who went past 150 ended up going all the way to the end (Packer, 2008). Overall obedience rates were only slightly lower than Milgram's, and once again, gender, education, age, and ethnicity had no effect on the likelihood of obeying (Burger, 2009). In another, rather eerie cyberversion replication of Milgram's study, participants had to shock a virtual woman on a computer screen. Even though they knew she wasn't real, their heart rates increased and they reported feeling bad about delivering the “shocks.” Yet they kept doing it (Slater et al., 2006).

Some psychologists have questioned Milgram's conclusion that personality traits are virtually irrelevant to whether people obey an authority. Certain traits, they note, especially hostility, narcissism, and rigidity, do increase obedience and a willingness to inflict pain on others (Blass, 2000; Twenge, 2009). Others have objected to the parallel Milgram drew between the behavior of the study's participants and the brutality of the Nazis and others who have committed acts of barbarity in the name of duty (Darley, 1995). The people in Milgram's study typically obeyed only when the experimenter was hovering right there, and many of them felt enormous discomfort. In contrast, most Nazis acted without direct supervision by authorities, without external pressure, and without feelings of anguish.

Nevertheless, no one disputes that Milgram's compelling study has had a tremendous influence on public awareness of the dangers of uncritical obedience. As John Darley (1995) observed, “Milgram shows us the beginning of a path by means of which ordinary people, in the grip of social forces, become the origins of atrocities in the real world.”

The Prison Study

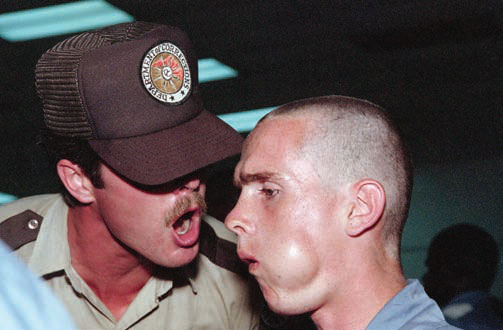

Another famous demonstration of the power of roles is known as the Stanford prison study. Its primary designer, Philip Zimbardo, wanted to know what would happen if ordinary college students were randomly assigned to the roles of prisoners and guards. And so he and his associates set up a serious-looking “prison” in the basement of a Stanford building, complete with individual cells, different uniforms for prisoners and guards, and nightsticks for the guards (Haney, Banks, & Zimbardo, 1973). The students agreed to live there for 2 weeks.

Prisoners and guards quickly learn their respective roles, which often have more influence on their behavior than their personalities do.

Within a short time, most of the prisoners became distressed and helpless. They developed emotional symptoms and physical ailments. Some became apathetic; others became rebellious. One panicked and broke down. The guards, however, began to enjoy their new power. Some tried to be nice, helping the prisoners and doing little favors for them. Some were “tough but fair,” holding strictly to “the rules.” But about a third became punitive and harsh, even when the prisoners were not resisting in any way. One guard became unusually sadistic, smacking his nightstick into his palm as he vowed to “get” the prisoners and instructing two of them to simulate sexual acts (they refused). Zimbardo, who had not expected such a speedy and alarming transformation of ordinary students, ended this study after only 6 days.

Generations of students and the general public have seen emotionally charged clips from videos of the study made at the time. To Zimbardo, the results demonstrated how roles affect behavior: The guards' aggression was entirely a result of wearing a guard's uniform and having the power conferred by a guard's authority (Haney & Zimbardo, 1998). Some social psychologists, however, have argued that the prison study is really another example of obedience to authority and of how willingly some people obey instructions, in this case from Zimbardo himself (Carnahan & McFarland, 2007; Haslam & Reicher, 2003). Consider the briefing that Zimbardo provided to the guards at the beginning of the study:

You can create in the prisoners feelings of boredom, a sense of fear to some degree, you can create a notion of arbitrariness that their life is totally controlled by us, by the system, you, me, and they'll have no privacy. . . . We're going to take away their individuality in various ways. In general what all this leads to is a sense of powerlessness. That is, in this situation we'll have all the power and they'll have none. (The Stanford Prison Study video, quoted in Haslam & Reicher, 2003)

These are pretty powerful suggestions to the guards about how they would be permitted to behave, and they convey Zimbardo's personal encouragement (“We'll have all the power”), so perhaps it is not surprising that some took Zimbardo at his word and behaved quite brutally. The one sadistic guard later said he was just trying to play the role of the “worst S.O.B. guard” he'd seen in the movies. Even the investigators themselves noted at the time that the data were “subject to possible errors due to selective sampling. The video and audio recordings tended to be focused upon the more interesting, dramatic events which occurred” (Haney, Curtis, & Zimbardo, 1973).

Despite these flaws, the Stanford prison study remains a useful cautionary tale. In real prisons, guards do have tremendous power, and they too may be given permission to use that power harshly. Thus the prison study provides a good example of how the social situation affects behavior, causing some people to behave in ways that seem out of character.

Why People Obey

Of course, obedience to authority or to the norms of a situation is not always harmful or bad. A certain amount of routine compliance with rules is necessary in any group, and obedience to authority has many benefits for individuals and society. A nation could not operate if all its citizens ignored traffic signals, cheated on their taxes, dumped garbage wherever they chose, or assaulted each other. A business organization could not function if its members came to work only when they felt like it. But obedience also has a darker aspect. Throughout history, the plea “I was only following orders” has been offered to excuse actions carried out on behalf of orders that were foolish, destructive, or criminal. Writer C. P. Snow once observed that “more hideous crimes have been committed in the name of obedience than in the name of rebellion.”

Most people follow orders because of the obvious consequences of disobedience: They can be suspended from school, fired from their jobs, or arrested. But they may also obey an authority because they hope to gain advantages or promotions or expect to learn from the authority's greater knowledge or experience. They obey because they are dependent on the authority and respect the authority's legitimacy (van der Toorn, Tyler, & Jost, 2011). And, most of all, they obey because they do not want to rock the boat, appear to doubt the experts, or be rude, fearing that they will be disliked or rejected for doing so (Collins & Brief, 1995). But what about all those people in Milgram's study who felt they were doing wrong and who wished they were free, but who could not untangle themselves from the “cobweb of social constraints”? How do people become morally disengaged from the consequences of their actions?

One answer is entrapment, a process in which individuals escalate their commitment to a course of action in order to justify their investment in it (Brockner & Rubin, 1985). The first stages of entrapment may pose no difficult choices, but as people take another step, or make a decision to continue, they will justify that action, which allows them to feel that it is the right one. Before long, the person has become committed to a course of action that is increasingly self-defeating, cruel, or foolhardy.

Thus, in the Milgram study, once participants had given a 15-volt shock, they had committed themselves to the experiment. The next level was “only” 30 volts. Because each increment was small, before they knew it most people were administering what they believed were dangerously strong shocks. At that point, it was difficult to justify a sudden decision to quit, especially after reaching 150 volts, the point at which the “learner” made his first verbal protests. Those who administered the highest levels of shock justified their actions by adopting the attitude of “It's his problem; I'm just following orders,” handing over responsibility to the authority and absolving themselves of accountability for their own actions (Burger, 2014; Kelman & Hamilton, 1989; Modigliani & Rochat, 1995). In contrast, individuals who refused to give high levels of shock justified their decision by taking responsibility for their actions. “One of the things I think is very cowardly,” said a 32-year-old engineer, “is to try to shove the responsibility onto someone else. See, if I now turned around and said, ‘It's your fault . . . it's not mine,’ I would call that cowardly” (Milgram, 1974).

A chilling study of entrapment was conducted with 25 men who had served in the Greek military police during the authoritarian regime that ended in 1974 (Haritos-Fatouros, 1988). A psychologist interviewed the men, identifying the steps used in training them to use torture in questioning prisoners. First, the men were ordered to stand guard outside the interrogation and torture cells. Then they stood guard inside the detention rooms, where they observed the torture of prisoners. Then they “helped” beat up prisoners. After they had obediently followed these orders and became actively involved, the torturers found their actions easier to carry out. Similar procedures have been used around the world to train military and police interrogators to use torture on political opponents and criminal suspects, although torture is expressly forbidden under international law (Conroy, 2000; Huggins, Haritos-Fatouros, & Zimbardo, 2003; Mayer, 2009).

From their standpoint, torturers justify their actions because they see themselves as “good guys” who are just “doing their jobs,” especially in wartime. And perhaps they are—but such a justification overlooks entrapment. This prisoner might be a murderer or a terrorist, but what if this other one is completely innocent? Before long, the torturer has shifted his reasoning from “If this person is guilty, he deserves to be tortured” to “If I am torturing this person, he must be guilty—and besides, if I am doing it, it isn't torture.” And so the abuse escalates (Tavris & Aronson, 2007).

This is a difficult concept for people who divide the world into “good guys” versus “bad guys” and cannot imagine that good guys might do brutal things; if the good guys are doing it, by definition, it's all right to do. Yet in everyday life, as in the Milgram study, people often set out on a path that is morally ambiguous, only to find that they have traveled a long way toward violating their own principles. From Greece's torturers to the African nuns, from Milgram's well-meaning volunteers to all of us in our everyday lives, from cheating on exams to cheating in business, people face the difficult task of drawing a line beyond which they will not go. For many, the demands of the role and the social pressures of the situation defeat the inner voice of conscience.