8.2

Social Influences on Beliefs and Behavior

Social psychologists are interested not only in what people do in social situations, but also in what is going on in their heads while they are doing it. Those who study social cognition examine how people's perceptions of themselves and others affect their relationships and also how the social environment influences their perceptions, beliefs, and values. Current approaches draw on evolutionary theory, neuroimaging studies, surveys, and experiments to identify universal themes in how human beings perceive and feel about one another. In this section, we will consider two important topics in social cognition: attributions and attitudes.

Attributions

A detective's job is to find out who did the dirty deed, but most of us also want to know why people do bad things. Was it because of a terrible childhood, a mental illness, possession by a demon, or what? According to attribution theory, the explanations we make of our behavior and the behavior of others generally fall into two categories. When we make a situational attribution, we are identifying the cause of an action as something in the situation or environment: “Joe stole the money because his family is starving.” When we make a dispositional attribution, we are identifying the cause of an action as something in the person: “Joe stole the money because he is a born thief.”

When people are trying to explain someone else's behavior, they tend to overestimate personality traits and underestimate the influence of the situation (Forgas, 1998; Gilbert & Malone, 1995; Nisbett & Ross, 1980). In terms of attribution theory, they tend to ignore situational attributions in favor of dispositional ones. This tendency has been called the fundamental attribution error (Jones, 1990).

The Fundamental Attribution Error

Were the hundreds of people who obeyed Milgram's experimenters sadistic by nature? Were the student guards in the prison study cruel and the prisoners cowardly by temperament? Were the individuals who pocketed the money from a mailbox on a dirty street “born thieves”? Those who think so are committing the fundamental attribution error. The impulse to explain other people's behavior in terms of their personalities is so strong that we do it even when we know that the other person was required to behave in a certain way (Yzerbyt et al., 2001).

The fundamental attribution error is especially prevalent in Western nations, where middle-class people tend to believe that individuals are responsible for their own actions and dislike the idea that the situation has much influence over them. Therefore, they prefer to explain behavior in terms of people's traits (Na & Kitayama, 2011). They think that they would have refused the experimenter's cruel orders and they would have treated fellow-students-temporarily-called-prisoners fairly. In contrast, in countries such as India, where everyone is embedded in caste and family networks, and in Japan, China, Korea, and Hong Kong, where people are more group oriented than in the West, people are more likely to be aware of situational constraints on behavior, including their own behavior (Balcetis, Dunning, & Miller, 2008; Choi et al., 2003). Thus, if someone is behaving oddly, makes a mistake, or commits an ethical lapse, a person from India or China, unlike a Westerner, is more likely to make a situational attribution of the person's behavior (“He's under pressure”) than a dispositional one (“He's incompetent”).

A primary reason for the fundamental attribution error is that people rely on different sources of information to judge their own behavior and that of others. We know what we ourselves are thinking and feeling, but we can't always know the same of others. Thus, we assess our own actions by introspecting about our feelings and intentions, but when we observe the actions of others, we have only their behavior to guide our interpretations (Pronin, 2008; Pronin, Gilovich, & Ross, 2004). This basic asymmetry in social perception is further widened by self-serving biases, habits of thinking that make us feel good about ourselves, even (perhaps especially) when we shouldn't. Here are three types of self-serving biases that are especially relevant to the attributions that people often make:

The bias to choose the most flattering and forgiving attributions of our own lapses. When it comes to explaining their own behavior, people tend to choose attributions that are favorable to them, taking credit for their good actions (a dispositional attribution) but letting the situation account for their failures, embarrassing mistakes, or harmful actions (Mezulis et al., 2004). For instance, most North Americans, when angry, will say, “I am furious for good reason; this situation is intolerable.” They are less likely to say, “I am furious because I am an ill-tempered grinch.” On the other hand, if they do something admirable, such as donating to charity, they are likely to attribute their motives to a personal disposition (“I'm so generous”) instead of the situation (“That guy on the phone pressured me into it”).

The bias that we are better, smarter, and kinder than others. This one has been called the “self-enhancement” bias or the “better-than-average” effect. It describes the tendency of most people to think they are much better than their peers on many valued dimensions: more virtuous, honorable, and moral; more competent; more compassionate and generous (Balcetis, Dunning, & Miller, 2008; Brown, 2012; Dunning et al., 2003; Loughnan et al., 2011). They overestimate their willingness to do the right thing in a moral dilemma, give to a charity, cooperate with a stranger in trouble, and so on. But when they are actually in a situation that calls for generosity, compassion, or ethical action, most people fail to live up to their own inflated self-image because the demands of the situation have a stronger influence than good intentions. This bias even occurs among people who literally strive to be “holier than thou” and “humbler than thee” for religious reasons (Rowatt et al., 2002). In two studies conducted at fundamentalist Christian colleges, the greater the students' intrinsic religiosity and fundamentalism, the greater was their tendency to rate themselves as being more adherent to biblical commandments than other people—and more humble than other people, too!

The bias to believe that the world is fair. According to the just-world hypothesis, attributions are also affected by the need to believe that justice usually prevails, that good people are rewarded and bad guys punished (Lerner, 1980). When this belief is thrown into doubt—especially when bad things happen to “good people” who are just like us—we are motivated to restore it (Aguiar et al., 2008; Hafer & Rubel, 2015). Unfortunately, one common way of restoring the belief in a just world is to call upon a dispositional attribution called blaming the victim: Maybe that person wasn't so good after all; he or she must have done something to deserve what happened or to provoke it. Blaming the victim is virtually universal when people are ordered to harm others or find themselves entrapped into harming others (Bandura, 1999). In the Milgram study, some “teachers” made comments such as “[The learner] was so stupid and stubborn he deserved to get shocked” (Milgram, 1974).

It is good for our self-esteem to feel that we are kinder, more competent, and more moral than other people, and to believe that we are not influenced by external circumstances (except when they excuse our mistakes). But these flattering delusions can distort communication, impede the resolution of conflicts, and lead to serious misunderstandings.

Of course, sometimes dispositional attributions do explain a person's behavior. The point to remember is that the attributions you make can have huge consequences. For example, happy couples usually attribute their partners' occasional thoughtless lapses to something in the situation (“Poor guy is under a lot of stress”) and their partners' loving actions to a stable, internal disposition (“He has the sweetest nature”). But unhappy couples do just the reverse. They attribute lapses to their partners' personalities (“He is totally selfish”) and good behavior to the situation (“Yeah, he gave me a present, but only because his mother told him to”) (Karney & Bradbury, 2000). You can see why the attributions you make about your partner, your parents, and your friends will affect how you get along with them—and how long you will put up with their failings.

Reviewing the Attribution Process

Attitudes

People hold attitudes about all sorts of things—politics, food, children, movies, sports heroes, you name it. An attitude is a belief about people, groups, ideas, or activities. Some attitudes are explicit: We are aware of them, they shape our conscious decisions and actions, and they can be measured on self-report questionnaires. Others are implicit: We are unaware of them, they may influence our behavior in ways we do not recognize, and they are measured in indirect ways (Stanley, Phelps, & Banaji, 2008).

Cognitive Dissonance Some of your attitudes change when you have new experiences, and on occasion they change because you rationally decide you were wrong about something. But attitudes also change because of the psychological need for consistency and the mind's normal biases in processing information. In Chapter9, we will discuss cognitive dissonance, the uncomfortable feeling that occurs when two attitudes, or an attitude and a behavior, are in conflict (are dissonant). To resolve this dissonance, most people will change one of their attitudes. If a politician or celebrity you admire does something stupid, immoral, or illegal, you can restore consistency either by lowering your opinion of the person or by deciding that the person's behavior wasn't so stupid or immoral after all.

Here's an example closer to home: cheating. Let's say two students have the same general attitude toward it: It's not an ideal way to get ahead, but it's not the greatest crime, either (see Figure8.2a). Now they take an important exam and freeze on a crucial question. They have a choice: Read their neighbor's answers and cheat (to get a better grade) or refrain from doing so (to maintain feelings of integrity). Impulsively, one cheats; the other doesn't (see Figure8.2b). What happens now? The answer is illustrated in Figure8.2c. To reduce dissonance, each one will justify their action to make it consonant with their beliefs. The one who refrained will begin to think that cheating is serious after all, that it harms everyone, and that cheaters should be punished (“Hey! Expel them!”). But the one who cheated will need to resolve the dissonance between “I am a fine, honest human being” and “I just cheated.” He or she could say, “I guess I'm not an honest person after all,” but it is more likely that the person will instead decide that cheating isn't very serious (“Hey! Everyone does it!”).

Figure 8.2

The Slippery Slope of Self-Justification

Understanding how cognitive dissonance works to keep our beliefs and behavior in harmony is important because the way we reduce dissonance can have major, unexpected consequences. The student who cheated “just this once” will find it easier to cheat again on an assignment, and then again by turning in a term paper written by someone else, sliding down the slippery slope of entrapment. By the time the cheater has slid to the bottom, it will be extremely difficult to go back up because that would mean admitting “I was wrong; I did a bad thing.” That is how a small act of dishonesty, corruption, or error—from cheating to staying in a bad relationship—can set a person on a course of action that becomes increasingly self-defeating, cruel, or foolhardy . . . and difficult to reverse (Tavris & Aronson, 2007).

Unfortunately for critical thinking, people often restore cognitive consistency by dismissing evidence that might otherwise throw their fundamental beliefs into question (Aronson, 2012). In fact, they often become even more committed to a discredited belief. In one study, when people were thrown into doubt about the rightness of a belief or their position on some issue that was very important to them—such as being a vegetarian or carnivore—they reduced dissonance by advocating their original position even more strongly. As the researchers summarized, “When in doubt, shout!” (Gal & Rucker, 2010). This mechanism explains why people in religious cults that have invested heavily in failed doomsday predictions rarely say, “What a relief that I was wrong.” Instead, many become even more committed proselytizers (Festinger, Riecken, & Schachter, 1956). To learn more about the process of cognitive dissonance, watch the video Changing Attitudes and Behavior 1.

Watch

Changing Attitudes and Behavior 1

Shifting Opinions and Bedrock Beliefs All around you, every day, advertisers, politicians, and friends are trying to influence your attitudes. One weapon they use is the drip, drip, drip of a repeated idea (Lee, Ahn, & Park, 2015). Repeated exposure even to a nonsense syllable such as zug is enough to make a person feel more positive toward it (Zajonc, 1968). The familiarity effect, the tendency to hold positive attitudes toward familiar people or things, has been demonstrated across cultures, across species, and across states of awareness, from alert to preoccupied. It works even for stimuli you aren't aware of seeing (Monahan, Murphy, & Zajonc, 2000). A related phenomenon is the validity effect, the tendency to believe that something is true simply because it has been repeated many times. Repeat something often enough, even the basest lie, and eventually the public will believe it. Hitler's propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, called this technique the “Big Lie.”

In a series of experiments, Hal Arkes and his associates demonstrated how the validity effect operates (Arkes, 1993; Arkes, Boehm, & Xu, 1991). In a typical study, people read a list of statements, such as “Mercury has a higher boiling point than copper” or “Over 400 Hollywood films were produced in 1948.” They had to rate each statement for its validity, on a scale of 1 (definitely false) to 7 (definitely true). A week or two later, they again rated the validity of some of these statements and also rated others that they had not seen previously. The result: Mere repetition increased the perception that the familiar statements were true. The same effect also occurred for other kinds of statements, including unverifiable opinions (e.g., “At least 75 percent of all politicians are basically dishonest”), opinions that subjects initially felt were true, and even opinions they initially felt were false. “Note that no attempt has been made to persuade,” said Arkes (1993). “No supporting arguments are offered. We just have subjects rate the statements. Mere repetition seems to increase rated validity. This is scary.”

On most everyday topics, such as movies, sports, and the boiling point of mercury, people's attitudes range from casual to committed. If your best friend is neutral about baseball whereas you are an insanely devoted fan, your friendship will probably survive. But when the subject is one involving beliefs that give meaning and purpose to a person's life—most notably, politics and religion—it's another ball game, so to speak. Wars have been fought, and are being fought as you read this, over people's most passionate convictions. Perhaps the attitude that causes the most controversy and bitterness around the world is the one toward religious diversity: accepting or intolerant. Some people of all religions accept a world of differing religious views and practices; they believe that church and state should be separate. But for many fundamentalists in any religion, religion and politics are inseparable; they believe that one religion should prevail (Jost et al., 2003). You can see, then, why these irreconcilable attitudes cause continuing conflict, and sometimes are used to justify terrorism and war. Why are people so different in these views? Why are people so different in these views? Watch Changing Attitudes and Behavior 2 to learn what an expert in this field has to say about this issue.

Watch

Changing Attitudes and Behavior 2

Persuasion or “Brainwashing”? The Case of Suicide Bombers

LO 8.2.C Summarize four elements that contribute to indoctrination.

Listen to the Audio

Let's now see how the social-psychological factors discussed thus far might help explain the disturbing phenomenon of suicide bombers. In many countries, young men and women have wired themselves with explosives and blown up soldiers, civilians, and children, sacrificing their own lives in the process. Although people on two sides of a war dispute the definition of terrorism—one side's “terrorist” is the other side's “freedom fighter”—most social scientists define terrorism as politically motivated violence specifically designed to instill feelings of terror and helplessness in a population (Moghaddam, 2005; Roberts, 2015). Are these perpetrators mentally ill? Have they been “brainwashed”?

“Brainwashing” implies that a person has had a sudden change of mind without being aware of what is happening; it sounds mysterious and strange. On the contrary, the methods used to create a terrorist suicide bomber are neither mysterious nor unusual (Bloom, 2005; Moghaddam, 2005). Some people may be more emotionally vulnerable than others to these methods, but most of the people who become terrorists are not easily distinguishable from the general population. Indeed, most of them had no psychopathology and were often quite educated and affluent (Krueger, 2007; Sageman, 2008; Silke, 2003). Rather than defining themselves as terrorists, they saw themselves as committing “self-sacrificing violence for the greater good”; and far from being seen as crazy loners, most suicide bombers are celebrated by their families and communities for their “martyrdom.” This social support enhances their commitment to the cause (Bloom, 2005; Ginges & Atran, 2011). The methods of indoctrination that lead to that commitment include these elements:

The person is subjected to entrapment. Just as ordinary people do not become torturers overnight, they do not become terrorists overnight either; the process proceeds step by step. At first, the new recruit to the cause agrees only to do small things, but gradually the demands increase to spend more time, spend more money, make more sacrifices. Like other revolutionaries, people who become suicide bombers are idealistic and angry about injustices, real and perceived. But some ultimately take extreme measures because, over time, they have become entrapped in closed groups led by strong or charismatic leaders (Moghaddam, 2005).

The person's problems, personal and political, are explained by one simple attribution, repeatedly emphasized: “It's all the fault of those bad people; we have to eliminate them.”

The person is offered a new identity and is promised salvation. The recruit is told that he or she is part of the chosen, the elite, or the saved. In 1095, Pope Urban II launched a holy war against Muslims, assuring his forces that killing a Muslim was an act of Christian penance. Anyone killed in battle, the pope promised, would bypass thousands of years of torture in purgatory and go directly to heaven. This is what young Muslim terrorists are promised today for killing Western “infidels.”

The person's access to disconfirming (dissonant) information is severely controlled. As soon as a person is a committed believer, the leader limits the person's choices, denigrates critical thinking, and suppresses private doubts. Recruits may be physically isolated from the outside world and thus from antidotes to the leader's ideas. They are separated from their families, are indoctrinated and trained for 18 months or more, and eventually become emotionally bonded to the group and the leader (Atran, 2010).

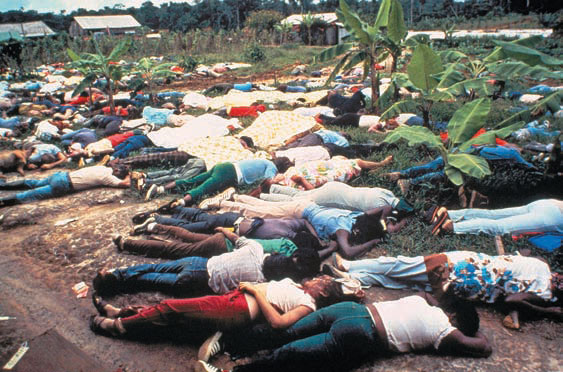

More than 900 members of the People’s Temple committed mass suicide at the instigation of their leader, Jim Jones.

These methods are similar to those that have been used to entice Americans into religious and other sects (Ofshe & Watters, 1994; Singer, 2003). In the 1970s, cult leader Jim Jones told the more than 900 members of his “People's Temple” that the time had come to die, and they dutifully lined up to drink a Kool-Aid-like drink mixed with cyanide; parents gave it first to their infants and children. (The legacy of that massacre is the term “drinking the Kool-Aid,” which refers to a person or group's unquestioning belief in an ideology that could lead to their death.) In the 1990s, David Koresh, leader of the Branch Davidian cult near Waco, Texas, led his followers to a fiery death in a shootout with the FBI. In these groups, as in the case of terrorist cells, most recruits started out as ordinary people, but after being subjected to the techniques we have described, they ended up doing things that they previously would have found unimaginable. Social psychologists can explain the extremes of persuasion found in terrorism, “brainwashing,” and cult activity. Fortunately, they can also explain the mechanisms at work during more mundane examples of persuasion. Watch the video Persuasion to learn more about attitude change tactics.

Watch

Persuasion