9.1

Thought: Using What We Know

In 2011, when an IBM computer named Watson defeated two very smart human beings on Jeopardy, the world was abuzz about whether that meant that machines would finally outthink people. But cognitive scientists were quick to point out that the human mind is actually far more complex than a computer; the machines have yet to learn to make puns and jokes, acquire an immediate insight into another person's feelings, or write a play or book. Nonetheless, parallels between mind and machine can be useful guides to thinking about cognition because both actively process information by altering it, organizing it, and using it to make decisions. Just as computers internally manipulate representations of 0s and 1s to “think,” so we mentally manipulate internal representations of objects, activities, and situations. For a preview of these processes, watch the video I Am, Therefore I Think.

Watch

I Am, Therefore I Think

The Elements of Cognition

One type of mental representation is the concept, a mental category that groups objects, relations, activities, abstractions, or qualities having common properties. The instances of a concept are seen as roughly similar: golden retriever, cocker spaniel, and border collie are instances of the concept dog; and anger, joy, and sadness are instances of the concept emotion. Concepts simplify and summarize information about the world so that it is manageable and so that we can make decisions quickly and efficiently. You may never have seen a basenji or eaten escargots, but if you know that the first is an instance of dog and the second an instance of food, you will know, roughly, how to respond (unless you do not like to eat snails, which is what escargots are).

Basic concepts have a moderate number of instances and are easier to acquire than those having either few or many instances (Rosch, 1973). What is the object pictured here? You will probably call it an apple. The concept apple is more basic than fruit, which includes many more instances and is more abstract. It is also more basic than Braeburn apple, which is quite specific. Children seem to learn basic-level concepts earlier than other concepts, and adults use basic concepts more often than other concepts because basic concepts convey an optimal amount of information in most situations.

What is this?

The qualities associated with a concept do not necessarily all apply to every instance: Some apples are not red; some dogs do not bark; some birds do not fly. But all the instances of a concept do share a family resemblance. When we need to decide whether something belongs to a concept, we are likely to compare it to a prototype, a representative instance of the concept (Rosch, 1973). Which dog is doggier, a golden retriever or a Chihuahua? Which fruit is more fruitlike, an apple or a pineapple? Which activity is more representative of sports, football or weightlifting? Most people within a culture can easily tell you which instances of a concept are most representative, or prototypical.

Some instances of a concept are more representative or prototypical than others. A “bachelor” is an unmarried man. Is John Mayer a bachelor, even though he is often romantically linked to different women for years at a time? Is the Pope a bachelor? What about Elton John, who married his long-time male partner David Furnish in Britain in 2014 but whose marriage would not have been recognized in some American states at the time?

The words used to express concepts may influence or shape how we think about them. Many decades ago, Benjamin Lee Whorf, an insurance inspector by profession and a linguist and anthropologist by inclination, proposed that language molds cognition and perception. According to Whorf (1956), because English has only one word for snow and Eskimos (the Inuit) have many (for powdered snow, slushy snow, falling snow . . .), the Inuit notice differences in snow that English speakers do not. He also argued that grammar—the way words are formed and arranged to convey tense and other concepts—affects how we think about the world.

Whorf's theory was popular for a while and then fell from favor. After all, English speakers can see all those Inuit kinds of snow and they have plenty of adjectives to describe the different varieties. But Whorf's ideas have once again gained attention. Vocabulary and grammar do affect how we perceive the location of objects, think about time, attend to shapes and colors, and remember events (Boroditsky, 2003; Gentner & Goldin-Meadow, 2003; Gentner et al., 2013). A language spoken by a group in Papua, New Guinea, refers to blue and green with one word, but to distinct shades of green with two separate words. On perceptual discrimination tasks, New Guineans who speak this language handle green contrasts better than blue–green ones, whereas the reverse holds true for English speakers (Roberson, Davies, & Davidoff, 2000). Similar results on the way language affects color perception have been obtained in studies comparing English with certain African languages (Özgen, 2004; Roberson, Davidoff, Davies, & Shapiro, 2005).

How do you divide up these hues? People who speak a language that has only one word for blue and green, but separate words for shades of green, handle green contrasts better than the blue–green distinction. English speakers do the opposite.

Here's another example: In many languages, speakers must specify whether an object is linguistically masculine or feminine, as in Spanish, where la cuenta, the bill, is feminine but el cuento, the story, is masculine. It seems that labeling a concept as masculine or feminine affects the attributes that native speakers ascribe to it. Thus, a German speaker will describe a key (masculine in German) as hard, heavy, jagged, serrated, and useful, whereas a Spanish speaker is more likely to describe a key (feminine in Spanish) as golden, intricate, little, and lovely, shiny (Boroditsky, Schmidt, & Phillips, 2003). The video The Mind Is What the Brain Does reviews some of the elements of cognition.

Watch

The Mind Is What the Brain Does

Concepts are the building blocks of thought, but they would be of limited use if we merely stacked them up mentally. We must also represent their relationships to one another. One way we accomplish this may be by storing and using propositions, units of meaning that are made up of concepts and that express a unitary idea. A proposition can express nearly any sort of knowledge (“Rachael raises border collies”) or belief (“Border collies are smart”). Propositions, in turn, are linked together in complicated networks of knowledge, associations, beliefs, and expectations. These networks, which psychologists call cognitive schemas, serve as mental frameworks for describing and thinking about various aspects of the world. Gender schemas represent a person's beliefs and expectations about what it means to be male or female, and people also have schemas about cultures, occupations, animals, geographical locations, and many other features of the social and natural environment.

Mental images—especially visual images, or pictures in the mind's eye—are also important in thinking and in constructing cognitive schemas. Although no one can directly see another person's visual images, psychologists are able to study them indirectly. One method is to measure how long it takes people to rotate an image in their imaginations, scan from one point to another in an image, or read off some detail from an image. The results suggest that visual images behave much like images on a computer screen: We can manipulate them, they occur in a mental space of a fixed size, and small ones contain less detail than larger ones (Kosslyn, 1980; Shepard & Metzler, 1971). People often rely on visual images when they solve spatial or mechanical puzzles (Hegarty & Waller, 2005). Most people also report auditory images (such as a song, slogan, or poem you can hear in your “mind's ear”), and many report images in other sensory modalities as well—touch, taste, smell, or pain. Some even report kinesthetic images, imagined sensations in the muscles and joints.

Figure9.1 is a visual summary of the elements of cognition.

Figure 9.1 - The Elements of Cognition

How Conscious Is Thought?

When we think about thinking, we usually have in mind those mental activities that are carried out in a deliberate way with a conscious goal in mind, such as solving a problem, drawing up plans, or making calculated decisions. However, much mental processing is not conscious.

Subconscious Thinking Some cognitive processes lie outside of awareness but can be brought into consciousness with a little effort when necessary. These subconscious processes allow us to handle more information and to perform more complex tasks than if we depended entirely on conscious processing. Indeed, many automatic but complex routines are performed “without thinking,” though they might previously have required careful, conscious attention: knitting, typing, driving a car, decoding the letters in a word in order to read it.

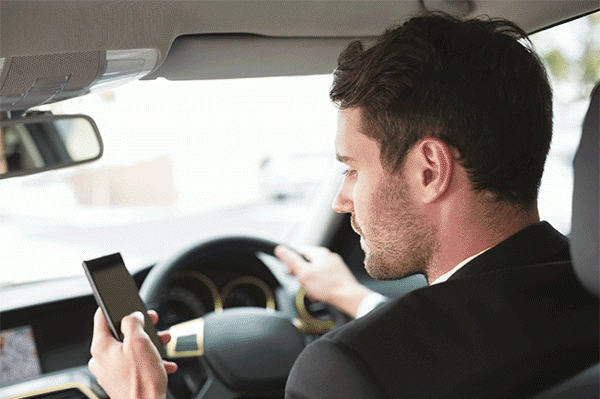

Because of the capacity for automatic processing, people can eat lunch while reading a book or drive a car while listening to music; in such cases, one of the tasks has become automatic. However, this does not mean you should go ahead and text your friends while driving. That's multitasking, and multitasking rarely works well. In fact, far from saving time, toggling between two or more tasks that require attention increases the time required to complete them (and in the case of driving and texting, is extremely dangerous). In addition, stress goes up, errors increase, reaction times lengthen, and memory suffers (Lien, Ruthruff, & Johnston, 2006). In one recent example, a commuter train's engineer violated company policy by texting while on the job, and he never saw an oncoming freight train. The resulting collision killed 25 people, including the engineer himself.

Some well-learned skills do not require much conscious thought and can be performed while doing other things, but multitasking can also get you into serious trouble. It’s extremely dangerous to text and drive at the same time.

Even overhearing one side of someone else's cell phone conversation siphons your attention away from a task you are doing, possibly because of the effort required to make sense of just one half of a conversation. In one experiment, when people listened to a “halfalogue” while they were doing a visual task, they made more than six times as many errors on the task than when they listened to an ordinary two-person conversation (Emberson et al., 2010). As for multitasking when you are the person talking on the phone, that can be hazardous to your health. Cell phone use greatly impairs a person's ability to drive, whether the phone is hands-free or not; a driver's attention is diverted far more by a phone conversation than by listening to music (Briggs, Hole, & Land, 2011; Strayer & Drews, 2007). Other distractions are equally dangerous. Drivers have been caught on camera checking their stocks, applying makeup, flossing their teeth, and putting in contact lenses—all while hurtling down the highway at high speeds (Klauer et al., 2006). Although we'd like to believe we have the unlimited cognitive capacity to take on more and more tasks simultaneously, ample evidence suggests otherwise.

Nonconscious Thinking Other kinds of thought processes, nonconscious processes, remain outside of awareness, even when you try to bring them back. As we will see shortly, people often find the solution to a problem when it suddenly pops into mind after they have given up trying to figure it out. And sometimes people learn a new skill without being able to explain how they perform it. For instance, they may discover the best strategy for winning at a card game without ever being able to consciously identify what they are doing (Bechara et al., 1997). With such implicit learning, you learn a rule or an adaptive behavior, either with or without a conscious intention to do so; but you don't know how you learned it, and you can't state, either to yourself or to others, exactly what it is you have learned (Frensch & Rünger, 2003; Lieberman, 2000). Many of our abilities, from speaking our native language properly to walking up a flight of stairs, are the result of implicit learning. But implicit learning is not always helpful because it can also generate biases and prejudices. We can learn an association between “stupidity” and “those people” without ever being aware of how we learned it or who taught it to us.

Even when our thinking is conscious, often we are not thinking very hard. We may act, speak, and make decisions out of habit, without stopping to analyze what we are doing or why we are doing it. Mindlessness—mental inflexibility, inertia, and obliviousness to the present context—keeps people from recognizing when a change in a situation requires a change in behavior. In a classic study of mindlessness, a psychologist approached people as they were about to use a photocopier and made one of three requests: “Excuse me, may I use the copy machine?” “Excuse me, may I use the copy machine, because I have to make copies?” or “Excuse me, may I use the copy machine, because I'm in a rush?” Normally, people will let someone go before them only if the person has a legitimate reason, as in the third request. In this study, however, people also complied when the reason sounded like an authentic explanation but was actually meaningless (“because I have to make copies”). They heard the form of the request but they did not hear its content, and they mindlessly stepped aside (Langer, Blank, & Chanowitz, 1978).

Problem Solving and Decision Making

Conscious and nonconscious processes are both involved in solving problems. In well-defined problems, the nature of the problem is clear (“I need more cookies for the party tomorrow”). Often, all you need to do to solve the problem is apply the right algorithm, a set of procedures guaranteed to produce a correct (or a best) solution even if you do not understand why it works. To increase a cookie recipe, for example, you can simply multiply the number of cookies you want per person by the number of people you need to feed. If the original recipe produced 10 cookies and you need 40, you can then multiply each ingredient by four. The recipe itself is also an algorithm (add flour, stir lightly, add raisins . . .), though you probably won't know the chemical changes involved when you combine the ingredients and heat the batter in an oven.

Other problems are fuzzier. There is no specific goal (“What should I have for dinner tomorrow?”) and no clearly correct solution, so no algorithm applies. In such cases, you may resort to a heuristic, a rule of thumb that suggests a course of action without guaranteeing an optimal solution (“Maybe I'll browse through some recipes online, or go to the market and see what catches my eye”). Many heuristics, like those used when playing chess, help you limit your options to a manageable number of promising ones, reducing the cognitive effort it takes to arrive at a decision (Galotti, 2007; Galotti, Wiener, & Tandler, 2014). Heuristics are useful to a student trying to choose a major, an investor trying to predict the stock market, a doctor trying to determine the best treatment for a patient, and a factory owner trying to boost production. All of them are faced with incomplete information with which to reach a solution, and may therefore resort to rules of thumb that have proven effective in the past.

Whether you are a chess grand master or just an ordinary person solving ordinary problems, you need to use heuristics, rules of thumb that help you decide on a strategy.

As useful as algorithms and heuristics are, sometimes the conscious effort to try to solve a problem seems to get you nowhere. Then, with insight, you suddenly see how to solve an equation or finish a puzzle without quite knowing how you found the solution. Insight probably involves different stages of mental processing (Bowers et al., 1990). First, clues in the problem automatically activate certain memories or knowledge. You begin to see a pattern or structure to the problem, although you cannot yet say what it is; possible solutions percolate in your mind. Although you are not aware of it, considerable mental work is guiding you toward a hypothesis, reflected in your brain as patterns of activity that differ from those associated with ordinary, methodical problem solving (Fields, 2011; Kounios & Beeman, 2009). Eventually, a solution springs to mind, seemingly from nowhere (“Aha, now I see!”).

People also say they sometimes rely on intuition—hunches and gut feelings—rather than conscious thinking when they make judgments or solve problems. Why do we trust such feelings? One possibility is that changes in our bodies signal that we are close to success. Long before people can consciously identify the best strategy for winning a card game, their bodies already seem to “know” it: Changes in their sweat and heart rate occur as soon as they make a wrong move (Bechara et al., 1997). What's more, people who are better at paying attention to their heart rates tend to be better at figuring out the best strategy (Dunn et al., 2010).

Should you therefore go with your gut or take your pulse when answering questions or solving problems on your next test? Not necessarily. Daniel Kahneman's book Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011) explains why. “Fast” thinking applies to our rapid, intuitive, emotional, almost automatic decisions; “slow” thinking requires intellectual effort. Naturally, most people rely on fast thinking because it saves time and effort, but it is often wrong. Here is one of his examples: Suppose that a bat and ball together cost $1.10 and that the bat costs one dollar more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? Most people answer with fast thinking and say 10 cents. But the correct answer is five cents. Think (slowly) about it.

Jerome Kagan (1989) once likened consciousness to firefighters who are quietly playing cards at the station house until an alarm goes off, calling them into action. Much of the time we rely on automatic processes and unconscious impressions to guide us through our daily tasks. Usually that's a good thing. Walking around in a state of fully conscious awareness would be impossible, and undesirable as well; we would never get anything done if we had to examine “thoughtfully” every little thing we do, say, decide, or overhear. But multitasking, mindlessness, and operating on automatic pilot can also lead to errors and mishaps, ranging from the trivial (misplacing your keys) to the serious (walking into traffic because you're texting). Therefore, most of us would probably benefit if our mental firefighters paid a little more attention to their jobs. How can we improve our capacity to reason rationally and think critically? We turn to that question next.

Reasoning Rationally

Reasoning is purposeful mental activity that involves operating on information to reach a conclusion. Unlike impulsive (“fast”) or nonconscious responding, reasoning requires us to draw specific inferences from observations, facts, or assumptions. In formal reasoning problems—the kind you might find, say, on an intelligence test or a college entrance exam—the information needed for drawing a conclusion or reaching a solution is specified clearly, and there is a single right (or best) answer. In informal reasoning problems, there is often no clearly correct solution. Many approaches, viewpoints, or possible solutions may compete, and you may have to decide which one is most “reasonable.”

To do this wisely, a person must be able to use dialectical reasoning, the process of comparing and evaluating opposing points of view to resolve differences. Philosopher Richard Paul (1984) once described dialectical reasoning as movement “up and back between contradictory lines of reasoning, using each to critically cross-examine the other.” Dialectical reasoning is what juries are supposed to do to arrive at a verdict: consider arguments for and against the defendant's guilt, point and counterpoint. It is also what voters are supposed to do when thinking about whether the government should raise or lower taxes, or about the best way to improve public education.

However, many adults have trouble thinking dialectically; they take one position, and that's that. When do people develop the ability to think critically—to question assumptions, evaluate and integrate evidence, consider alternative interpretations, and reach conclusions that can be defended as most reasonable?

One reason that Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker became world famous and has been much imitated is that it captures so perfectly the experience of thinking reflectively.

To find out, Patricia King and Karen Kitchener (1994, 2002, 2004) provided a large, diverse sample of adolescents and adults with statements describing opposing viewpoints on various topics. Each person then had to answer several questions, such as “What do you think about these statements?” “On what do you base your position?” and “Why do you suppose disagreement exists about this issue?” From the responses of thousands of participants, King and Kitchener identified several stations on the road to what they call reflective judgment and we have called critical thinking. At each one, people make different assumptions about how things are known and use different ways of justifying their beliefs.

In general, people who rely on prereflective thinking tend to assume that a correct answer always exists and that it can be obtained directly through the senses (“I know what I've seen”) or from authorities (“They said so on the news”; “That's what I was brought up to believe”). If authorities do not yet have the truth, prereflective thinkers tend to reach conclusions on the basis of what “feels right” at the moment. They do not distinguish between knowledge and belief or between belief and evidence, and they see no reason to justify a belief. One respondent, when asked about evolution, said, “Well, some people believe that we evolved from apes and that's the way they want to believe. But I would never believe that way and nobody could talk me out of the way I believe because I believe the way that it's told in the Bible.”

People who are quasi-reflective thinkers recognize that some things cannot be known with absolute certainty and that judgments should be supported by reasons, yet they pay attention only to evidence that fits what they already believe. They seem to think that because knowledge is uncertain, any judgment about the evidence is purely subjective. Quasi-reflective thinkers will defend a position by saying, “We all have a right to our own opinion,” as if all opinions are created equal. One college student, when asked whether one opinion on the safety of food additives was right and others were wrong, answered, “No. I think it just depends on how you feel personally because people make their decisions based on how they feel and what research they've seen. So what one person thinks is right, another person might think is wrong. . . . If I feel that chemicals cause cancer and you feel that food is unsafe without them, your opinion might be right to you and my opinion is right to me.”

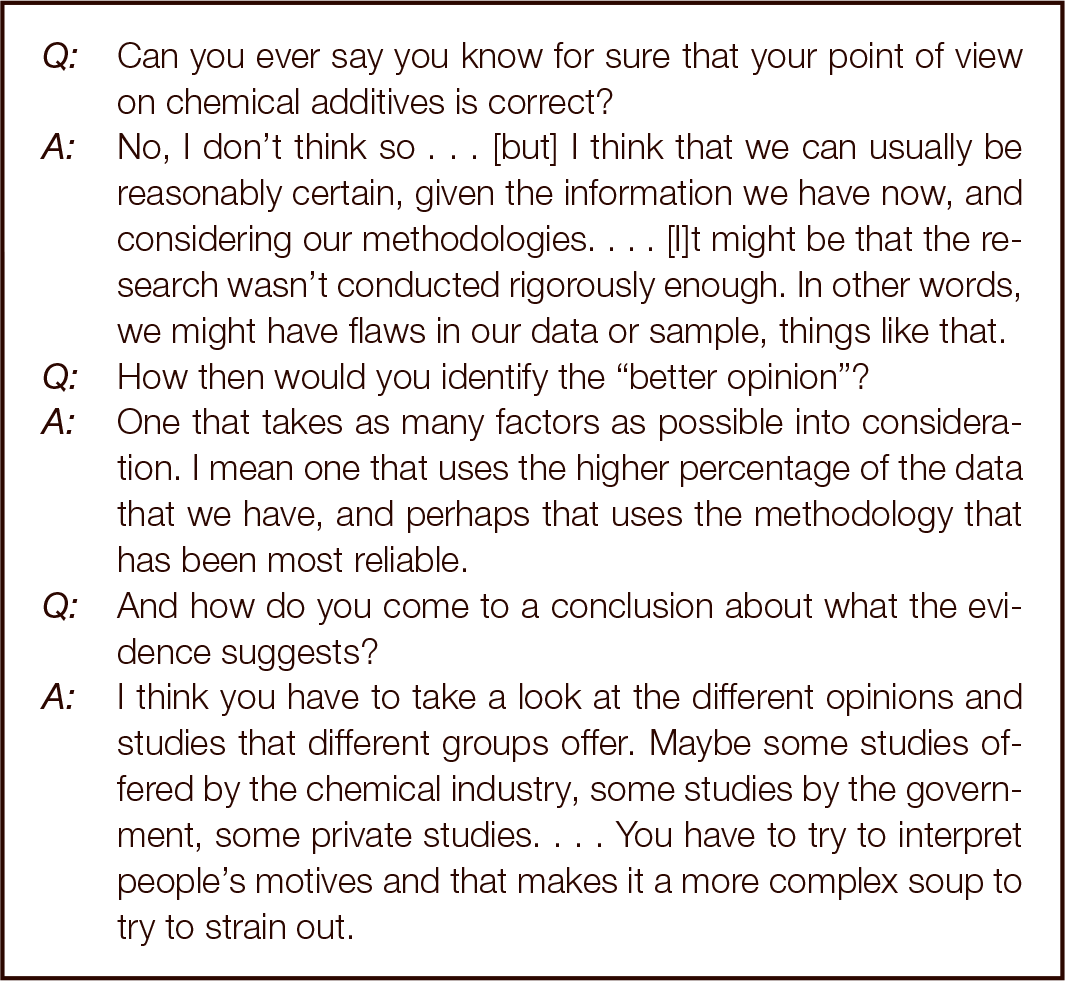

Finally, some people become capable of reflective judgment. They understand that although some things can never be known with certainty, some judgments are more valid than others because of their coherence, their fit with the available evidence, their usefulness, and so on. They are willing to consider evidence from a variety of sources and to reason dialectically. Figure9.2 shows an interview with a graduate student that illustrates reflective thinking.

Figure 9.2

Reflective Thinking

Here's an example of the process of reflective thinking. Notice how the discussants consider multiple perspectives and weigh the merits of the available evidence when reaching their conclusions.

Sometimes the types of judgments people make depend on the kind of problem or issue they are thinking about. They might be able to use reflective judgment for some issues yet be prereflective on others that hold deep emotional meaning for them (Haidt, 2012; King & Kitchener, 2004). But most people show no evidence of reflective judgment until their middle or late 20s, if ever. A longitudinal study found that many college students graduate without learning to distinguish fact from opinion, evaluate conflicting reports objectively, or resist emotional statements and political posturing (Arum & Roksa, 2011). Still, there's reason for hope. When college students get ample support for thinking reflectively, have opportunities to practice it in their courses, and apply themselves seriously to their studies, their thinking tends to become more complex, sophisticated, and well grounded (Kitchener et al., 1993). You can see why, in this book, we emphasize thinking about psychological findings, and not just memorizing them.