9.2

Barriers to Reasoning Rationally

Although most people have the capacity to think logically, reason dialectically, and make judgments reflectively, it is clear that they do not always do so. One obstacle is the need to be right; if your self-esteem depends on winning arguments, you will find it hard to listen with an open mind to competing views. Other obstacles include limited information and a lack of time to reflect carefully. But human thought processes are also tripped up by many predictable, systematic biases and errors. Psychologists have studied dozens of them (Kahneman, 2003, 2011). Here we describe just a few.

Exaggerating the Improbable (and Minimizing the Probable)

One common bias is the inclination to exaggerate the probability of rare events. This bias helps to explain why so many people enter lotteries and buy disaster insurance, and why some irrational fears persist. Evolution has equipped us to fear certain natural dangers, such as snakes. However, in modern life, many of these dangers are no longer much of a threat; the risk of a renegade rattler sinking its fangs into you in Chicago or New York is very low! Yet the fear lingers on, so we overestimate the danger. Evolution has also given us brains that are terrific at responding to an immediate threat or to acts that provoke moral outrage even though they pose no threat to the survival of the species (e.g., flag burning). Unfortunately, our brains were not designed to become alarmed by serious future threats that do not seem to pose much danger right now, such as global warming (Gilbert, 2006).

When judging probabilities, people are strongly influenced by the affect heuristic, the tendency to consult their emotions (affect) to judge the “goodness” or “badness” of a situation instead of judging probabilities objectively (Slovic & Peters, 2006; Slovic et al., 2002; Västfäll, Peters, & Slovic, 2014). Emotions can often help us make decisions by narrowing our options or by allowing us to act quickly in an uncertain or dangerous situation. But emotions can also mislead us by preventing us from accurately assessing risk. One unusual field study looked at how people in France responded to the “mad cow” crisis that occurred several years ago. (Mad cow disease affects the brain and can be contracted by eating meat from contaminated cows.) Whenever many newspaper articles reported the dangers of “mad cow disease,” beef consumption fell during the following month. But when news articles, reporting the same dangers, used the technical names of the disease—Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and bovine spongiform encephalopathy—beef consumption stayed the same (Sinaceur, Heath, & Cole, 2005). The more alarming labels caused people to reason emotionally and to overestimate the danger. (During the entire period of the supposed crisis, only six people in France were diagnosed with the disease.)

Because of the affect and availability heuristics, many of us overestimate the chances of suffering a shark attack. Shark attacks are extremely rare, but they are terrifying and easy to visualize.

Our judgments about risks are also influenced by the availability heuristic, the tendency to judge the probability of an event by how easy it is to think of instances of it (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). The availability heuristic often works hand in hand with the affect heuristic. Catastrophes and shocking accidents evoke an especially strong emotional reaction in us, and thus stand out in our minds, becoming more available mentally than other kinds of negative events. (An image of a “mad cow”—that sweet, placid creature running amok!—is highly “available.”) This is why people overestimate the frequency of deaths from tornadoes and underestimate the frequency of deaths from asthma, which occur dozens of times more often but do not make headlines. It is why news accounts of a couple of shark attacks make people fear that they are in the midst of a shark-attack epidemic, even though such attacks on humans are extremely rare.

Avoiding Loss

In general, people try to avoid or minimize the risk of incurring losses when they make decisions. That strategy is rational enough, but people's perceptions of risk are subject to the framing effect, the tendency for choices to differ depending on how they are presented. When a choice is framed as the risk of losing something, people will respond more cautiously than when the very same choice is framed as a potential gain. They will choose a ticket that has a 1 percent chance of winning a raffle over one that has a 99 percent chance of losing. Or they will rate a condom as effective when they are told it has a 95 percent success rate in protecting against the AIDS virus but not when they are told it has a 5 percent failure rate—which of course is exactly the same thing (Linville, Fischer, & Fischhoff, 1992).

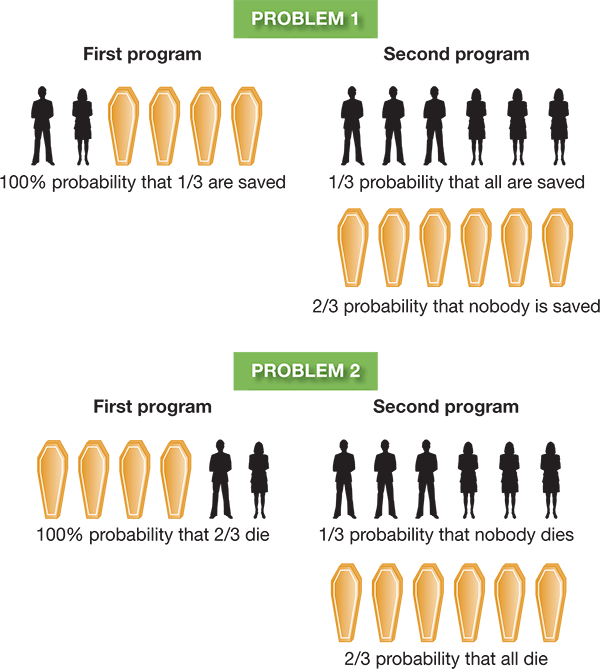

Suppose you had to choose between two health programs to combat a disease expected to kill 600 people. Which would you prefer: a program that will definitely save 200 people, or one with a one-third probability of saving all 600 people and a two-thirds probability of saving none? (Problem 1 in Figure9.3 illustrates this choice.) When asked this question, most people, including physicians, say they would prefer the first program. In other words, they reject the riskier though potentially more rewarding solution in favor of a sure gain. However, people will take a risk if they see it as a way to avoid loss. Suppose now that you have to choose between a program in which 400 people will definitely die and a program in which there is a one-third probability of nobody dying and a two-thirds probability that all 600 will die. If you think about it, you will see that the alternatives are exactly the same as in the first problem; they are merely worded differently (see Problem 2 in Figure9.3). Yet this time, most people choose the second solution. They reject risk when they think of the outcome in terms of lives saved, but they accept risk when they think of the outcome in terms of lives lost (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981).

Figure9.3

A Matter of Wording

The decisions we make can depend on how the alternatives are framed. When asked to choose between the two programs in Problem 1, which are described in terms of lives saved, most people choose the first program. When asked to choose between the programs in Problem 2, which are described in terms of lives lost, most people choose the second program. Yet the alternatives in the two problems are actually identical.

Few of us will have to face a decision involving hundreds of lives, but we may have to choose between different medical treatments for ourselves or a relative. Our decision may be affected by whether the doctor frames the choice in terms of chances of surviving or chances of dying.

Biases and Mental Sets

Relying on heuristics or being swayed by framing effects are just some of the barriers to reasoning rationally. Human thinkers also fall prey to a range of biases in the reasoning process. Let's look at some of these.

The Fairness Bias Imagine that you are playing a two-person game called the Ultimatum Game, in which your partner gets $20 and must decide how much to share with you. You can choose to accept your partner's offer, in which case you both get to keep your respective portions, or you can reject the offer, in which case neither of you gets a penny. How low an offer would you accept?

Actually, it makes sense to accept any amount at all, no matter how paltry, because then at least you will get something. But that is not how people respond when playing the Ultimatum Game. If the offer is too low, they are likely to reject it. In industrial societies, offers of 50 percent are typical and offers below 20 or 30 percent are commonly rejected, even when the absolute sums are large. In other societies, the amounts offered and accepted may be higher or lower, but there is always some amount that people consider unfair and refuse to accept (Güth & Kocher, 2014; Henrich et al., 2001). People may be competitive and love to win, but they are also powerfully swayed by a fairness bias, and motivated to see fairness prevail in these situations.

The Hindsight Bias

Listen to the Audio

There is a reason for the saying that hindsight is 20/20. When people learn the outcome of an event or the answer to a question, they are often sure that they “knew it all along.” Armed with the wisdom of hindsight, they see the outcome that actually occurred as inevitable, and they overestimate their ability to have predicted what happened beforehand (Fischhoff, 1975; Hawkins & Hastie, 1990). This hindsight bias shows up all the time in evaluating relationships (“I always knew they would break up”), medical judgments (“I could have told you that mole was cancerous”), and military opinions (“The generals should have known that the other side would attack”).

Perhaps you feel that we are not telling you anything new because you have always known about the hindsight bias. But then, you may just have a hindsight bias about the hindsight bias.

The Confirmation Bias When people want to make the most accurate judgment possible, they usually try to consider all of the relevant information. But when they are thinking about an issue they already feel strongly about, they often succumb to the confirmation bias, paying attention only to evidence that confirms their belief and finding fault with evidence that points in a different direction (Edwards & Smith, 1996; Nickerson, 1998). You rarely hear someone say, “Oh, thank you for explaining to me why my lifelong philosophy of childrearing (or politics, or investing) is wrong. I'm so grateful for the facts!” The person is more likely to say, “Oh, get lost, and take your crazy ideas with you.”

After you start looking for it, you will see the confirmation bias everywhere. Politicians brag about economic reports that confirm their party's position and dismiss counterevidence as biased or unimportant. Many jury members, instead of considering and weighing possible verdicts against the evidence, quickly construct a story about what happened and then consider only the trial evidence that supports their version of events. These same people are the most confident in their decisions and most likely to vote for an extreme verdict (Kuhn, Weinstock, & Flaton, 1994). We bet you can see the confirmation bias in your own reactions to what you are learning in psychology. In thinking critically, most of us apply a double standard; we think most critically about results we dislike. That is why the scientific method can be so difficult. It forces us to consider evidence that disconfirms our beliefs (see Figure9.4).

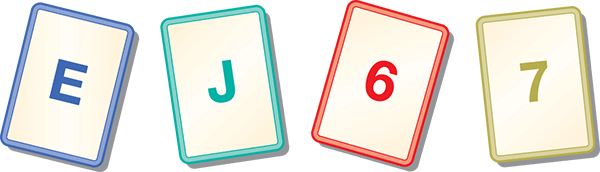

Figure 9.4

Confirming the Confirmation Bias

Suppose someone deals out four cards, each with a letter on one side and a number on the other. You can see only one side of each card, as shown here. Your task is to find out whether the following rule is true: “If a card has a vowel on one side, then it has an even number on the other side.” Which two cards do you need to turn over to find out? The majority of people say they would turn over the E and the 6, but they are wrong. You do need to turn over the E (a vowel), because if the number on the other side is even, it confirms the rule, and if it is odd, the rule is false. However, the card with the 6 tells you nothing. The rule does not say that a card with an even number must always have a vowel on the other side. Therefore, it doesn’t matter whether the 6 has a vowel or a consonant on the other side. The card you do need to turn over is the 7, because if it has a vowel on the other side, that fact disconfirms the rule. People do poorly on this problem because they are biased to look for confirming evidence and to ignore the possibility of disconfirming evidence.

Mental Sets Another barrier to rational thinking is the development of a mental set, a tendency to try to solve new problems by using the same heuristics, strategies, and rules that worked in the past on similar problems (see Figure9.5). Mental sets make human learning and problem solving efficient; because of them, we do not have to keep reinventing the wheel. But mental sets are not helpful when a problem calls for fresh insights and methods. They cause us to cling rigidly to the same old assumptions and approaches, blinding us to better or more rapid solutions.

One general mental set is the tendency to find patterns in events. This tendency is adaptive because it helps us understand and exert some control over what happens in our lives. But it also leads us to see meaningful patterns even when they do not exist. For example, many people with arthritis think that their symptoms follow a pattern dictated by the weather. They suffer more, they say, when the barometric pressure changes or when the weather is damp or humid. Yet when 18 arthritis patients were observed for 15 months, no association whatsoever emerged between weather conditions and the patients' self-reported pain levels, their ability to function in daily life, or a doctor's evaluation of their joint tenderness (Redelmeier & Tversky, 1996). Of course, because of the confirmation bias, the patients refused to believe the results.

Figure 9.5

Connect the Dots

The Need for Cognitive Consistency

LO 9.2.D Explain the process of cognitive dissonance, and describe three conditions under which feelings of cognitive dissonance are likely to occur.

Listen to the Audio

Mental sets and the confirmation bias cause us to avoid evidence that contradicts our beliefs. But what happens when disconfirming evidence finally smacks us in the face, and we cannot ignore or discount it any longer? As the 20th century rolled to an end, predictions of the end of the world escalated. Similar doomsday predictions have been made throughout history and continue today; after all, you are reading this despite the alleged Mayan prophecy that the world would end in December 2012. When these predictions fail, how come we never hear believers say, “Boy, what a fool I was”?

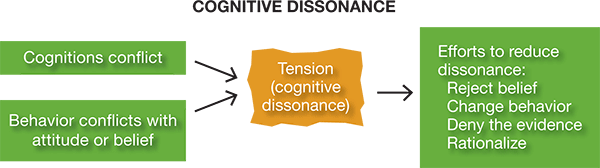

According to the theory of cognitive dissonance, people will resolve such conflicts in predictable, though not always obvious, ways (Festinger, 1957;). Dissonance, the opposite of consistency (consonance), is a state of tension that occurs when you hold either two cognitions (beliefs, thoughts, attitudes) that are psychologically inconsistent with one another, or a belief that is incongruent with your behavior. This tension is psychologically uncomfortable, so you will be motivated to reduce it. You may do this by rejecting or modifying one of those inconsistent beliefs, changing your behavior, denying the evidence, or rationalizing, as shown in Figure9.6.

Figure 9.6

The Process of Cognitive Dissonance

Years ago, in a famous field study, Leon Festinger and two associates explored people's reactions to failed prophecies by infiltrating a group of people who thought the world would end on December 21 (Festinger, Riecken, & Schachter, 1956). The group's leader, whom the social psychologists called Marian Keech, promised that the faithful would be picked up by a flying saucer and whisked to safety at midnight on December 20. Many of her followers quit their jobs and spent all their savings, waiting for the end to come. What would they do or say, Festinger and his colleagues wondered, to reduce the dissonance between “The world is still muddling along on the 21st” and “I predicted the end of the world and sold off all my worldly possessions”?

Festinger predicted that believers who had made no public commitment to the prophecy, who awaited the end of the world by themselves at home, would simply lose their faith. However, those who had acted on their conviction by selling their property and waiting with Keech for the spaceship would be in a state of dissonance. They would have to increase their religious belief to avoid the intolerable realization that they had behaved foolishly and others knew it. That is just what happened. At 4:45 a.m., long past the appointed hour of the saucer's arrival, the leader had a new vision. The world had been spared, she said, because of the impressive faith of her little band.

Cognitive dissonance theory predicts that in more ordinary situations as well, people will resist or rationalize information that conflicts with their existing ideas, just as the people in the arthritis study did. For example, cigarette smokers are often in a state of dissonance because smoking is dissonant with the fact that smoking causes illness. Smokers may try to reduce the dissonance by trying to quit, by rejecting evidence that smoking is bad, by persuading themselves that they will quit later on, by emphasizing the benefits of smoking (“A cigarette helps me relax”), or by deciding that they don't want a long life, anyhow (“It will be shorter but sweeter”).

You are particularly likely to reduce dissonance under three conditions (Aronson, 2012):

When you need to justify a choice or decision that you made freely. All car dealers know about buyer's remorse: The second that people buy a car, they worry that they made the wrong decision or spent too much, a phenomenon called postdecision dissonance. You may try to resolve this dissonance by deciding that the car you chose (or the toaster, or house, or spouse) is really, truly the best in the world. Before people make a decision, they can be open-minded, seeking information on the pros and cons of the choice at hand. After they make that choice, however, the confirmation bias will kick in, so that they will now notice all the good things about their decision and overlook or ignore evidence that they might have been wrong.

When you need to justify behavior that conflicts with your view of yourself. If you consider yourself to be honest, cheating will put you in a state of dissonance. To avoid feeling like a hypocrite, you will try to reduce the dissonance by justifying your behavior (“Everyone else does it”; “It's just this once”; “I had to do it to get into med school and learn to save lives”). Or if you see yourself as a kind person and you harm someone, you may reduce your dissonance by blaming the person you have victimized or by finding other self-justifying excuses.

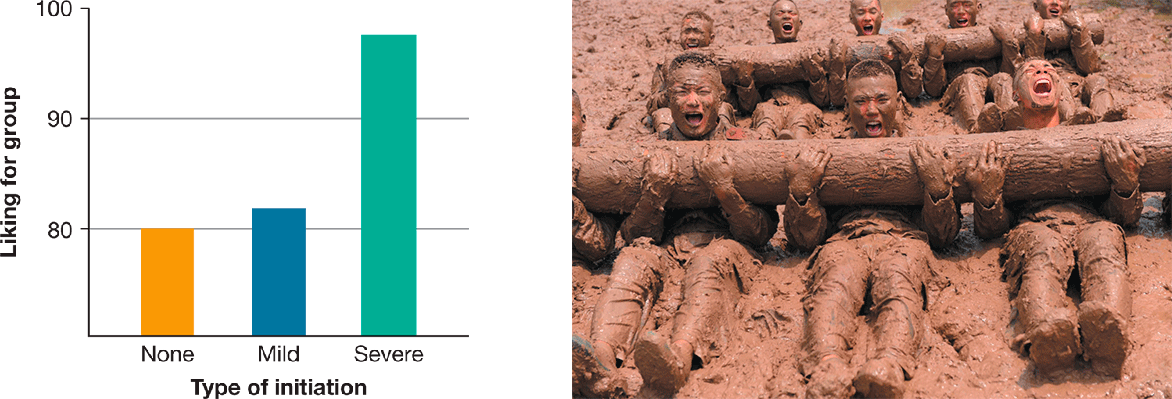

When you need to justify the effort put into a decision or choice. The harder you work to reach a goal, or the more you suffer for it, the more you will try to convince yourself that you value the goal, even if the goal turns out to be not so great after all (Aronson & Mills, 1959). This explains why hazing, whether in social clubs, on athletic teams, or in the military, turns new recruits into loyal members (see Figure9.7). The cognition “I went through a lot of awful stuff to join this group” is dissonant with the cognition “only to find I hate the group.” Therefore, people must decide either that the hazing was not so bad or that they really like the group. This mental reevaluation is called the justification of effort, and it is one of the most popular methods of reducing dissonance.

Figure 9.7

The Justification of Effort

The more effort you put into reaching a goal, the more highly you are likely to value it. As you can see in the graph on the left, after people listened to a boring group discussion, those who went through a severe initiation to join the group rated it most highly (Aronson & Mills, 1959). In the photo, soldiers undergo special and difficult training to join an elite unit. They will probably become extremely devoted members.

Some people are secure enough to own up to their mistakes instead of justifying them, and individuals and cultures vary in the kinds of experiences that cause them to feel dissonance. However, the need for cognitive consistency in those beliefs that are most central to our sense of self and our values is universal (Tavris & Aronson, 2007).

Overcoming Our Cognitive Biases

LO 9.2.E Discuss the conditions under which cognitive biases can be detrimental to reasoning, and when they might be beneficial.

Listen to the Audio

Sometimes our mental biases are a good thing. The ability to reduce cognitive dissonance helps us preserve our self-confidence and avoid sleepless nights second-guessing ourselves, and having a sense of fairness keeps us from behaving like self-centered louts. From this point of view, such biases are not so irrational after all. But our mental biases can also get us into trouble. The confirmation bias, the justification of effort, and a need to reduce postdecision dissonance permit people to stay stuck with decisions that eventually prove to be self-defeating, harmful, or incorrect. Physicians may continue using outdated methods, district attorneys may overlook evidence that a criminal suspect might be innocent, and managers may refuse to consider better business practices.

To make matters worse, most people have a “bias blind spot.” They acknowledge that other people have biases that distort reality, but they think that they themselves are free of bias and see the world as it really is (Pronin, Gilovich, & Ross, 2004; Ross, 2010). This blind spot is itself a bias, and it is a dangerous one because it can prevent individuals, nations, and ethnic or religious groups from resolving conflicts with others. Each side thinks that its own proposals for ending a conflict, or its own analyses of a problem, are reasonable and fair but the other side's are “biased.”

Fortunately, the situation is not entirely hopeless. For one thing, people are not equally irrational in all circumstances. When they are doing things in which they have some expertise or are making decisions that have serious personal consequences, their cognitive biases often diminish (Smith & Kida, 1991). Furthermore, after we understand a bias, we may, with some effort, be able to reduce or eliminate it, especially if we make an active, mindful effort to do so and take time to think carefully (Kida, 2006).

Some people, of course, seem to think more rationally than others a great deal of the time; we call them “intelligent.” Just what is intelligence, and how can we measure and improve it? We take up these questions next.