9.4

Dissecting Intelligence: The Cognitive Approach

Critics of standard intelligence tests point out that such tests tell us little about how a person goes about answering questions and solving problems. Nor do the tests explain why people with low scores often behave intelligently in real life, making smart consumer decisions, winning at the racetrack, and making wise choices in their relationships instead of repeating the same dumb patterns. Therefore, many scientists believe that the psychometric approach yields an incomplete picture of intelligence. Their aim is to identify the cognitive processes and strategies that people use when they are thinking and behaving intelligently.

Elements of Intelligence

One cognitive ingredient of intelligence is working memory, a complex capacity that enables you to manipulate information retrieved from long-term memory and interpret it appropriately for a given task. It permits you to juggle your attention while you are working on a problem, shifting your attention from one piece of information to another while ignoring distracting or irrelevant information. People who do well on tests of working memory tend to be good at many complex real-life tasks requiring the control of attention, including reading comprehension, writing, and reasoning (Engle, 2002). In contrast, people with less working-memory capacity often have trouble keeping their minds on the job at hand and do not get better on a task, even with practice (Kane et al., 2007). Instead of trying to help people do better on individual tasks, therefore, might it be possible to improve their working memories, and thereby improve a crucial component of intelligence? Some scientists have reported success with working-memory training programs (Klingberg, 2010). Unfortunately, more rigorous recent research suggests that although people do get better, with practice, at specific working-memory tests, those gains do not translate to better performance on other tests of working memory or intelligence (Redick et al., 2012).

Another cognitive ingredient of intelligence is metacognition, the knowledge or awareness of your own cognitive processes and the ability to monitor and control those processes. Students who are weak in metacognition fail to notice when a passage in a textbook is difficult, and they do not always realize that they haven't understood what they've been reading. As a result, they spend too little time on difficult material and too much time on material they already know. They are overconfident about their comprehension and memory, and are surprised when they do poorly on exams (Dunlosky & Lipko, 2007). In contrast, students who are strong in metacognition check their comprehension by restating what they have read, testing themselves, backtracking when necessary, and questioning what they are reading. When time is limited, they tackle fairly easy material (where the payoff will be great), and then move on to more difficult material; as a result, they learn better (Metcalfe, 2009).

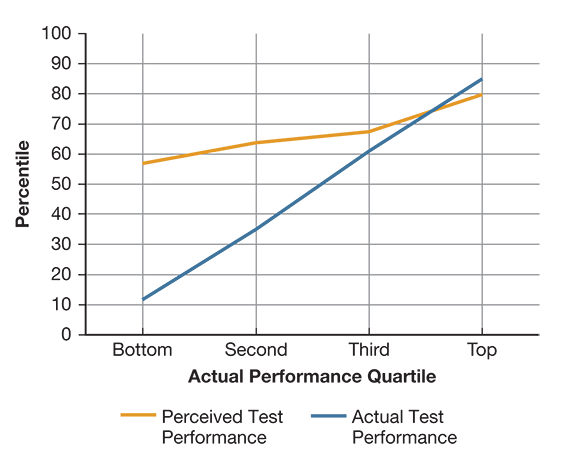

It works in the other direction, too: The kind of intelligence that enhances academic performance can also help you develop metacognitive skills. Students with poor academic skills typically fail to realize how little they know; they think they're doing fine (Dunning, 2005; Schlösser, Dunning, Johnson, & Kruger, 2013). The very weaknesses that keep them from doing well on tests or in their courses also keep them from realizing their weaknesses. In one study, students in a psychology course estimated how well they had just done on an exam relative to other students. As you can see in Figure9.11, those who had performed in the bottom quartile greatly overestimated their own performance (Dunning et al., 2003). In contrast, people with strong academic skills tend to be more realistic. Often, they even underestimate slightly how their performance compares with the performance of others.

Figure 9.11

Ignorance Is Bliss

In school and in other settings, people who perform poorly often have poor metacognitive skills and therefore fail to recognize their own lack of competence. As you can see, the lower that students scored on an exam, the greater the gap between how they thought they had done and how they actually had done (Dunning et al., 2003).

The Triarchic Theory Having a good working memory and strong metacognitive skills, however, does not explain why some smart people keep making the same dumb choices in their relationships, or why people who don't seem especially bright are wildly successful in their jobs. That is why some psychological scientists reject the idea of a g factor as an adequate description of intelligence, and prefer to speak of different kinds of intelligence. To learn more about these differing perspectives, watch the video Theories of Intelligence 1.

Watch

Theories of Intelligence 1

One is Robert Sternberg (1988, 2004, 2012), who has developed the triarchic theory of intelligence (triarchic means “three-part”). He generally defines intelligence as “the skills and knowledge needed for success in life, according to one's own definition of success, within one's sociocultural context.” A guitar player, builder, scientist, and farmer can all be called successful if they make the most of their strengths, correct their weaknesses, and adapt to, select, and shape their environments to improve their lives. According to Sternberg, successfully intelligent people balance three kinds of intelligence: analytic, creative, and practical. If they are weak in one, they learn to work around that weakness:

Componential or analytical intelligence refers to the information-processing strategies you draw on when you are thinking intelligently about a problem: recognizing and defining the problem, comparing and contrasting, selecting a strategy for solving it, mastering and carrying out the strategy, and evaluating the result. Such abilities are required in every culture but are applied to different kinds of problems. One culture may emphasize the use of these components to solve abstract problems, whereas another may emphasize using the same components to maintain smooth relationships. In Western cultures, analytic intelligence is the kind that is most often measured on standardized tests and is associated with academic work.

Experiential or creative intelligence refers to your creativity in transferring skills to new situations. People with experiential intelligence cope well with novelty and learn quickly to make new tasks automatic. Those who are lacking in this area perform well only under a narrow set of circumstances. A student may do well in school, where assignments have specific due dates and feedback is immediate, but be less successful after graduation if her job requires her to set her own deadlines and her employer doesn't tell her how she is doing.

Contextual or practical intelligence refers to the practical application of intelligence, which requires you to take into account the different contexts in which you find yourself. If you are strong in contextual intelligence, you know when to adapt to the environment (you are in a dangerous neighborhood, so you become more vigilant). You know when to change environments (you had planned to be a teacher but discover that you dislike working with kids, so you switch to accounting). And you know when to fix the situation (your marriage is rocky, so you and your spouse go for counseling).

The Triarchic Theory of Intelligence

Contextual intelligence allows you to acquire tacit knowledge—practical, action-oriented strategies for achieving your goals that usually are not formally taught or even verbalized but must instead be inferred by observing others. College professors, business managers, and salespeople who have tacit knowledge and practical intelligence tend to be better than others at their jobs. Among college students, tacit knowledge about how to be a good student actually predicts academic success as well as entrance exams do (Sternberg et al., 2000).

Multiple Intelligences Howard Gardner has also argued for an expanded definition of intelligence. His multiple intelligences theory (Gardner, 1983, 2011) holds that an intelligence is best characterized as a capacity to process certain kinds of information. Just as bees, birds, and bears rely on the interplay of different biological and environmental mechanisms to navigate their cognitive worlds, so too do humans. Rather than spotlighting a single g factor, Gardner claims that the information-processing skills we possess can take many forms. A person with a great deal of musical intelligence, for example, might process information about pitch or rhythm more effectively than someone else, just as someone with a lot of interpersonal intelligence might be skilled at decoding the nonverbal behavior of others. This approach to defining intelligence is discussed in more detail in the video Theories of Intelligence 2.

Watch

Theories of Intelligence 2

Emotional Intelligence Other psychologists, too, are expanding the definition of intelligence. One of the most important kinds of nonintellectual “smarts” may be emotional intelligence, the ability to identify your own and other people's emotions accurately, express your emotions clearly, and manage emotions in yourself and others (Mayer & Salovey, 1997; Salovey & Grewal, 2005). People with high emotional intelligence, popularly known as “EQ,” use their emotions to motivate themselves, to spur creative thinking, and to deal empathically with others. People who are lacking in emotional intelligence are often unable to identify their own emotions; they may insist that they are not depressed when a relationship ends, but meanwhile they start drinking too much, become extremely irritable, and stop going out with friends. They may express emotions inappropriately, perhaps by acting violently or impulsively when they are angry or worried. They often misread nonverbal signals from others; they will give a long-winded account of all their problems even when the listener is obviously bored.

Studies of adults with brain damage suggest a biological basis for emotional intelligence. Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio (2003) has studied patients with prefrontal-lobe damage that makes them incapable of experiencing strong feelings. Although they score in the normal range on conventional mental tests, these patients persistently make “dumb,” irrational decisions because they cannot assign values to different options based on their own emotional reactions and cannot read emotional cues from others. Feeling and thinking are not always incompatible, as many people assume; in fact, one often requires the other.

Not everyone is enthusiastic about the proliferation of “intelligences” and their components. For example, some argue that emotional intelligence is not a special cognitive ability but a collection of ordinary personality traits, such as empathy and extroversion (Matthews, Zeidner, & Roberts, 2003, 2012). Nonetheless, broadening the notion of intelligence has been useful for several reasons. It has forced us to think more critically about what we mean by intelligence and to consider how different abilities help us function in our everyday lives. It has generated research on tests that provide ongoing feedback to the test taker so that the person can learn from the experience and improve his or her performance (Sternberg, 2004).

The cognitive approach has also led to a focus on teaching children strategies for improving their abilities in reading, writing, doing homework, and taking tests. Children have been taught to manage their time so they don't procrastinate and to study differently for multiple-choice exams than for essay exams (Sternberg et al., 1995). Most important, new approaches to intelligence encourage us to overcome the mental set of assuming that the only kind of abilities necessary for a successful life are the kind captured by IQ tests.

Theorists who argue for an expanded definition of intelligence would say that Taylor Swift has musical intelligence, a surveyor has spatial intelligence, and a compassionate friend has emotional intelligence. Should the definition be broadened in this way? Or are these abilities better defined as talents?

Motivation, Hard Work, and Intellectual Success

Even with a high IQ, emotional intelligence, and practical know-how, you still might get nowhere at all. Talent, unlike cream, does not inevitably rise to the top; success also depends on drive and determination.

Consider a finding from one of the longest-running psychological studies ever conducted. In 1921, Louis Terman and his associates began following more than 1,500 children with IQ scores in the top 1 percent of the distribution. These boys and girls, nicknamed Termites after Terman, started out bright, physically healthy, sociable, and well adjusted. As they entered adulthood, most became successful in the traditional ways of the times: Men went into careers and women became homemakers (Sears & Barbee, 1977; Terman & Oden, 1959). However, some gifted men failed to live up to their early promise, dropping out of school or drifting into low-level work. The 100 most successful men had been ambitious, were socially active, had many interests, and had been encouraged by their parents. The 100 least successful drifted casually through life. There was no average difference in IQ between the two groups.

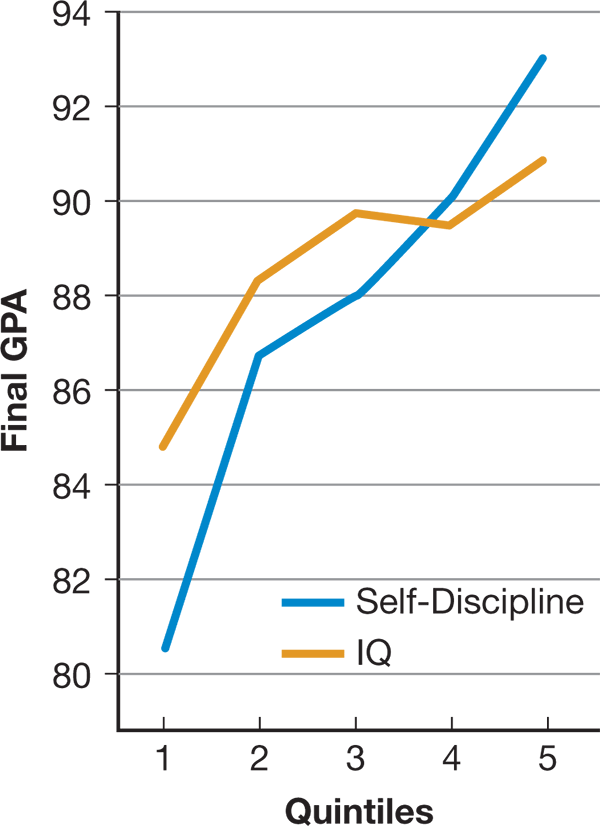

After you are motivated to succeed intellectually, you need self-discipline to reach your goals. In a longitudinal study of ethnically diverse eighth graders attending a magnet school, students received a self-discipline score based on their self-reports, parents' reports, teachers' reports, and questionnaires (Duckworth & Seligman, 2005). Students were also scored on a behavioral measure of self-discipline—their ability to delay gratification. (The teens had to choose between keeping an envelope containing a dollar or returning it in exchange for getting two dollars a week later.) Self-discipline accounted for more than twice as much of the variance in the students' final grades and achievement-test scores as IQ did. As you can see in Figure9.12, correlations between self-discipline and academic performance were much stronger than those between IQ and academic performance.

Figure 9.12

Grades, IQ, and Self-Discipline

Eighth-grade students were divided into five groups (quintiles) based on their IQ scores and then followed them for a year to test their academic achievement. Self-discipline was a stronger predictor of success than IQ was (Duckworth & Seligman, 2005).

Self-discipline and motivation to work hard at intellectual tasks depend, in turn, on your attitudes about intelligence and achievement, which are strongly influenced by cultural values. For many years, Harold Stevenson and his colleagues studied attitudes toward achievement in Asia and the United States, comparing large samples of elementary school-age children, parents, and teachers in Minneapolis, Chicago, Sendai (Japan), Taipei (Taiwan), and Beijing (Stevenson, Chen, & Lee, 1993; Stevenson & Stigler, 1992). Their results have much to teach us about the cultivation of intellect.

In 1980, the Asian children far outperformed the American children on a broad battery of mathematical and reading tests. On computations and word problems, there was virtually no overlap between schools, with the lowest-scoring Beijing schools doing better than the highest-scoring Chicago schools. (A similar gap occurred in reading scores.) By 1990, the gulf between the Asian and American children had grown even greater. Only 4 percent of the Chinese children and 10 percent of the Japanese children had math scores as low as those of the average American child. These differences could not be accounted for by educational resources: The Chinese had worse facilities and larger classes than the Americans, and on average, the Chinese parents were poorer and less educated than the American parents. Nor did it have anything to do with intellectual abilities in general; the American children were just as knowledgeable and capable as the Asian children on tests of general information.

But the Asians and Americans were worlds apart in several key ways:

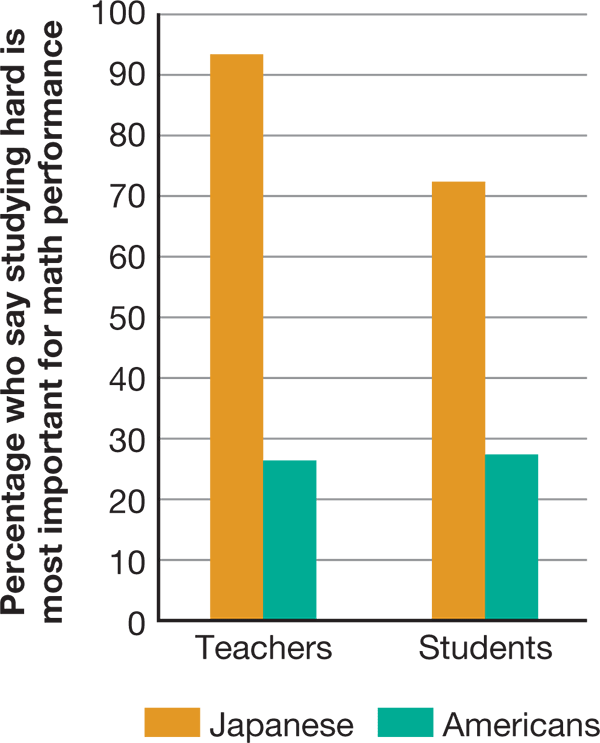

Beliefs about intelligence. American parents, teachers, and children were far more likely than Asians to believe that mathematical ability is innate (see Figure9.13). They tended to think that if you have this ability, you don't have to work hard, and if you don't have it, there's no point in trying.

Figure 9.13

What’s the Secret of Math Success?

Japanese schoolteachers and students are much more likely than their American counterparts to believe that the secret to doing well in math is working hard. Americans tend to think that you either have mathematical intelligence or you don’t (Stevenson, Chen, & Lee, 1993).

Standards. American parents had far lower standards for their children's performance; they were satisfied with scores barely above average on a 100-point test. In contrast, Chinese and Japanese parents were happy only with very high scores.

Values. American students did not value education as much as Asian students did, and they were more complacent about mediocre work. When asked what they would wish for if a wizard could give them anything they wanted, more than 60 percent of the Chinese fifth graders named something related to their education. Can you guess what the American children wanted? A majority said money or possessions.

When it comes to intellect, then, it's not just what you've got that counts, but what you do with it. Complacency, fatalism, low standards, and a desire for immediate gratification can prevent people from recognizing what they don't know and reduce their efforts to learn.