10.1

Reconstructing the Past

What would life be like if you could never form any new memories? That's what happens to older people who are suffering from dementia, and it also sometimes happens to younger people who have brain injuries or diseases. Henry Molaison's case is the most intensely studied in the annals of medicine (Corkin, 1984, 2013; Corkin et al., 1997; Hilts, 1995; Milner, 1970; Ogden & Corkin, 1991). In 1953, when Henry, known in the scientific literature as H. M., was 27 years old, surgeons made a last-ditch effort to cure his unrelenting, uncontrollable epileptic seizures by removing his hippocampus, most of his amygdala, and a portion of his temporal lobes. The operation did achieve its goal: Henry's seizures became milder and could be controlled by medication. But his memory had been affected profoundly: He could no longer remember new experiences for much longer than 15 minutes. Facts, songs, stories, and faces all vanished like water down a drain. He would read the same magazine over and over without realizing it; he could not recall the day of the week, the year, or even his most recent meal.

Henry still loved to do crossword puzzles and play bingo, skills he had learned long before the operation. And he remained cheerful, even though he knew he had memory problems. He would occasionally recall an unusually emotional event, such as the assassination of someone named Kennedy, and he sometimes remembered that both of his parents were dead. But according to Suzanne Corkin, who studied H. M. extensively, these “islands of remembering” were the exceptions in a vast sea of forgetfulness. This good-natured man felt sad that he could never make friends because he could never remember anyone, not even the scientists who studied him for decades. He always thought he was much younger than he really was, and he was unable to recognize a photograph of his own face; he was stuck in a time warp from the past.

After he died in 2008 at age 82, one neuroscientist said that H. M. gave science the ultimate gift: his memory (Ogden, 2012). He also taught neuroscientists a great deal about the biology of memory; before his surgery, scientists did not realize the important role played by the hippocampus. We will meet H. M. again at several points in this chapter, and you can learn more about his remarkable case in the video When Memory Fails. For now, let's consider the fragility of memory; how it's constructed, how it's susceptible to distortion, and how it might be manipulated.

Watch

When Memory Fails

The Manufacture of Memory

People's descriptions of memory have always been influenced by the technology of their time. Ancient philosophers compared memory to a soft wax tablet that would preserve anything imprinted on it. Later, with the advent of the printing press, people began to describe memory as a gigantic library, storing specific events and facts for later retrieval. Today, many people compare memory to a digital recorder or video camera, automatically capturing every moment of their lives.

Popular and appealing though this belief about memory is, it is wrong. Unless you are someone like Brad Williams or Jill Price, who have extraordinary memory abilities, not everything that happens to you or impinges on your senses is tucked away for later use. Memory is selective. If it were not, our minds would be cluttered with mental junk: the temperature at noon on Thursday, the price of milk two years ago, a phone number needed only once. Moreover, remembering is not at all like replaying a recording of an event. It is more like watching a few unconnected clips and then figuring out what the rest of the recording must have been like.

One of the first scientists to make this point was British psychologist Sir Frederic Bartlett (1932). Bartlett asked people to read lengthy, unfamiliar stories from other cultures and then tell the stories back to him. As the volunteers tried to recall the stories, they made interesting errors: They often eliminated or changed details that did not make sense to them, and they added other details from their own culture—details that made the story more sensible to them. Memory, Bartlett concluded, must therefore be largely a reconstructive process. We may reproduce some kinds of simple information by rote, said Bartlett, but when we remember complex information, our memories are distorted by previous knowledge and beliefs. Since Bartlett's time, hundreds of studies have supported his original idea, showing that it applies to all sorts of memories.

In reconstructing their memories, people often draw on many sources. Suppose that someone asks you to describe one of your early birthday parties. You may have some direct memory of the event, but you may also incorporate information from family stories, photographs, or home videos, and even from accounts of other people's birthdays and reenactments of birthdays on television. You take all these bits and pieces and build one integrated account. Later, you may not be able to distinguish your actual memory from information you got elsewhere—a phenomenon known as source misattribution, or sometimes source confusion (Johnson, Hashtroudi, & Lindsay, 1993; Mitchell & Johnson, 2009).

If these happy children remember this birthday party later in life, their constructions may include information picked up from family photographs, videos, and stories. And they will probably be unable to distinguish their actual memories from information they got elsewhere.

A dramatic instance of reconstruction once occurred with H. M. (Ogden & Corkin, 1991). After eating a chocolate Valentine's Day heart, H. M. stuck the shiny red wrapping in his shirt pocket. Two hours later, while searching for his handkerchief, he pulled out the paper and looked at it in puzzlement. When a researcher asked why he had the paper in his pocket, he replied, “Well, it could have been wrapped around a big chocolate heart. It must be Valentine's Day!” But a short time later, when she asked him to take out the paper again and say why he had it in his pocket, he replied, “Well, it might have been wrapped around a big chocolate rabbit. It must be Easter!” Sadly, H. M. had to reconstruct the past; his damaged brain could not recall it in any other way. But those of us with normal memory abilities also reconstruct, far more often than we realize.

Of course, some shocking or tragic events—such as earthquakes, a mass killing, an assassination—do hold a special place in memory. So do some unusual, exhilaratingly happy events, such as learning that you just won a lottery. Years ago, these vivid recollections of emotional and important events were labeled flashbulb memories, to capture the surprise, illumination, and seemingly photographic detail that characterize them (Brown & Kulik, 1977). Some flashbulb memories can last for years. In a Danish study, older people who had lived through the Nazi occupation of their country in World War II retained accurate memories, for decades, of the day that the radio announced liberation (Berntsen & Thomsen, 2005). Sometimes, events that are unsurprising can also produce memories with the characteristics of flashbulbs—vivid, emotion-laden images—if they have significant personal or national consequences, such as a student's first day of college or an extraordinary national event (Talarico, 2009; Tinti et al., 2009).

Yet even flashbulb memories are not always complete or accurate. People typically remember the gist of a startling, emotional event they experienced or witnessed, but when researchers question them about their memories over time, errors creep into the details, and after a few years, some people even forget the gist (Neisser & Harsch, 1992; Talarico & Rubin, 2003). Just one day after the 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, researchers asked college students when they had first heard the news of the attacks, who had told them the news, and what they had been doing at the time. They also asked the students to report details about a mundane event from the days immediately before the attacks, to allow a comparison of ordinary memories with flashbulb ones. The students were retested at various intervals, up to eight months later. Over time, the vividness of the flashbulb memories and the students' confidence in these memories remained higher than for the everyday memories. Their confidence, however, was misplaced. The details the students reported became less and less consistent (and equally inconsistent) for both types of memories (Hirst et al., 2015; Talarico & Rubin, 2003).

Even with flashbulb memories, then, facts tend to get mixed with fiction. Remembering is an active process, one that involves not only dredging up stored information but also putting two and two together to reconstruct the past. Sometimes, unfortunately, we put two and two together and get five.

What Do You Remember?

The Conditions of Confabulation

Because memory is reconstructive, it is subject to confabulation—confusing an event that happened to someone else with one that happened to you, or coming to believe that you remember something that never really happened. Such confabulations are especially likely under certain circumstances (Garry et al., 1996; Hyman & Pentland, 1996; Mitchell & Johnson, 2009):

You have thought, heard, or told others about the imagined event many times. Suppose that at family gatherings you keep hearing about the time that your uncle Sam got so angry at a party that he began pounding the wall with a hammer, with such force that the wall collapsed. The story is so colorful that you can practically see it unfold in your mind. The more you think about this event, the more likely you are to believe that you actually were there and that it happened as you “remember” it, even if you were sound asleep in another house. This process has been called imagination inflation because your own active imagination inflates your belief that the event really occurred as you assume it did (Garry & Polaschek, 2000). Even merely explaining how a hypothetical childhood experience could have happened inflates people's confidence that it really did. Explaining an event makes it seem more familiar and thus real (Sharman, Manning, & Garry, 2005).

Brian Williams is a familiar face to many U.S. television viewers. As the main news anchor at NBC since 2004, his nightly accounts of the day's events provided viewers with timely, reliable information. In 2015, however, he was suspended over an incident in which he misrepresented his involvement in a helicopter incident during the Iraq War in 2003. Was this a case of lying, embellishment, confabulation, or suggestion, or was it simply an example of faulty memory?

The image of the event contains lots of details that make it feel real. Ordinarily, we can distinguish imagined events from real ones by the amount of detail we recall; memories of real events tend to contain more details. But the longer you think about an imagined event, the more likely you are to embroider those images with details—what your uncle was wearing, the crumbling plaster, the sound of the hammer—and these added details will persuade you that you really do remember the event and aren't just confusing other people's reports with your own experience (Johnson et al., 2011).

The event is easy to imagine. If imagining an event takes little effort (as does visualizing a man pounding a wall with a hammer), then we are especially likely to think that a memory is real rather than false. In contrast, when we must make an effort to form an image of an experience, a place we have never seen, or an activity that is utterly foreign to us, we use our cognitive effort as a cue that we are merely imagining the event or have heard about it from others.

As a result of confabulation, you may end up with a memory that feels emotionally, vividly real to you and yet is false (Mitchell & Johnson, 2009). This means that your feelings about an event, no matter how strong they are, do not guarantee that the event really took place. Consider again our Sam story, which happens to be true. A woman we know believed for years that she had been present as an 11-year-old child when her uncle destroyed the wall. Because the story was so vivid and upsetting to her, she felt angry at him for what she thought was his mean and violent behavior, and she assumed that she must have been angry at the time as well. Then, as an adult, she learned that she was not at the party at all but had merely heard about it repeatedly over the years. Moreover, Sam had not pounded the wall in anger, but as a joke, to inform the assembled guests that he and his wife were about to remodel their home. Nevertheless, our friend's family has had a hard time convincing her that her “memory” of this event is entirely wrong, and they are not sure she believes them yet.

As the Sam story illustrates, and as laboratory research verifies, false memories can be as stable over time as true ones (Johnson, Mitchell, & Ankudowich, 2012). There's just no getting around it: Memory is reconstructive.

The Eyewitness on Trial

As we've seen, the reconstructive nature of memory helps the mind work efficiently. Instead of cramming our brains with infinite details, we can store the essentials of an experience and then use our knowledge of the world to figure out the specifics when we need them. But precisely because memory is so often reconstructive, it is also vulnerable to suggestion—to ideas implanted in our minds after the event, which then become associated with it. This fact raises thorny problems in legal cases that involve eyewitness testimony or people's memories of what happened, when, and to whom.

Take, for example, the case of Jennifer Thompson and Ronald Cotton. After being raped, Thompson identified who she believed was her assailant from a book of mug shots, and later she identified the same man in a lineup. After a jury heard her eyewitness testimony, Cotton was convicted and sentenced to prison for two life terms. A few years later, evidence surfaced that the real rapist might have been another man, a convict named Bobby Poole. A judge ordered a new trial, where Jennifer Thompson looked at both men face to face and once again said that Ronald Cotton was the man who raped her. Cotton was sent back to prison. Eleven years later, DNA evidence completely exonerated Cotton and just as unequivocally implicated Poole, who confessed to the crime. As Thompson learned to her sorrow, eyewitness testimony is not always reliable. Lineups and photo arrays don't necessarily help because witnesses may simply identify the person who looks most like the perpetrator of the crime (Fitzgerald, Oriet, & Price, 2015; Wells & Olson, 2003). As a result, some convictions based on eyewitness testimony, like that of Ronald Cotton, turn out to be tragic mistakes.

Ronald Cotton (left) was convicted of rape solely on the basis of eyewitness testimony by Jennifer Thompson (right). He spent 11 years in prison until DNA evidence established that he could not have committed the crime and that the real rapist was another man. Cotton and Thompson became friends after his release. In thinking about cases in which an eyewitness provides the only evidence against a suspect, a critical thinker would ask: How accurate is eyewitness testimony, even when the witness is the victim? How trustworthy are our memories, even of traumatic events? Psychological scientists have learned some startling answers, as this chapter will show.

Eyewitnesses are especially likely to make mistaken identifications when the suspect's ethnicity differs from their own. Because of unfamiliarity with other ethnic groups, the eyewitness may focus solely on the ethnicity of the person they see committing a crime (“He's black”; “She's white”; “He's an Arab”) and ignore the distinctive features that would later make identification more accurate (Knuycky, Kleider, & Cavrak, 2014; Wilson, Hugenberg, & Bernstein, 2013).

In a program of research spanning more than four decades, Elizabeth Loftus and her colleagues have shown that memories are also influenced by the way in which questions are put to the eyewitness and by suggestive comments made during an interrogation or interview. In one classic study, the researchers showed how even subtle changes in the wording of questions can lead a witness to give different answers. Participants first watched short films depicting car collisions. Afterward, the researchers asked some of them, “About how fast were the cars going when they hit each other?” Other viewers were asked the same question, but with the verb changed to smashed, collided, bumped, or contacted. Estimates of how fast the cars were going varied, depending on which word was used. Smashed produced the highest average speed estimates (40.8 mph), followed by collided (39.3 mph), bumped (38.1 mph), hit (34.0 mph), and contacted (31.8 mph) (Loftus & Palmer, 1974).

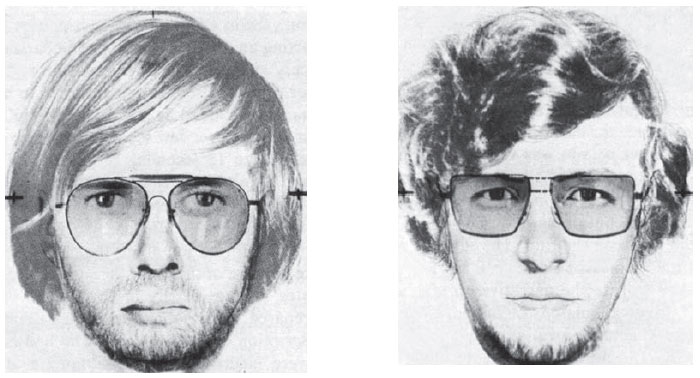

Misleading information from other sources also can profoundly alter what witnesses report. Consider what happened when students were shown the face of a young man who had straight hair, then heard a description of the face supposedly written by another witness—a description that wrongly said the man had light, curly hair (see Figure10.1). When the students reconstructed the face using a kit of facial features, a third of their reconstructions contained the misleading detail, whereas only 5 percent contained it when curly hair was not mentioned (Loftus & Greene, 1980). In real life, misleading information about a perpetrator's appearance can reduce an eyewitness's ability to identify the real perpetrator later in a lineup (Zajac & Henderson, 2009).

Figure 10.1

The Influence of Misleading Information

Students saw the face of a young man with straight hair and then had to reconstruct it from memory. On the left is one student's reconstruction in the absence of misleading information about the man’s hair. On the right is another person’s reconstruction of the same face after exposure to misleading information that mentioned curly hair (Loftus & Greene, 1980).

Does the number of eyewitnesses affect a person's susceptibility to misleading information? In a study of this question, people first watched a video of a simulated crime and later read three eyewitness reports about the crime, each report containing the same misleading claim—such as about the location of objects, the thief's actions, or the name on the side of the suspect van. One group was told that a single person wrote all three reports, whereas another group was told that each report was written by a different person. It made no difference; a single witness's report proved to be as influential as the reports of three different witnesses. Such is the power of a single witness's voice (Foster et al., 2012).

Leading questions, suggestive comments, and misleading information affect people's memories not only for events they have witnessed but also for their own experiences. Researchers have successfully used these techniques to induce people to believe they are recalling complicated events from early in life that never actually happened, such as getting lost in a shopping mall, being hospitalized for a high fever, being harassed by a bully, getting in trouble for playing a prank on a first-grade teacher, or spilling punch all over the mother of the bride at a wedding (Hyman & Pentland, 1996; Lindsay et al., 2004; Loftus & Pickrell, 1995; Mazzoni et al., 1999). When people were shown a phony Disneyland ad featuring Bugs Bunny, about 16 percent later recalled having met a Bugs character at Disneyland (Braun, Ellis, & Loftus, 2002). In later studies, the percentages were even higher. Some people even claimed to remember shaking hands with the character, hugging him, or seeing him in a parade. But these memories were impossible, because Bugs Bunny is a Warner Bros. creation and would definitely be rabbit non grata at Disneyland!

Children's Testimony

The power of suggestion can affect anyone, but its impact on children who are being questioned about possible sexual or physical abuse is especially worrisome. How can adults determine whether a young child has been sexually molested without influencing what the child says? The answer is crucial. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, accusations of child abuse in daycare centers skyrocketed. After being interviewed by therapists and police investigators, children were claiming that their teachers had molested them in the most terrible ways: hanging them in trees, raping them, and even forcing them to eat feces. Although in no case had parents actually seen the daycare teachers treating the children badly, although none of the children had complained to their parents, and although none of the parents had noticed any symptoms or problems in their children, the accused teachers were often sentenced to many years in prison.

Thanks largely to research by psychological scientists, the hysteria eventually subsided and people were able to assess more clearly what had gone wrong in the way children had been interviewed in these cases. Today, we know that although children, like adults, can remember many things accurately, they can also be influenced by an interviewer's leading questions, suggestions, or pressure to report certain information (Ceci & Bruck, 1995). Moreover, in the courtroom, the style of questions put to children under cross-examination often leads them to be highly inaccurate (O'Neill & Zajac, 2012). The question to ask, therefore, is not “Can children's memories be trusted?” but “Under what conditions are children apt to be suggestible, and to report that something happened to them when in fact it did not?”

Children's testimony is often crucial in child sexual abuse cases. Under what conditions do children make reliable or unreliable witnesses?

The answer, from many experimental studies, is that a child is more likely to give a false report when an interviewer strongly believes that the child has been molested and then uses suggestive techniques to get the child to reveal molestation (Bruck, 2003). Interviewers who are biased in this way seek only confirming evidence and ignore discrepant evidence and other explanations for a child's behavior. They reject a child's denial of having been molested and assume the child is “in denial.” They use techniques that encourage imagination inflation (“Let's pretend it happened”) and that blur reality and fantasy in the child's mind. They pressure or encourage the child to describe terrible events, badger the child with repeated questions, tell the child that “everyone else” said the events happened, or use bribes and threats (Poole & Lamb, 1998).

A team of researchers analyzed the actual transcripts of interrogations of children in the first highly publicized sexual abuse case in the United States, the McMartin preschool case (which ended in a hung jury). Then they applied the same suggestive techniques in an experiment with preschool children (Garven et al., 1998). A young man visited children at their preschool, read them a story, and handed out treats. The man did nothing aggressive, inappropriate, or surprising. A week later, an experimenter questioned the children individually about the man's visit. She asked children in one group leading questions (“Did he bump the teacher? Did he throw a crayon at a kid who was talking?” “Did he tell you a secret and tell you not to tell?”). She asked a second group the same questions but also applied influence techniques used by interrogators in the McMartin and other daycare cases: telling the children what “other kids” had supposedly said, expressing disappointment if answers were negative, and praising the children for making allegations.

In the first group, children said “Yes, it happened” to about 17 percent of the false allegations about the man's visit. And in the second group, they said “yes” to the false allegations suggested to them a whopping 58 percent of the time. As you can see in Figure10.2, the 3-year-olds in this group, on average, said “yes” to over 80 percent of the false allegations, and the 4- to 6-year-olds said “yes” to over half of the allegations. Note that the interviews in this study lasted only 5 to 10 minutes, whereas in actual investigations, interviewers often question children repeatedly over many weeks or months.

Figure10.2

Social Pressure and False Allegations

[[For Revel: Insert Interactive 10.2]]

Many people believe that children cannot be induced to make up experiences that are truly traumatic, but psychologists have shown that this assumption, too, is wrong. When schoolchildren were asked for their recollections of an actual sniper incident at their school, many of those who had been absent from school that day reported memories of hearing shots, seeing someone lying on the ground, and other details they could not possibly have experienced directly. Apparently, they had been influenced by the accounts of the children who had been there (Pynoos & Nader, 1989). Indeed, rumor and hearsay play a big role in promoting false beliefs and memories in children, just as they do in adults (Principe et al., 2006).

As a result of such findings, psychologists have been able to develop ways of interviewing children that reduce the chances of false reporting. If the interviewer says, “Tell me the reason you came to talk to me today,” and nothing more, most actual victims will disclose what happened to them (Bruck, 2003). The interviewer must not assume that the child was molested, must avoid leading or suggestive questions, and must understand that children do not speak the way adults do. Young children often drift from topic to topic, and their words may not be the words adults would use (Poole & Lamb, 1998). One little girl being interviewed thought her “private parts” were her elbows!

In sum, children, like adults, can be accurate in what they report and, also like adults, they can distort, forget, fantasize, and be misled. As research shows, their memory processes are only human.