11.3

The Nature of Stress

As we have seen, emotions can take many forms, varying in complexity and intensity, depending on physiology, cognitive processes, and cultural rules. These same three factors can help us understand those difficult situations in which negative emotions become chronically stressful, and in which chronic stress can create negative emotions.

When people say they are “under stress,” they mean all sorts of things: They are having recurring conflicts with a parent, are feeling frustrated and angry about their lives, are fighting with a partner, are overwhelmed with caring for a sick child, can't keep up with work obligations, or just lost a job. Are these stressors linked to illness—to migraines, stomachaches, flu, or more life-threatening diseases such as cancer? And do they affect everyone in the same way?

Will This Survey Stress You Out?

Stress and the Body

The modern era of stress research began in 1956, when physician Hans Selye published The Stress of Life. Environmental stressors such as heat, cold, toxins, and danger, Selye wrote, disrupt the body's equilibrium. The body then mobilizes its resources to fight off these stressors and restore normal functioning, as shown in the video Fight or Flight. Selye described the body's response to stressors of all kinds as a general adaptation syndrome, a set of physiological reactions that occur in three phases:

Watch

Fight or Flight

The alarm phase, in which the body mobilizes the sympathetic nervous system to meet the immediate threat. The threat could be anything from taking a test you haven't studied for to running from a rabid dog. As we saw earlier, the release of adrenal hormones, epinephrine and norepinephrine, occurs with any intense emotion. It boosts energy, tenses muscles, reduces sensitivity to pain, shuts down digestion (so that blood will flow more efficiently to the brain, muscles, and skin), and increases blood pressure. Decades before Selye, psychologist Walter Cannon (1929) described these changes as the “fight-or-flight” response, a phrase still in use.

The Body's Reactions to Stress

The resistance phase, in which your body attempts to resist or cope with a stressor that cannot be avoided. During this phase, the physiological responses of the alarm phase continue, but these very responses make the body more vulnerable to other stressors. When your body has mobilized to deal with a heat wave or pain from a broken leg, you may find you are more easily annoyed by minor frustrations. In most cases, the body will eventually adapt to the stressor and return to normal.

The exhaustion phase, in which persistent stress depletes the body of energy, thereby increasing vulnerability to physical problems and illness. The same reactions that allow the body to respond effectively in the alarm and resistance phases are unhealthy as long-range responses. Tense muscles can cause headache and neck pain. Increased blood pressure can become chronic hypertension. If normal digestive processes are interrupted or shut down for too long, digestive disorders may result.

Selye did not believe that people should aim for a stress-free life. Some stress, he said, is positive and productive, even if it also requires the body to produce short-term energy: competing in an athletic event, falling in love, working hard on a project you enjoy. And some negative stress is simply unavoidable; it's called life. To get an idea of what your body goes through during stress, watch the video Stress and Your Health 1.

Watch

Stress and Your Health 2

Current Approaches One of Selye's most important observations was that the very biological changes that are adaptive in the short run, because they permit the body to respond quickly to danger, can become hazardous in the long run (McEwen, 2007). Modern researchers are learning how this happens.

When you are under stress, your brain's hypothalamus sends messages to the endocrine glands along two major pathways. One, as Selye observed, activates the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system for “fight or flight,” producing the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine from the inner part (medulla) of the adrenal glands. In addition, the hypothalamus initiates activity along the HPA axis (HPA stands for hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal cortex). The hypothalamus releases chemical messengers that communicate with the pituitary gland, which in turn sends messages to the outer part (cortex) of the adrenal glands. The adrenal cortex secretes cortisol and other hormones that elevate blood sugar and protect the body's tissues from inflammation in case of injury (see Figure11.3).

Figure 11.3

The Brain and Body Under Stress

One result of HPA axis activation is increased energy, which is crucial for short-term responses to stress (Kemeny, 2003). But if cortisol and other stress hormones stay high too long, they can lead to hypertension, immune disorders, other physical ailments, and emotional problems such as depression (Ping et al., 2015). Elevated levels of cortisol also motivate animals (and presumably humans, too) to seek out rich comfort foods and store the extra calories as abdominal fat.

The cumulative effects of external sources of stress may help us to understand why people at the lower rungs of the socioeconomic ladder have worse health and higher mortality rates for almost every disease and medical condition than do those at the top (Adler & Snibbe, 2003). In addition to the obvious reasons of lack of access to good medical care and reliance on diets that lead to obesity and type 2 diabetes, low-income people often live with continuous environmental stressors: higher crime rates, discrimination, rundown housing, and greater exposure to hazards such as chemical contamination (Gallo & Matthews, 2003). These conditions affect urban blacks disproportionately and may help account for their higher incidence of hypertension (high blood pressure), which can lead to kidney disease, strokes, and heart attacks (Clark et al., 1999; Pascoe & Richman, 2009).

Children are particularly vulnerable to the stressors associated with poverty or maltreatment by parents: The more years they are exposed to family disruption, violence, and instability, the higher their cortisol levels and the greater the snowballing negative effect on their physical health, mental health, and cognitive abilities (especially working memory, the ability to hold items of information in memory for current use) in adolescence and adulthood. Persistent childhood stress takes its toll on health both through biological mechanisms, such as chronically elevated cortisol, and behavioral ones. Children living with chronic stress often become hypervigilant to danger, mistrust others, have poor relationships, are unable to regulate their emotions, abuse drugs, and don't eat healthy food. No wonder that by the time they are adults, they have an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disorders, type 2 diabetes, and early mortality (Evans & Schamberg, 2009; Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011).

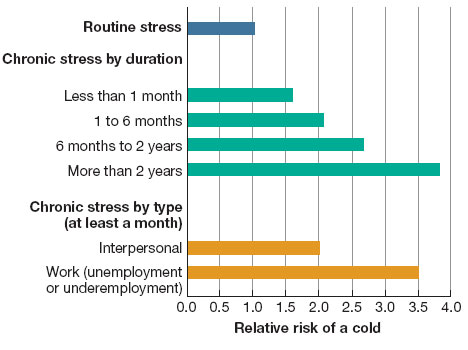

Because work is central in most people's lives, the effects of persistent unemployment can threaten health for people at all income levels, even increasing their vulnerability to the common cold. In one study, heroic volunteers were given either ordinary nose drops or nose drops containing a cold virus, and then were quarantined for 5 days. The people most likely to get a cold's miserable symptoms were those who had been underemployed or unemployed for at least a month. As Figure11.4 shows, the longer the work problems lasted, the greater the likelihood of illness (Cohen et al., 1998).

Figure 11.4

Stress and the Common Cold

Chronic stress lasting a month or more boosts the risk of catching a cold. The risk is increased among people undergoing problems with their friends or loved ones; it is highest among people who are out of work (Cohen et al., 1998).

Nonetheless, the physiological changes caused by stress do not occur to the same extent in everyone. People's responses to stress vary according to their learning history, gender, preexisting medical conditions, and genetic predisposition for high blood pressure, heart disease, obesity, diabetes, or other health problems (Belsky & Pluess, 2013; McEwen, 2000, 2007). This is why some people respond to the same stressor with much greater increases in blood pressure, heart rate, and hormone levels than other individuals do, and their physical changes take longer to return to normal. These hyperresponsive individuals may be the ones most at risk for eventual illness. For some tips on how to lessen the impact of stress in your life, watch the video Stress and Your Health 2.

Watch

Stress and Your Health 1

The Immune System: PNI Researchers in the field of health psychology (and its medical relative, behavioral medicine) investigate all aspects of how mind and body affect each other to preserve wellness or cause illness. To investigate these interweaving factors, researchers have created an interdisciplinary specialty with the cumbersome name psychoneuroimmunology, or PNI for short. The “psycho” part stands for psychological processes such as emotions and perceptions; “neuro” for the nervous and endocrine systems; and “immunology” for the immune system, which enables the body to fight disease and infection.

The immune system consists of fighter cells that look more fantastical than any alien creature Hollywood could design. This one is about to engulf and destroy a cigarette-shaped parasite that causes a tropical disease.

PNI researchers are especially interested in the white blood cells of the immune system, which are designed to recognize foreign or harmful substances (antigens), such as flu viruses, bacteria, and tumor cells, and then destroy or deactivate them. The immune system deploys different kinds of white blood cells as weapons, depending on the nature of the enemy. Natural killer cells are important in tumor detection and rejection, and are involved in protection against the spread of cancer cells and viruses. Helper T cells enhance and regulate the immune response; they are the primary target of the HIV virus that causes AIDS. Chemicals produced by the immune cells are sent to the brain, and the brain in turn sends chemical signals to stimulate or restrain the immune system. Anything that disrupts this communication loop—whether drugs, surgery, or chronic stress—can weaken or suppress the immune system (Segerstrom & Miller, 2004).

Some PNI researchers have gotten down to the level of cell damage to see how stress can lead to illness, aging, and even premature death. At the end of every chromosome is a protein complex called a telomere that, in essence, tells the cell how long it has to live. Every time a cell divides, enzymes whittle away a tiny piece of the telomere; when it is reduced to almost nothing, the cell stops dividing and dies. Chronic stress, especially if it begins in childhood, appears to shorten the telomeres (Puterman et al., 2015). One team of researchers compared two groups of healthy 20- to 50-year-old women: 19 who had healthy children and 39 who were primary caregivers of a child chronically ill with a serious disease, such as cerebral palsy. Of course, the mothers of the sick children felt that they were under stress, but they also had significantly greater cell damage than did the mothers of healthy children. In fact, the cells of the highly stressed women looked like those of women at least 10 years older, and their telomeres were much shorter (Epel et al., 2004). To learn more about how biological factors interact with other factors to influence health, watch the video Health Psychology.

Watch

Health Psychology

Stress and the Mind

Before you try to persuade your instructors that the stress of constant studying is bad for your health, consider this mystery: The large majority of individuals who are living with stressors, even serious ones such as loss of a job or the death of a loved one, do not get sick (Bonanno, 2004; Taylor, Repetti, & Seeman, 1997). What protects them? What attitudes and qualities are most strongly related to health, well-being, and long life?

Optimism When something bad happens to you, what is your first reaction? Do you tell yourself that you will somehow come through it okay, or do you gloomily mutter, “More proof that if something can go wrong for me, it will”? In a fundamental way, optimism—the general expectation that things will go well in spite of occasional setbacks—makes life possible. If people are in a jam but believe things will get better eventually, they will keep striving to make that prediction come true. Even despondent fans of the Chicago Cubs, who have not won the World Series in living memory, maintain a lunatic optimism that “there's always next year.”

At first, studies of optimism reported (optimistically!) that optimism is better for health, well-being, and even longevity than pessimism is (Carver & Scheier, 2002; Maruta et al., 2000). You can see why popularizers in the media ran far with this ball, some claiming that having an optimistic outlook would prolong the life of people suffering from serious illnesses. Unfortunately, that hope proved false: A team of Australian researchers who followed 179 patients with lung cancer over a period of 8 years found that optimism made no difference in who lived or in how long they lived (Schofield et al., 2004). Indeed, for every study showing the benefits of optimism, another shows that it can actually be harmful: Among other things, optimists are more likely to keep gambling, even when they lose money, and they can be more vulnerable to depression when the hoped-for outcome does not occur (McNulty & Fincham, 2012). Optimism also backfires when it keeps people from preparing themselves for complications of surgery (“Oh, everything will be fine”) or causes them to underestimate risks to their health (Friedman & Martin, 2011).

Pessimists naturally accuse optimists of being unrealistic, and often that is true! For optimism to reap its benefits, it must be grounded in reality, spurring people to take better care of themselves and to regard problems and bad news as difficulties they can overcome. Realistic optimists are more likely than pessimists to be active problem solvers, get support from friends, and seek information that can help them (Brissette, Scheier, & Carver, 2002; Geers, Wellman, & Lassiter, 2009). They keep their senses of humor, plan for the future, and reinterpret the situation in a positive light. Pessimists, in contrast, often do self-destructive things: They drink too much, smoke, fail to wear seat belts, drive too fast, and refuse to take medication for illness. So, however, do unrealistic optimists.

Is the glass half-empty or half-full? Optimists may be likely to see the benefits of this situation (“There’s something more than nothing!”), whereas pessimists may be likely to see the downside (“It’s not all that it could be”).

Conscientiousness and Control Thus, it is not optimism by itself that predicts health and well-being. You can recite “Everything is good! Everything will work out!” 20 times a day, but it won't get you much (except odd glances from your classmates). Optimism needs a behavioral partner.

In one of the longest longitudinal studies ever conducted in psychology—90 years!—researchers were able to follow the lives of more than 1,500 children originally studied by Lewis Terman, beginning in 1921 (see Chapter 9). Terman followed these children, affectionately called the “Termites,” long into their adulthood, and when he died in 1956, other researchers took up the project (Kern, Della Porta, & Friedman, 2014). Health psychologists Howard Friedman and Leslie Martin (2011) found that the secret to longevity for the Termites was conscientiousness, the ability to persist in pursuit of goals, get a good education, work hard but enjoy the work and its challenges, and be responsible. Conscientious people are optimists, in the sense that they believe their efforts will pay off, and they act in ways to make that expectation come true. The findings on the Termites, who were largely a homogeneous cohort that was white and middle class, have been replicated across more than 20 independent samples that differed in terms of ethnicity and social class (Deary, Weiss, & Batty, 2010).

Conscientiousness is related to another important cognitive ingredient in health: having an internal locus of control. Locus of control refers to your general expectation about whether you can control the things that happen to you (Rotter, 1990). People who have an internal locus of control (“internals”) tend to believe that they are responsible for what happens to them. Those who have an external locus of control (“externals”) tend to believe that their lives are controlled by luck, fate, or other people. Having an internal locus of control, especially concerning things you can do right now rather than vague future events, is associated with good health, academic achievement, political activism, and emotional well-being (Frazier et al., 2011; Roepke & Grant, 2011; Strickland, 1989).

Most people can tolerate all kinds of stressors if they feel able to predict or control them. Consider crowding. Mice get really nasty when they're crowded, but many people love crowds, voluntarily getting squashed in New York's Times Square on New Year's Eve or at a rock concert. Human beings show signs of stress not when they are actually crowded but when they feel crowded (Evans, Lepore, & Allen, 2000). People who have the greatest control over their work pace and activities, such as executives and managers, have fewer illnesses and stress symptoms than do employees who have little control, who feel trapped doing repetitive tasks, and who have a low chance of promotion (Karasek & Theorell, 1990). People can usually cope better with continuous, predictable noise (such as the hum of a bustling city street) than with intermittent, loud, unpredictable noise (such as the racket of airplanes heard by people living near airports). This information has proven important in medical care because the high-decibel beeps and alarms going off in hospital rooms, at unpredictable intervals, is often very stressful to patients, elevating their blood pressure and cortisol (Stewart, 2011; Szalma & Hancock, 2011).

Feeling in control affects the immune system, which may be why it helps to speed up recovery from surgery and some diseases (E. Skinner, 1996). People who have an internal locus of control are better able than externals to resist infection by cold viruses and even the health-impairing effects of poverty and discrimination (Cohen, Tyrrell, & Smith, 1993; Krieger & Sidney, 1996; Lachman & Weaver, 1998). As with realistic optimism, feeling in control also makes people more likely to take action to improve their health when necessary. In studies of patients recovering from heart attacks, those who believed the heart attack occurred because they smoked, didn't exercise, or had a stressful job were more likely to change their bad habits and recover quickly. In contrast, those who thought their illness was due to bad luck or fate—factors outside their control—were less likely to generate plans for recovery and more likely to resume their old unhealthy habits (Affleck et al., 1987; Ewart, 1995).

Overall, then, a sense of control is a good thing, but critical thinkers might want to ask: Control over what? It is surely not beneficial for people to believe they can control absolutely every aspect of their lives; some things, such as death, taxes, or being a random victim of a crime, are out of anyone's control. Health and well-being are not enhanced by self-blame (“Whatever goes wrong with my health is my fault”) or the belief that all disease can be prevented by doing the right thing (“If I take vitamins and hold the right positive attitude, I'll never get sick”).