12.3

The Erotic Animal: Motives for Sex

Most people believe that sex is a biological drive, merely a matter of doing what comes naturally. “What's there to discuss about sexual motivation?” they say. “Isn't it all inborn, inevitable, and inherently pleasurable?”

It is certainly true that in most other species, sexual behavior is genetically programmed. Without instruction, a male stickleback fish knows exactly what to do with a female stickleback, and a whooping crane knows when to whoop. But as sex researcher and therapist Leonore Tiefer (2004) has observed, for human beings “sex is not a natural act.” Sex, she says, is more like dancing than digestion, something you learn rather than a simple physiological process. For one thing, the activities that one culture considers “natural”—such as mouth-to-mouth kissing or oral sex—are often considered unnatural in another culture or historical time. Second, people have to learn from experience and culture what they are supposed to do with their sexual desires and how they are expected to behave. And third, people's motivations for sexual activity are by no means always and only for intrinsic pleasure. Human sexuality is influenced by a blend of biological, psychological, and cultural factors.

The Biology of Desire

In the middle of the last century, Alfred Kinsey and his associates (1948, 1953) published two pioneering books on male and female sexuality. Kinsey's team surveyed thousands of Americans from 1938 to 1963 about their sexual attitudes and behavior, and they also reviewed the existing research on sexual physiology. At that time, many people believed that women were not as sexually motivated as men and that women cared more about affection than sexual satisfaction, notions soundly refuted by Kinsey's interviews.

Kinsey was attacked not only for his findings, but also for even daring to ask people about their sexual lives. The national hysteria that accompanied the Kinsey Reports seems hard to believe today: “Danger Lurks In Kinsey Book!” screamed one headline. Yet it is still difficult for social scientists to conduct serious, methodologically sound research on the development of human sexuality. As John Bancroft, a leading sexologist, has observed, because many American adults need to believe that young children have no sexual feelings, they interpret any evidence of normal sexual expression in childhood (such as masturbation or “playing doctor”) as a symptom of sexual abuse. And because many adults are uncomfortable about sexual activity among teenagers, they try to restrict or eliminate it by prohibiting sex education and promoting abstinence, both of which actually increase rates of teenage sexuality and pregnancy (Bancroft, 2006; J. Levine, 2003; Trenholm et al., 2007). For an overview of historical and recent attitudes toward sexuality, watch the video The Power of Sex.

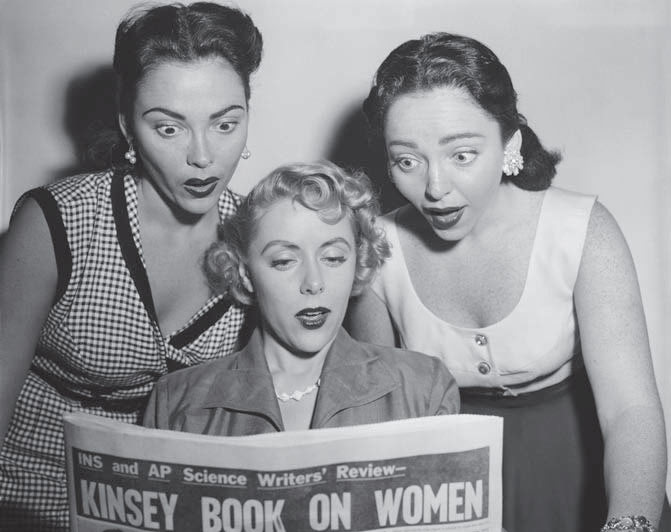

The “Kinsey Report on American Women” (though the book was actually titled Sexual Behavior in the Human Female) was not exactly greeted with praise and acceptance—or clear thinking. Cartoonists made fun of its being a “bombshell,” and in this 1953 photo, two famous jazz singers and an actress spoofed women's shock about the book—and their eagerness to read it.

Watch

The Power of Sex

Following Kinsey, the next wave of sex research began in the 1960s with the laboratory research of physician William Masters and his associate Virginia Johnson (1966). Masters and Johnson's research helped to sweep away cobwebs of superstition and ignorance about how the body works. In studies of physiological changes during sexual arousal and orgasm, they confirmed that male and female orgasms are remarkably similar and that all orgasms are physiologically the same, regardless of the source of stimulation.

If you have ever taken a sex education class, you may have had to memorize Masters and Johnson's description of the “four stages of the sexual response cycle”: desire, arousal (excitement), orgasm, and resolution. Unfortunately, the impulse to treat these four stages as if they were like the cycles of a washing machine led to a mistaken inference of universality. Not everyone has an orgasm even following great excitement, and in many women, desire follows arousal (Laan & Both, 2008). Masters and Johnson's research was limited by the selection of a sample consisting only of men and women who were easily orgasmic, and they did not investigate how people's physiological responses might vary according to age, experience, culture, and genetic predispositions (Tiefer, 2004). People vary not only in their propensity for sexual excitation and responsiveness, but also in their ability to inhibit and control that excitement (Bancroft et al., 2009). That is, some people are all accelerator and no brakes, and others are slow to accelerate but quick to brake.

Factors Promoting Sexual Desire One biological factor that promotes sexual desire in both sexes is the hormone testosterone, an androgen (masculinizing hormone). This fact has created a market for the legal and illegal use of androgens. The assumption is that if the goal is to increase sexual desire in women and men who complain of low libido, testosterone should be increased, like adding fuel to your gas tank; if the goal is to reduce sexual desire in sex offenders, testosterone should be lowered, perhaps through chemical castration. Yet these efforts often fail to produce the expected results (Berlin, 2003; M. Anderson, 2005). Why? A primary reason is that in primates, unlike other mammals, sexual motivation requires more than hormones; it is also affected by social experience and context (Randolph et al., 2014; Wallen, 2001). That is why desire can persist in sex offenders who have lost testosterone, and why desire might remain low in people who have been given testosterone. Indeed, artificially administered testosterone does not do much more than a placebo to increase sexual satisfaction in healthy people, nor does a drop in testosterone invariably cause a loss of sexual motivation or enjoyment. In studies of women who had had their uteruses or ovaries surgically removed or who were going through menopause, use of a testosterone patch increased their sexual activity to only one more time a month over the placebo group (Buster et al., 2005).

Men and Women: Same or Different? Despite the similarities in sexual response that Kinsey and then Masters and Johnson identified, the question of whether men and women are alike or different in some underlying, biologically based sex drive continues to provoke lively debate. Although women on average are certainly as capable as men of sexual pleasure, men do have higher rates of almost every kind of sexual behavior, including masturbation, erotic fantasies, casual sex, and orgasm (Peplau, 2003; Schmitt et al., 2012). These sex differences occur even when men are forbidden by cultural or religious rules to engage in sex at all; Catholic priests have more of these sexual experiences than Catholic nuns do (Baumeister, Catanese, & Vohs, 2001). Men are also more likely than women to admit to having sex because “the opportunity presented itself” (Meston & Buss, 2007).

Biological and evolutionary psychologists argue that these differences occur universally because the hormones and brain circuits involved in sexual behavior differ for men and women. They maintain that for men, the wiring for sex overlaps with that for dominance and aggression, which is why sex and aggression are more likely to be linked in men than in women. For women, the circuits and hormones governing sexuality and nurturance seem to overlap, which is why sex and love are more likely to be linked in women than in men (Diamond, 2008).

Other psychologists, however, believe that most gender differences in sexual behavior reflect women's and men's different roles and experiences in life (Ainsworth & Baumeister, 2012; Eagly & Wood, 1999; Tiefer, 2008). Women may have been more reluctant than men to have casual sex not because they have a lesser “drive” but because the experience is not as likely to be gratifying to them because of the greater risk of harm and risk of unwanted pregnancy, and because of the social stigma that may attach to women who have casual sex. Heterosexual women are just as likely as men to say they would accept a sexual offer from a great-looking person (or an unattractive famous person, which might explain the popularity of groupies). And both sexes are equally likely to say they would accept sex with friends or casual hook-ups who they think will be great lovers and give them a “positive sexual experience” (Conley et al., 2011; Rosin, 2012).

Of course, both views could be correct. It is possible that men's sexual behavior is more biologically influenced than is women's, increasing men's interest in having frequent, casual sex, whereas women's sexual desires and responsiveness are more affected by circumstances, the specific relationship, and cultural norms (Baumeister, 2000; Farr, Diamond, & Boker, 2014; Schmitt et al., 2012).

Implicit Associations Test

The Psychology of Desire

Psychologists are fond of observing that the sexiest sex organ is the brain, where perceptions begin. People's values, fantasies, and beliefs profoundly affect their sexual desire and behavior. That is why a touch on the knee by an exciting new date feels terrifically sexy, but the same touch by a creepy stranger on a bus feels disgusting. It is why a worried thought can kill sexual arousal in a second, and why a fantasy can be more erotic than reality.

The Many Motives for Sex To most people, the primary motives for sex are pretty obvious: to enjoy the pleasure of it, to express love and intimacy, or to make babies. But other motives are not so positive, including money or perks, duty or feelings of obligation, rebellion, power over the partner, and submission to the partner to avoid his or her anger or rejection.

The many motivations for sex range from sex for profit to sex for fun.

One survey of nearly 2,000 people yielded 237 motives for having sex, and nearly every one of them had been rated as the most important motive by someone. Most men and women listed the same top 10, including attraction to the partner, love, fun, and physical pleasure. But some said, “I wanted to feel closer to God,” “I was drunk,” “to get rid of a headache” (that was #173), “to help me fall asleep,” “to make my partner feel powerful,” “to return a favor,” “because someone dared me,” or “to hurt an enemy or a rival” (“I wanted to make him pay so I slept with his girlfriend”; “I wanted someone else to suffer from herpes as I do”). In this survey, men were more likely than women to say they use sex to gain status, enhance their reputation (e.g., because the partner was normally “out of my league”), or get things (such as a promotion) (Meston & Buss, 2007).

Across the many studies of motives for sex, there appear to be several major categories (Cooper, Shapiro, & Powers, 1998; Meston & Buss, 2007):

Pleasure: the satisfaction and physical pleasure of sex.

Intimacy: emotional closeness with the partner, spiritual transcendence.

Insecurity: reassurance that you are attractive or desirable.

Partner approval: the desire to please or appease the partner; the desire to avoid the partner's anger or rejection.

Peer approval: the wish to impress friends, be part of a group, and conform to what everyone else seems to be doing.

Attaining a goal: to get status, money, revenge, or “even the score.”

People's motives for having sex affect many aspects of their sexual behavior, including whether they engage in sex in the first place, whether they enjoy it, whether they have unprotected or otherwise risky sex, and whether they have few or many partners (Browning et al., 2000; Muise, Impett, & Desmarais, 2013; Snapp et al., 2014). Extrinsic motives, such as having sex to gain approval from others or get some tangible benefit, are most strongly associated with risky sexual behavior, including having many partners, not using birth control, and pressuring a partner into sex (Hamby & Koss, 2003). For men, extrinsic motives include peer pressure, inexperience, a desire for popularity, or a fear of seeming unmasculine. Women's extrinsic motives include not wanting to lose the relationship; feeling obligated after the partner had spent time and money on them; feeling guilty about not doing what the partner demands; or wanting to avoid conflict and quarrels (Impett, Gable, & Peplau, 2005).

When one partner is feeling insecure about the relationship, he or she is also more likely to consent to unwanted sex. In a study of 125 college women, one-half to two-thirds of the Asian American, white, and Latina women had consented to having sex when they didn't really want to, and all of the African American women said they had. Do you remember the attachment theory of love discussed earlier? Anxiously attached women were the most willing to consent to unwanted sex, especially if they feared their partners were less committed than they were. They reported that they often had sex out of feelings of obligation and to prevent the partner from leaving. Securely attached women also occasionally had unwanted sex, but their reasons were different: to gain sexual experience, to satisfy their curiosity, or to actively please their partners and further the intimacy between them (Impett, Gable, & Peplau, 2005).

Sexual Coercion and Rape One of the most persistent differences in the sexual experiences of women and men has to do with sexual coercion. A U.S. government survey of rape and domestic violence, based on a nationally representative sample of 16,507 adults, reported that nearly one in five women said they had been raped or experienced attempted rape at least once. (The researchers defined rape as completed or attempted forced penetration, including forced penetration enabled by alcohol or drugs.) The investigators also found high rates of aggression not usually measured in studies of rape, including coercive efforts to control the woman's reproductive and sexual health. Men also reported being victimized, but the numbers were much lower: One in seven said they had been severely beaten at the hands of a partner, and 1 to 2 percent said they had been raped, most when they were younger than age 11 (Black et al., 2011).

However, many women who report a sexual assault that meets the legal definition of rape—being forced to engage in sexual acts against their will—do not label it as such (McMullin & White, 2006; Peterson & Muehlenhard, 2011). Most women define “rape” as being forced into intercourse by an acquaintance or stranger, as an act that caused them to fight back, or as having been molested as a child. They are least likely to call their experience rape if they were sexually assaulted by a boyfriend, had previously had consensual sex with him, were drunk or otherwise drugged, or were forced to have oral sex or unwanted manual stimulation. Other women are motivated to avoid labeling the experience with such a charged word because they are embarrassed, or simply because they don't want to think of someone they know personally as being a “rapist” (Koss, 2011; Perilloux, Duntley, & Buss, 2014; Peterson & Muehlenhard, 2011).

What causes some men to rape? Evolutionary arguments—that rape stems from the male drive to fertilize as many females as possible, the better to distribute their genes—have not been supported (Buss & Schmitt, 2011). Among human beings, rape is often committed by high-status men, including sports heroes and other celebrities, who could easily find consenting sexual partners. All too frequently its victims are children or older adults, who do not reproduce. And sadistic rapists often injure or kill their victims, hardly a way to perpetuate one's genes. The human motives for rape thus appear to be primarily psychological, and include these:

Narcissism and hostility toward women. Sexually aggressive males often are narcissistic, are unable to empathize with women, and feel entitled to have sexual relations with whatever woman they choose. They misperceive women's behavior in social situations, equate feelings of power with sexuality, and accuse women of provoking them (Bushman et al., 2003; Malamuth et al., 1995; Widman & McNulty, 2010).

A desire to dominate, humiliate, or punish the victim. This motive is apparent among soldiers who rape captive women during war and then often kill them (Olujic, 1998). Similarly, reports of the systematic rapes of female cadets at the U.S. Air Force Academy suggest that the rapists' motives were to humiliate the women and get them to drop out. Aggressive motives also occur in the rape of men by other men, usually by anal penetration (King & Woollett, 1997). This form of rape typically occurs in youth gangs, where the intention is to humiliate rival gang members, and in prison, where again the motive is to conquer and degrade the victim.

Sadism. A minority of rapists are violent criminals who get pleasure out of inflicting pain on their victims and who often murder them in planned, grotesque ways (Healey, Lussier, & Beauregard, 2013; Turvey, 2008).

You can see that the answer to the question “Why do people have sex?” is not a simple matter of “doing what's natural.” In addition to the intrinsic motives of intimacy, pleasure, procreation, and love, extrinsic motives include intimidation, dominance, insecurity, appeasing the partner, approval from peers, and the wish to prove oneself a real man or a desirable woman.

Gender, Culture, and Sex

Think about kissing. Westerners like to think about kissing, and to do it, too. But if you think kissing is natural, try to remember your first serious kiss and all you had to learn about noses, breathing, and the position of teeth and tongue. The sexual kiss is so complicated that some cultures have never gotten around to it. They think that kissing another person's mouth—the very place that food enters!—is disgusting (Tiefer, 2004). Others have elevated the sexual kiss to high art; why do you suppose one version is called French kissing?

As the kiss illustrates, simply having the physical equipment to perform a sexual act is not enough to explain sexual motivation. People have to learn what is supposed to turn them on (or off), which parts of the body and what activities are erotic (or repulsive), and even how to have pleasurable sexual relations. In some cultures, oral sex is regarded as a bizarre sexual deviation; in others, it is considered not only normal but also supremely desirable. In many cultures, men believe that women who have experienced sexual pleasure of any kind will become unfaithful, so sexual relations are limited to quick intercourse; in other cultures, men's satisfaction and pride depend on knowing the woman is sexually satisfied too. In some cultures, sex itself is seen as something joyful and beautiful, an art to be cultivated as one might cultivate the skill of gourmet cooking. In others, it is considered ugly and dirty, something to be gotten through as rapidly as possible. These differences in perceptions are explored further in the video Cultural Norms and Sexual Behavior.

Watch

Cultural Norms and Sexual Behavior

How do cultures transmit their rules and requirements about sex to their members? During childhood and adolescence, people learn their culture's gender roles, collections of rules that determine the proper attitudes and behavior for men and women. Like an actor in a play, a person following a gender role relies on a sexual script that provides instructions on how to behave in sexual situations (Gagnon & Simon, 1973; Sakaluk et al., 2014). If you are a teenage girl, are you supposed to be sexually adventurous and assertive or sexually modest and passive? What if you are a teenage boy? What if you are an older woman or man? The answers differ from culture to culture, as members act in accordance with the sexual scripts for their gender, age, sexual orientation, religion, social status, and peer group.

These teenagers are following the sexual scripts for their gender and culture—the boys by ogling and making sexual remarks about girls to impress their peers, and the girls by preening and wearing makeup to look attractive.

In many parts of the world, boys acquire their attitudes about sex in a competitive atmosphere where the goal is to impress other males, and they talk and joke about masturbation and other sexual experiences with their friends. Although their traditional sexual scripts are encouraging them to value physical sex, traditional scripts are teaching girls to value relationships and make themselves attractive (Matlin, 2012). At an early age, girls learn that the closer they match the cultural ideal of beauty, the greater their power, sexually and in other ways. They learn that they will be scrutinized and evaluated according to their looks, which of course is the meaning of being a “sex object” (Impett et al., 2011). What many girls and women may not realize is that the more sexualized their clothing, the more likely they are to be seen as incompetent and unintelligent (Graff, Murnen, & Smolak, 2012; Montemurro & Gillen, 2013).

Scripts can be powerful determinants of behavior, including the practice of safe sex to reduce the risk of unwanted pregnancy or sexually transmitted diseases. In interviews with black women ages 22 to 39, researchers found that a reduced likelihood of practicing safe sex was associated with scripts fostering the beliefs that men control relationships; women sustain relationships; male infidelity is normal; men control sexual activity; women want to use condoms, but men control condom use (Bowleg, Lucas, & Tschann, 2004). As one woman summarized, “The ball was always in his court.” These scripts, the researchers noted, were rooted in African American history and the recurring scarcity of men available for long-term commitments. The scripts originated to preserve the stability of the family, but they encourage some women to maintain sexual relationships at the expense of their own needs and safety.

Today, however, the scripts are changing, largely as a result of women's improving economic status. The ball is no longer always in the man's court, and as a result, girls and young women increasingly feel free to control their own sexual lives (Rosin, 2012). Whenever women have needed marriage to ensure their social and financial security, they have regarded sex as a bargaining chip, an asset to be rationed rather than an activity to be enjoyed for its own sake. After all, a woman with no economic resources of her own cannot afford to casually seek sexual pleasure if that means risking an unwanted pregnancy, the security of marriage, her reputation in society, her physical safety, or, in some cultures, her very life. When women become better educated, self-supporting, and able to control their own fertility—three major worldwide changes that began in the last half of the 20th century—they are more likely to want sex for pleasure rather than as a means to another goal.

In the TV series Girls, the friends include a virgin, a sexual adventurer, and a heroine looking for love and sex with one man. This rewriting of the traditional sexual script for women, and the easy, explicit way the girls talk about sex, has drawn both fans and critics.

In the United States, young people's sexual attitudes and behavior changed dramatically between 1943 and 1999: For example, approval of premarital sex leapt from 12 percent to 73 percent among young women, and from 40 percent to 79 percent among young men (Wells & Twenge, 2005). Conversely, when women are not financially dependent on men and have goals of economic self-sufficiency, it is easier for them to refuse sex as well as to leave an abusive relationship or situation. By 2010, the percentage of girls ages 15–17 who had had sexual intercourse dropped from 37.2 to 27; teen pregnancies and reports of acquaintance rape also reached a record low (Hamilton et al., 2015).

Gender and Sexuality Survey