13.1

From Conception Through the First Year

A baby's development, before and after birth, is a marvel of maturation, the sequential unfolding of genetically influenced behavior and physical characteristics. In only 9 months of a mother's pregnancy, a cell grows from a dot this big (.) to a squealing bundle of energy who looks just like Aunt Norma. In another 15 months, that bundle of energy grows into a babbling toddler who is curious about everything. No other time in human development brings so many changes so fast.

[[For Revel: Insert Interactive 13.1]]

Prenatal Development

Prenatal development begins at fertilization, when the male sperm unites with the female ovum (egg) to form a single-celled egg called a zygote. The zygote soon begins to divide, and in 10 to 14 days, it has become a cluster of cells that attaches itself to the wall of the uterus. The outer portion of this cluster will form part of the placenta and umbilical cord, and when implantation is completed about 2 weeks after fertilization, the inner portion becomes the embryo. The placenta, connected to the embryo by the umbilical cord, serves as the growing embryo's link for food from the mother. It allows nutrients to enter and wastes to exit, and it screens out some, but not all, harmful substances. At 8 weeks after conception, the embryo is only 1½ inches long. During the fourth to eighth weeks, the hormone testosterone is secreted by the rudimentary testes in embryos that are genetically male; without this hormone, the embryo will develop to be anatomically female. After 8 weeks, the organism, now called a fetus, further develops the organs and systems that existed in rudimentary form in the embryonic stage. Watch the video Sex and Gender Differences 1 to learn more about how a fetus develops into a female or a male.

Ordinary Babies

Watch

Sex and Gender Differences 1

Although the womb is a fairly sturdy protector of the growing embryo or fetus, the prenatal environment—which is influenced by the mother's own health, genetic predispositions, allergies, and diet—can affect the course of development, as by predisposing an infant to later obesity or immune problems (Coe & Lubach, 2008). Most people don't realize it, but fathers play a role in prenatal development, too. Because of genetic mutations in sperm, fathers over age 50 have three times the risk of conceiving a child who develops schizophrenia as fathers under age 25 do (Goriely et al., 2013); teenage fathers have an increased risk that their babies will be born prematurely or have low birth weight; babies of men exposed to solvents and other chemicals in the workplace are more likely to be miscarried or stillborn, or to develop cancer later in life; and having an older father increases the probability that a child will have autism or bipolar disorder (Frans et al., 2008; Kong et al., 2012; Sandin et al., 2014).

During a woman's pregnancy, some harmful influences can cross the placental barrier and affect the fetus (O'Rahilly & Müller, 2001). These influences include:

German measles (rubella), especially early in the pregnancy, can affect the fetus's eyes, ears, and heart. The most common consequence is deafness. Rubella is preventable if the mother has been vaccinated, which can be done up to 3 months before pregnancy.

X-rays or other radiation, pollutants, and toxic substances can cause fetal deformities and cognitive abnormalities that can last throughout life. Exposure to lead is associated with attention problems and lower IQ scores, as is exposure to mercury (found most commonly in contaminated fish), pesticides, and high air pollution (Newland & Rasmussen, 2003; Perera et al., 2013; Raloff, 2011).

Sexually transmitted diseases can cause mental retardation, blindness, and other physical disorders. Genital herpes affects the fetus only if the mother has an outbreak at the time of delivery, which exposes the newborn to the virus as the baby passes through the birth canal. (This risk can be avoided by having a cesarean section.) HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, can also be transmitted to the fetus, especially if the mother has developed AIDS and has not been treated.

Cigarette smoking during pregnancy increases the likelihood of miscarriage, premature birth, an abnormal fetal heartbeat, and an underweight baby. The negative effects may last long after birth, showing up in increased rates of infant sickness, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), and, in later childhood, hyperactivity, learning difficulties, asthma, and even antisocial behavior (Button, Thapar, & McGuffin, 2005; Chudal et al., 2015).

Maternal stress can affect the fetus, increasing the risk of later cognitive and emotional problems and vulnerability to adult diseases such as hypertension (Ping et al., 2015; Talge, Neal, & Glover, 2007). Babies of mothers who developed posttraumatic stress disorder in the aftermath of the World Trade Center attacks on 9/11 were more likely to have abnormal cortisol levels themselves at 1 year of age, and also to weigh less at birth, both indicators of future health problems (Yehuda et al., 2005).

Drugs can be harmful to the fetus, whether they are illicit ones such as cocaine and heroin, or legal substances such as alcohol, antibiotics, antidepressants, antihistamines, tranquilizers, acne medication, prescription opiate painkillers, and diet pills (Healy, 2012; Lester, LaGasse, & Seifer, 1998; Stanwood & Levitt, 2001). Regular consumption of alcohol can kill neurons throughout the fetus's developing brain and impair the child's later mental abilities, attention span, and academic achievement (Gautam et al., 2015; Streissguth, 2001). Having more than two drinks a day significantly increases the risk of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), which is associated with low birth weight, a smaller brain, facial deformities, lack of coordination, and mental retardation.

In addition to avoiding these teratogens, a pregnant woman can do much to have a healthy baby. She can maintain a healthy weight, take prenatal vitamins (especially folic acid, which prevents neural defects in the brain and spinal cord), and get regular prenatal care (Abu-Saad & Fraser, 2010).

The Infant's World

Newborn babies could never survive on their own, but they are far from being passive and inert. Many abilities, tendencies, and characteristics are universal in human beings and are present at birth or develop very early, given certain experiences. Newborns begin life with several motor reflexes, automatic behaviors that are necessary for survival. They will suck on anything suckable, such as a nipple or finger. They will grasp tightly a finger pressed on their tiny palms. They will turn their heads toward a touch on the cheek or corner of the mouth and search for something to suck on, a handy rooting reflex that allows them to find the breast or bottle. Many of these reflexes eventually disappear, but others—such as the knee-jerk, eyeblink, and sneeze reflexes—remain.

Infants are born with a grasping reflex; they will cling to any offered finger. And they need the comfort of touch, which their adult caregivers love to provide.

Babies are also equipped with a set of inborn perceptual abilities. They can see, hear, touch, smell, and taste (bananas and sugar water are in, rotten eggs are out; Steiner, 1973). A newborn's visual focus range is only about 8 inches, the average distance between the baby and the face of the person holding the baby, but visual ability develops rapidly. Newborns can distinguish contrasts, shadows, and edges. And they can discriminate their mother or other primary caregiver on the basis of smell, sight, or sound almost immediately. Even more impressive, babies are born with an interest in novelty and some basic cognitive skills, including a fundamental sense of number (they know that three things are more than two things) (Izard et al., 2009).

Experience, however, plays a crucial role in shaping an infant's mind, brain, and gene expression right from the get-go. Infants who get little touching will grow more slowly and release less growth hormone than their amply cuddled peers, and throughout their lives, they have stronger reactions to stress and are more prone to depression and its cognitive deficits (Diamond & Amso, 2008; Field, 2009). Although infants everywhere develop according to the same maturational sequence, many aspects of their development depend on cultural customs that govern how their parents hold, touch, feed, and talk to them (Rogoff, 2003). In the United States, Canada, and most European countries, babies are expected to sleep for eight uninterrupted hours by the age of 4 or 5 months. This milestone is considered a sign of neurological maturity, although many babies wail when the parent puts them in the crib at night and leaves the room. But among Mayan Indians, rural Italians, African villagers, Indian Rajput villagers, and urban Japanese, this nightly clash of wills rarely occurs because the infant sleeps with the mother for the first few years of life, waking and nursing about every 4 hours. These differences in babies' sleep arrangements reflect cultural and parental values. Mothers in these cultures believe it is important to sleep with the baby so that both will forge a close bond; in contrast, many urban North American and German parents believe it is important to foster the child's independence as soon as possible (Super & Harkness, 2013).

Attachment

Emotional attachment is a universal capacity of all primates and is crucial for health and survival all through life. The mother is usually the first and primary object of attachment for an infant, but in many cultures (and other species), babies become just as attached to their fathers, siblings, and grandparents (Hrdy, 1999; Shwalb & Shwalb, 2015).

Interest in the importance of early attachment began with the work of British psychiatrist John Bowlby (1969, 1973), who observed the devastating effects on babies raised in orphanages without touches or snuggling, and on other children raised in conditions of severe deprivation or neglect. The babies were physically healthy but emotionally despairing, remote, and listless. By becoming attached to their caregivers, Bowlby said, children gain a secure base from which they can explore the environment and a haven of safety to return to when they are afraid. Ideally, infants will find a balance between feeling securely attached to the caregiver and feeling free to explore and learn in new environments.

Contact Comfort Attachment begins with physical touching and cuddling between infant and parent. Contact comfort, the pleasure of being touched and held, is crucial not only for newborns, but also for everyone throughout life because it releases a flood of pleasure-producing and stress-reducing endorphins (Rilling & Young, 2014). In hospital settings, even the mildest touch by a nurse or physician on a patient's arm or forehead is reassuring psychologically and lowers blood pressure.

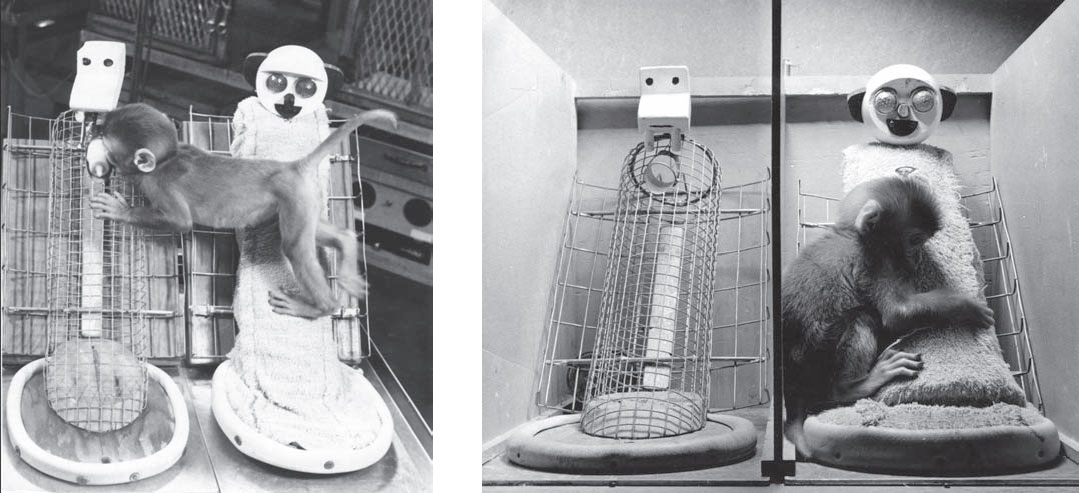

Margaret and Harry Harlow first demonstrated the importance of contact comfort by raising infant rhesus monkeys with two kinds of artificial mothers (Harlow, 1958; Harlow & Harlow, 1966). One, which they called the “wire mother,” was a forbidding construction of wires and warming lights, with a milk bottle connected to it. The other, the “cloth mother,” was constructed of wire but covered in foam rubber and cuddly terry cloth (see Figure13.1). At the time, many psychologists thought that babies become attached to their mothers simply because mothers provide food (Blum, 2002). But the Harlows' baby monkeys ran to the terry-cloth mother when they were frightened or startled, and snuggling up to it calmed them down. Human children also seek contact comfort when they are in an unfamiliar situation, are scared by a nightmare, or fall and hurt themselves.

Figure 13.1

The Comfort of Contact

Infants need cuddling as much as they need food. In Margaret and Harry Harlows studies, infant rhesus monkeys were reared with a cuddly terry-cloth "mother" and with a bare wire "mother" that provided milk. The infants would cling to the terry-cloth mother when they were not being fed. But when an unfamiliar and scary toy (a mechanical spider or a large teddy bear) was placed in the enclosure, the infant monkey would run to the terry-cloth mother for comfort. Only when reassured by that contact comfort would the infant venture back out to examine the toy.

Separation and Security After babies have become emotionally attached to the mother or other caregiver, separation can be a wrenching experience. Between 6 and 8 months of age, babies become wary or fearful of strangers. They wail if they are put in an unfamiliar setting or are left with an unfamiliar person. And they show separation anxiety if the primary caregiver temporarily leaves them. This reaction usually continues until the middle of the second year, but many children show signs of distress until they are about 3 years old (Hrdy, 1999). All children go through this phase, although cultural childrearing practices influence how strongly the anxiety is felt and how long it lasts (see Figure13.2). In cultures where babies are raised with lots of adults and other children, separation anxiety is not as intense or as long-lasting as it can be in cultures where babies form attachments primarily or exclusively with the mother (Rothbaum, Morelli, & Rusk, 2011).

Figure 13.2

The Rise and Fall of Separation Anxiety

At around 6 months of age, many babies begin to show separation anxiety when the person who is their main source of attachment tries handing them over to someone else or leaves the room. This anxiety typically peaks at about a year of age and then steadily declines. But the proportion of children responding this way varies across cultures. It is high among rural African children and low among children raised in a communal Israeli kibbutz, where children become attached to many adults. (Data from Kagan, Kearsley, & Zelazo, 1978.)

To study the nature of the attachment between mothers and babies, Mary Ainsworth (1973, 1979) devised an experimental method called the Strange Situation. A mother brings her baby into an unfamiliar room containing lots of toys. After a while, a stranger comes in and attempts to play with the child. The mother leaves the baby with the stranger. She then returns and plays with the child, and the stranger leaves. Finally, the mother leaves the baby alone for 3 minutes and returns. In each case, observers note how the baby behaves with the mother, with the stranger, and when the baby is alone.

Ainsworth divided the children into categories on the basis of their reactions to the Strange Situation. Some babies were securely attached: They cried or protested when the parent left the room; they welcomed her back and then played happily again; they were clearly more attached to the mother than to the stranger. Other babies were insecurely attached, and this insecurity took one of two forms. Some children were avoidant, not caring if the mother left the room, making little effort to seek contact with her upon her return, and treating the stranger about the same as the mother. Other insecure children were anxious or ambivalent, resisting contact with the mother at reunion but protesting loudly if she left. Some anxious-ambivalent babies cried to be picked up and then demanded to be put down; others behaved as if they were angry with the mother and resisted her efforts to comfort them. Attachment theory is explored in more detail in the video Attachment.

Watch

Attachment

What Causes Insecure Attachment? Ainsworth believed that the difference between secure, avoidant, and anxious-ambivalent attachment lies primarily in the way mothers treat their babies during the first year. Mothers who are sensitive and responsive to their babies' needs, she said, create securely attached infants; mothers who are uncomfortable with or insensitive to their babies create insecurely attached infants. To many, the implication was that babies needed exactly the right kind of mothering from the very start in order to become securely attached, and that putting a child in daycare would retard this development—notions that have caused considerable insecurity among mothers!

Ainsworth's measure of attachment, however, did not take the baby's experience into account. Babies who become attached to many adults, because they live in large extended families or have spent a lot of time with adults in daycare, may seem to be avoidant in the Strange Situation because they don't panic when their mothers leave. But perhaps they have simply learned to be comfortable with strangers. Moreover, although a small correlation exists between a mother's sensitivity to her child and the security of her child's attachment, this doesn't tell us which causes which, or whether something else causes both sensitivity and secure attachment. Programs designed to help new mothers become less anxious and more attuned to their babies do help some moms become more sensitive, but these programs only modestly affect the child's degree of secure attachment (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2008).

The emphasis on maternal sensitivity also overlooks the fact that most children, all over the world, form a secure attachment to their mothers in spite of wide variations in childrearing practices (LeVine & Norman, 2008; Mercer, 2006). German babies are frequently left on their own for a few hours at a stretch by mothers who believe that even babies should become self-reliant. And among the Efe of Africa, babies spend about half their time away from their mothers in the care of older children and other adults (Tronick, Morelli, & Ivey, 1992). Yet German and Efe children are not insecure, and they develop as normally as children who spend more time with their mother. Likewise, time spent in daycare—10 hours a week to more than 30—has no effect on the security of a child's attachment (Oliviera et al., 2015; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2006).

What factors, then, do promote insecure attachment?

Abandonment and deprivation in the first year or two of life. Institutionalized babies are more likely than adopted children to have later problems with attachment, whereas babies adopted before age 1 or 2 eventually become as securely attached as any other children (Lionetti, Pastore, & Barone, 2015; van den Dries et al., 2009; Vorria et al., 2015).

Parenting that is abusive, neglectful, or erratic because the parent is chronically irresponsible or clinically depressed. A South African research team observed 147 mothers with their 2-month-old infants and followed up when the babies were 18 months old. Many of the mothers who had suffered from postpartum depression became either too intrusive with their infants or too remote and insensitive. In turn, their babies were more likely to be insecurely attached at 18 months (Tomlinson, Cooper, & Murray, 2005).

The child's own genetically influenced temperament. Babies who are fearful and prone to crying from birth are more likely to show insecure behavior in the Strange Situation, suggesting that their later insecure attachment may reflect a temperamental predisposition (Gillath et al., 2008; Khoury et al., 2015; Seifer et al., 1996).

Longitudinal studies find that good daycare does not affect the security of children’s attachments and often produces many social and intellectual benefits.

Stressful circumstances in the child's family. Infants and young children may temporarily shift from secure to insecure attachment, becoming clingy and fearful of being left alone, if their families are undergoing a period of stress, as during parental divorce or a parent's chronic illness (Belsky et al., 1996; Mercer, 2006).

The bottom line, however, is that infants are biologically disposed to become attached to their caregivers. Normal, healthy attachment will occur within a wide range of cultural, family, and individual variations in childrearing customs. Although, sadly, things can go wrong in prenatal development and in the first year after birth, the plasticity of the brain and human resilience can often overcome early deprivation or even harm.

What Has Your Father Done For You?