13.2

Cognitive Development

A friend of ours told us about a charming exchange he had with his 2-year-old grandson. “You're very old,” the little boy said. “Yes, I am,” said his grandfather. “I'm very new,” said the child. Two years old, and already this little boy's mind is working away, making observations, trying to understand the differences he observes, and using language (creatively!) to describe them. The development of language and thought from infancy throughout childhood is a marvel to anyone who has ever watched a baby grow up. In this section we'll explore how these processes take place.

Language

Try to read this sentence aloud:

Kamaunawezakusomamanenohayawewenimtuwamaanasana.

Can you tell where one word begins and another ends? Unless you know Swahili, the syllables of this sentence will sound like gibberish.1

Well, to a baby learning its native tongue, every sentence must be gibberish at first. How, then, does an infant pick out discrete syllables and words from the jumble of sounds in the environment, much less figure out what the words mean? And how is it that within a few years, children not only understand thousands of words but can also produce and understand an endless number of new word combinations?

To answer, we must first appreciate that a language is not just any old communication system; it is a set of rules for combining inherently meaningless elements into utterances that convey meaning. The elements are usually sounds, but they can also be the gestures of American Sign Language (ASL) and other manual languages that deaf and hearing-impaired people use. Because of language, we can refer not only to the here and now but also to past and future events, and to things or people who are not present. Furthermore, language, whether spoken or signed, allows human beings to express and comprehend an infinite number of novel utterances, created on the spot. This ability is critical; except for a few fixed phrases (“How are you?” “Get a life!”), most of the utterances we produce or hear over a lifetime are new. How in the world do we do this?

Language: Built in or Learned? Many psychological scientists believe that an innate facility for language evolved in human beings because it was extraordinarily beneficial (Pinker, 1994, 2013). It permitted our prehistoric ancestors to convey precise information about time, space, and events (as in “Honey, are you going on the mammoth hunt today?”) and allowed them to negotiate alliances that were necessary for survival (“If you share your nuts and berries with us, we'll share our mammoth with you”). Language may also have developed because it provides the human equivalent of the mutual grooming that other primates rely on to forge social bonds (Dunbar, 2004; Tomasello, 2008). Just as other primates will clean, stroke, and groom one another for hours as a sign of affection and connection, human friends will sit for hours and chat over coffee.

At one time, the leading theory held that children acquired language by imitating adults and paying attention when adults corrected their mistakes. Then along came linguist Noam Chomsky (1957, 1980, 2015), who argued that language was far too complex to be learned bit by bit, as one might learn a list of world capitals. Because no one actually teaches us grammar when we are toddlers, said Chomsky, the human brain must contain an innate mental module—a universal grammar—that allows young children to develop language if they are exposed to an adequate sampling of conversation. Their brains are sensitive to the core features common to all languages, such as nouns and verbs, subjects and objects, and negatives. These common features occur even in languages as seemingly different as Mohawk and English, or Okinawan and Bulgarian (Baker, 2001; Cinque, 1999; Nevins, Pesetsky, & Rodrigues, 2009). In English, even 2-year-olds use syntax to help them acquire new verbs in context: They understand that “Jane blicked the baby!” involves two people, but the use of the same verb in “Jane blicked!” involves only Jane (Dautriche et al., 2014; Yuan & Fisher, 2009).

Evidence for Chomsky's theory that humans have an innate mental module for language comes from several directions. Children in different cultures go through similar stages of linguistic development, and they combine words in ways that adults never would. They reduce a parent's sentences (“Let's go to the store!”) to their own two-word versions (“Go store!”) and make many charming errors that an adult would not (“The alligator goed kerplunk,” “Hey, Horton heared a Who”) (Ervin-Tripp, 1964; Marcus et al., 1992). Adults do not consistently correct their children's syntax, yet children learn to speak or sign correctly anyway. Parents may even reward children for syntactically incorrect or incomplete sentences: The 2-year-old who says “Want milk!” is likely to get it; most parents would not wait for a more grammatical (or polite) request.

Most compelling, deaf children who have never learned a standard language, either signed or spoken, have made up their own sign languages out of thin air, and these languages often show similarities in sentence structure across countries as varied as the United States, Taiwan, Spain, and Turkey (Fay et al., 2014; Goldin-Meadow, 2003). The most astounding case comes from Nicaragua, where a group of deaf children, attending special schools, created a homegrown but grammatically complex sign language that is unrelated to Spanish (Senghas, Kita, & Özyürek, 2004). Scientists have had a unique opportunity to observe the evolution of this language as it developed from a few simple signs to a full-blown linguistic system.

These deaf Nicaraguan children have invented their own grammatically complex sign language, one that is unrelated to Spanish or to any conventional gestural language (Senghas, Kita, & Özyürek, 2004).

However, in the last decade, psycholinguists have taken aim at Chomsky's view, and many now believe that the assumption of a universal grammar is simply wrong (Dunn et al., 2011; Evans & Levinson, 2009; Hinzen, 2014; Tomasello, 2003). In spite of commonalities in language acquisition around the world, the world's 7,000 languages have some major differences that do not seem explainable by a universal grammar (Gopnik, Choi, & Bamberger, 1996). The language spoken by the remote Pirahã in the Amazon and the Wari' language of Brazil apparently lack key grammatical features that occur in other languages (Everett, 2012). One team constructed an evolutionary history for four major language groups and found that each group followed its own structural rules, suggesting that human language is driven by cultural requirements rather than an innate grammar (Dunn et al., 2011; Majid, Jordan, & Dunn, 2014). The anti-innate-module school argues that language is a cultural tool, comparable to the physical tools that people have invented in adapting to different physical and cultural environments. Culture, they say, is the primary determinant of a language's linguistic structure, not an innate grammar.

Experience and culture certainly play a large role in language development. Parents may not go around correcting their children's speech all day, but they do recast and expand their children's clumsy or ungrammatical sentences (“Monkey climbing!” “Yes, the monkey is climbing the tree”). Children, in turn, often imitate those recasts and expansions, indicating that they are learning from them (Bohannon & Symons, 1988).

Some scientists argue that instead of inferring grammatical rules because of an innate disposition to do so, children learn the probability that any given word or syllable will follow another, something infants as young as 8 months are able to do (Seidenberg, MacDonald, & Saffran, 2002). Because so many word combinations are used repeatedly (“Pick up your socks!” “Come to dinner!”), little kids seem able to track short word sequences and their frequencies, which in turn plays a role in teaching them not only vocabulary but syntax (Arnon & Clark, 2011). Eventually, children also learn how nonadjacent words co-occur (e.g., the and ducky in “the yellow ducky”), and are able to generalize their knowledge to learn syntactic categories (Gerken, Wilson, & Lewis, 2005; Lany & Gómez, 2008).

In this view, infants are more like statisticians than grammarians, and their “statistics” are based on experience. Using computers, these theorists have designed mathematical models of the brain that can acquire some aspects of language, such as regular and irregular past-tense verbs, without the help of a preexisting mental module or preprogrammed rules. These computer programs, called computer neural networks, simply adjust the connections among hypothetical neurons in response to incoming data, such as repetitions of a word in its past-tense form. The success of these computer models, say their designers, suggests that children, too, may be able to acquire linguistic features without getting a head start from inborn brain modules (Rodriguez, Wiles, & Elman, 1999; Tomasello, 2008).

Although the argument between the Chomsky school and the culture school continues, both sides agree that language development depends on both biological readiness and social experience. Children who are not exposed to language during their early years rarely speak normally or catch up grammatically. Such sad evidence suggests a critical period in language development during the first few years of life or possibly the first decade. During these years, children need exposure to language and opportunities to practice their emerging linguistic skills in conversation with others. Let's see how these skills develop.

From Cooing to Communicating The acquisition of language may begin in the womb. Canadian psychologists tested newborn babies' preference for hearing English or Tagalog (a major language of the Philippines) by measuring the number of times the babies sucked on a rubber nipple—a measure of babies' interest in a stimulus—while hearing each language alternating during a 10-minute span. Those whose mothers spoke only English during pregnancy showed a clear preference for English by sucking more during the minutes when English was spoken. Those whose bilingual mothers spoke both languages showed equal preference for both languages (Byers-Heinlein, Burns, & Werker, 2010; Fennell & Byers-Heinlein, 2014).

Thus, infants are already responsive to the pitch, intensity, and sound of language, and they also react to the emotions and rhythms in voices. Adults take advantage of these infant abilities by speaking baby talk, called parentese. When most people speak to babies, their pitch is higher and more varied than usual and their intonation and emphasis on vowels are exaggerated. Parents all over the world do this. Adult members of the Shuar, a nonliterate hunter-gatherer culture in South America, can accurately distinguish American mothers' infant-directed speech from their adult-directed speech just by tone (Bryant & Barrett, 2007). Parentese helps babies learn the melody and rhythm of their native language.

In what has to have been one of the most adorable research projects ever, three investigators compared the way mothers spoke to their babies and to pets, which also tend to evoke baby talk. The mothers exaggerated vowel sounds for their babies but not for Noodles the poodle or Chubby the cat, suggesting that parentese is, indeed, a way of helping infants acquire language (Burnham, Kitamura, & Vollmer-Conna, 2002).

By 4 to 6 months of age, babies can often recognize their own names and other words that are regularly spoken with emotion, such as “mommy” and “daddy.” They also know many of the key consonant and vowel sounds of their native language and can distinguish such sounds from those of other languages (Kuhl et al., 1992). Then, over time, exposure to the baby's native language reduces the child's ability to perceive speech sounds that do not exist in their own. Thus, Japanese infants can hear the difference between the English sounds la and ra, but older Japanese children cannot. Because this contrast does not exist in their language, they become insensitive to it.

Between 6 months and 1 year, infants become increasingly familiar with the sound structure of their native language. They are able to distinguish words from the flow of speech. They will listen longer to words that violate their expectations of what words should sound like and even to sentences that violate their expectations of how sentences should be structured (Jusczyk, 2002). They start to babble, making many “ba-ba” and “goo-goo” sounds, endlessly repeating sounds and syllables. At 7 months, they begin to remember words they have heard, but because they are also attending to the speaker's intonation, speaking rate, and volume, they cannot always recognize the same word when different people speak it (Houston & Jusczyk, 2003). Then, by 10 months, they can suddenly do it—a remarkable leap forward in only 3 months. And at about 1 year of age, though the timing varies considerably, children take another giant step: They start to name things. They already have some concepts in their minds for familiar people and objects, and their first words represent these concepts (“mama,” “doggie,” “truck”).

Also at the end of the first year, babies develop a repertoire of symbolic gestures. They gesture to refer to objects (e.g., sniffing to indicate “flower”), to request something (smacking the lips for “food”), to describe objects (raising the arms for “big”), and to reply to questions (opening the palms or shrugging the shoulders for “I don't know”). They clap in response to pictures of things they like. Children whose parents encourage them to use gestures acquire larger vocabularies, have better comprehension, are better listeners, and are less frustrated in their efforts to communicate than children who are not encouraged to use gestures (Goodwyn & Acredolo, 1998). When babies begin to speak, they continue to gesture along with their words, just as adults often gesture when talking. These gestures are not a substitute for language but are deeply related to its development, as well as to the development of thinking and problem solving (Fay et al, 2014; Goldin-Meadow, Cook, & Mitchell, 2009). Parents, in turn, use gesture (pointing, touching, tapping) to capture their babies' attention and teach them the meanings of words (Clark & Estigarribia, 2011).

Symbolic gestures emerge early!

One surprising discovery is that babies who are given infant “brain stimulation” videos to look at do not learn more words than a control group, and often they are actually slower at acquiring words than babies who do not watch videos. For every hour a day that 8- to 16-month-old babies watch one of these videos, they acquire six to eight fewer words than other children (DeLoache et al., 2010; Zimmerman, Christakis, & Meltzoff, 2007). However, the more that parents read and talk to their babies and infants, the larger the child's vocabulary at age 3 and the faster the child processes familiar words (Weisleder & Fernald, 2013).

Between the ages of 18 months and 2 years, toddlers begin to produce words in two- or three-word combinations (“Mama here,” “go 'way bug,” “my toy”). The child's first combinations of words have been described as telegraphic speech. When people had to pay for every word in a telegram, they quickly learned to drop unnecessary articles (a, an, or the) and auxiliary verbs (is or are). Similarly, the two-word sentences of toddlers omit articles, word endings, auxiliary verbs, and other parts of speech, yet these sentences are remarkably accurate in conveying meaning. Children use two-word sentences to locate things (“there toy”), make demands (“more milk”), negate actions (“no want,” “all gone milk”), describe events (“Bambi go,” “hit ball”), describe objects (“pretty dress”), show possession (“Mama dress”), and ask questions (“where Daddy?”). Pretty good for a little kid, don't you think?

By the age of 6, the average child has a vocabulary of between 8,000 and 14,000 words, meaning that children acquire several new words a day between the ages of 2 and 6. They absorb new words as they hear them, inferring their meaning from their knowledge of grammatical contexts and from the social contexts in which they hear the words used (Golinkoff & Hirsh-Pasek, 2006; Rice, 1990).

Thinking

Children do not think the way adults do. For most of the first year of life, if something is out of sight, it's out of mind: If you cover a baby's favorite rattle with a cloth, the baby thinks the rattle has vanished and stops looking for it. And a 4-year-old may protest that a sibling has more fruit juice when it is only the shapes of the glasses that differ, not the amount of juice. Some truths and myths regarding childhood cognition are explored in the video Smart Babies by Design.

Watch

Smart Babies by Design

Yet children are smart in their own way. Like good little scientists, children are always testing their child-sized theories about how things work (Gopnik, Griffiths, & Lucas, 2015). When your toddler throws her spoon on the floor for the sixth time as you try to feed her, and you say, “That's enough! I will not pick up your spoon again!” the child will immediately test your claim. Are you serious? Are you angry? What will happen if she throws the spoon again? She is not doing this to drive you crazy; rather, she is learning that her desires and yours can differ, and that sometimes those differences are important and sometimes they are not.

How and why does children's thinking change? In the 1920s, Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget [Zhan Pee-ah-ZHAY] (1896–1980) proposed that children's cognitive abilities unfold naturally, like the blooming of a flower, almost independent of what else is happening in their lives. Although many of his specific conclusions have been rejected or modified over the years, his ideas inspired thousands of studies by investigators all over the world.

Like a good little scientist, this child is trying to figure out cause and effect: If I throw this dish, what will happen? Will there be a noise? Will Mom come and give it back to me? How many times will she give it back to me?

Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Stages According to Piaget (1929/1960, 1984), as children develop, their minds constantly adapt to new situations and experiences. Sometimes they assimilate new information into their existing mental categories: A German shepherd and a terrier both fit the category dogs. At other times, however, children must change their mental categories to accommodate their new experiences: A cat does not belong to the category dogs and a new category is required, one for cats. Both processes are constantly interacting, Piaget said, as children go through four stages of cognitive development.

From birth to age 2, said Piaget, babies are in the sensorimotor stage. In this stage, the infant learns through concrete actions: looking, touching, putting things in the mouth, sucking, grasping. “Thinking” consists of coordinating sensory information with bodily movements. Gradually, these movements become more purposeful as the child explores the environment and learns that specific movements will produce specific results. Pulling a cloth away will reveal a hidden toy; letting go of a fuzzy toy duck will cause it to drop out of reach; banging on the table with a spoon will produce dinner (or Mom, taking the spoon away).

A major accomplishment at this stage, said Piaget, is object permanence, the understanding that something continues to exist even when you can't see it or touch it. In the first few months, infants will look intently at a little toy, but if you hide it behind a piece of paper they will not look behind the paper or make an effort to get the toy. By about 6 months of age, however, infants begin to grasp the idea that the toy exists whether or not they can see it. If a baby of this age drops a toy from her playpen, she will look for it; she also will look under a cloth for a toy that is partially hidden. By 1 year of age, most babies have developed an awareness of the permanence of objects; even if a toy is covered by a cloth, it must be under there. This is when they love to play peekaboo. Object permanence, said Piaget, represents the beginning of the child's capacity to use mental imagery and symbols. The child becomes able to hold a concept in mind, to learn that the word fly represents an annoying, buzzing creature and that Daddy represents a friendly, playful one.

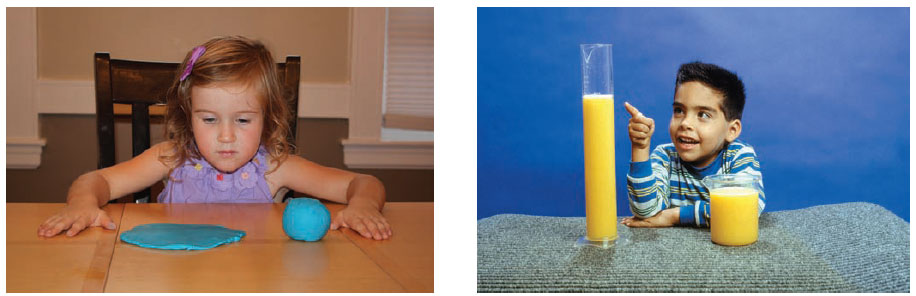

From about ages 2 to 7, the child's use of symbols and language accelerates. Piaget called this the preoperational stage because he believed that children still lack the cognitive abilities necessary for understanding abstract principles. Piaget believed (mistakenly, as we will see) that preoperational children cannot take another person's point of view because their thinking is egocentric: They see the world only from their own frame of reference and cannot imagine that others see things differently. Furthermore, said Piaget, preoperational children cannot grasp the concept of conservation, the notion that physical properties do not change when their form or appearance changes. Children at this age do not understand that an amount of liquid or a number of blocks remains the same even if you pour the liquid from one glass to another of a different size or if you stack the blocks (see Figure13.3). If you pour liquid from a short, fat glass into a tall, narrow glass, preoperational children will say there is more liquid in the second glass. They attend to the appearance of the liquid (its height in the glass) to judge its quantity, and so they are misled.

Figure 13.3

Piagets Principle of Conservation

If you've got access to young children (through babysitting; as an aunt, uncle, or sibling; through a local daycare center; or as a parent yourself), you can examine some of Piagets principles yourself. In one test for conservation of size (left), the child must say which is bigger—a round lump of clay or the same amount of clay pressed flat. Preoperational children think that the flattened clay is bigger because it seems to take up more space. In a test for conservation of quantity (right), the child is shown two short glasses with equal amounts of liquid. Then the contents of one glass are poured into a tall, narrower glass, and the child is asked whether one container now has more. Most preoperational children do not understand that pouring liquid from a short glass into a taller one leaves the amount of liquid unchanged. They judge only by the height of liquid in the glass.

From the ages of 7 to about 12, Piaget said, children increasingly become able to take other people's perspectives and they make fewer logical errors. Piaget called this the concrete operations stage because he thought children's mental abilities are tied to information that is concrete, that is, to actual experiences that have happened or concepts that have a tangible meaning to them. Children at this stage make errors of reasoning when they are asked to think about abstract ideas such as “patriotism” or “future education.” During these years, nonetheless, children's cognitive abilities expand rapidly. They come to understand the principles of conservation and of cause and effect. They learn mental operations, such as basic arithmetic. They are able to categorize things (e.g., oaks as trees) and to order things serially from smallest to largest, lightest to darkest, and shortest to tallest.

Finally, said Piaget, beginning at about age 12 or 13 and continuing into adulthood, people become capable of abstract reasoning and enter the formal operations stage. They are able to reason about situations they have not experienced firsthand, and they can think about future possibilities. They are able to search systematically for answers to problems. They are able to draw logical conclusions from premises common to their culture and experience.

Current Views of Cognitive Development Piaget's central idea has been well supported: New reasoning abilities depend on the emergence of previous ones. You cannot learn algebra before you can count, and you cannot learn philosophy before you understand logic. But since Piaget's original work, the field of developmental psychology has undergone an explosion of imaginative research that has allowed investigators to get into the minds of even the youngest infants. The result has been a modification of Piaget's ideas, and some developmental scientists go so far as to say that his ideas have been overturned. Here's why:

Cognitive abilities develop in continuous, overlapping waves rather than discrete steps or stages. If you observe children at different ages, as Piaget did, it will seem that they reason differently. But if you study the everyday learning of children at any given age, you will find that a child may use several different strategies to solve a problem, some more complex or accurate than others (Siegler, 2006). Learning occurs gradually, with retreats to former ways of thinking as well as advances to new ones. Children's reasoning ability also depends on the circumstances—who is asking them questions, the specific words used, the materials used, and what they are reasoning about—and not just on the stage they are in. In short, cognitive development is continuous; new abilities do not simply pop up when a child turns a certain age (Courage & Howe, 2002).

Preschoolers are not as egocentric as Piaget thought. Most 3- and 4-year-olds can take another person's perspective (Flavell, 1999). When 4-year-olds play with 2-year-olds, they modify and simplify their speech so the younger children will understand (Shatz & Gelman, 1973). One preschooler we know showed her teacher a picture she had drawn of a cat and an unidentifiable blob. “The cat is lovely,” said the teacher, “but what is this thing here?” “That has nothing to do with you,” said the child. “That's what the cat is looking at.”

By about ages 3 to 4, children also begin to understand that you cannot predict what a person will do just by observing a situation or knowing the facts. You also have to know what the person is feeling and thinking; the person might be mistaken or even be lying. They start asking why other people behave as they do (“Why is Johnny so mean?”). In short, they are developing a theory of mind, a system of beliefs about how their own and other people's minds work and how people are affected by their beliefs and emotions. They begin to use verbs like think and know, and by age 4, they understand that what another person thinks might not match their own knowledge. In one typical experiment, a child watched as another child placed a ball in the closet and left the room. An adult then entered and moved the ball into a basket. Three-year-olds predicted that when the other child returned, he would look for the ball in the basket because that is where the 3-year-old knew it was. But 4-year-olds said that the child would look in the closet, where the other child believed it was (Flavell, 1999; Wellman, Cross, & Watson, 2001).

Remarkably, early aspects of a theory of mind are present in infancy: Babies aged 13 to 15 months are surprised when they realize that an adult has a false or pretend belief (Luo & Baillargeon, 2010). The ability to understand that people can have false beliefs is a milestone because it means the child is beginning to question how we know things—the foundation for later higher-order thinking (Moll, Kane, & McGowan, 2015).

Children, even infants, reveal cognitive abilities much earlier than Piaget believed possible. Taking advantage of the fact that infants look longer at novel or surprising stimuli than at familiar ones, psychologists have designed delightfully innovative methods of testing what babies know. These methods reveal that babies may be born with mental modules or core knowledge systems for numbers, spatial relations, the properties of objects, and other features of the physical world (Kibbe & Leslie, 2011; Schultz & Tomasello, 2015; Scott & Baillargeon, 2013; Spelke & Kinzler, 2007.

Thus, at only 4 months of age, babies will look longer at a ball if it seems to roll through a solid barrier, leap between two platforms, or hang in midair than they do when the ball obeys the laws of physics. This suggests that the unusual event is surprising to them (see Figure13.4). Infants as young as 2½ to 3½ months are aware that objects continue to exist even when masked by other objects, a form of object permanence that Piaget never imagined possible in babies so young (Baillargeon, 2004). And, most devastating to Piaget's notion of infant egocentrism, even 5-month-old infants are able to perceive other people's actions as being intentional; they detect the difference between a person who is reaching for a toy with her hand rather than accidentally touching it with a stick (Woodward, 2009). Even 3-month-old infants can learn this. At that tender age, they are obviously not yet skilled at intentionally reaching for objects. But when experimenters covered their little hands with “sticky mittens”—covered with Velcro—so that soft toys would stick to them, the babies actually learned from that experience to distinguish the intentional versus accidental reaches of others (Sommerville, Woodward, & Needham, 2005).

Figure 13.4

Testing Infants' Knowledge

Cognitive development is influenced by a child's culture. One of Piaget's contemporaries, Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934), had disagreed with Piaget by emphasizing the sociocultural influences on children's cognitive development. Vygotsky (1962) believed that children develop mental representations of the world through culture, language, and the environment, and that adults play a major role in this process by constantly guiding and teaching their children. As a result, he said, instead of going through invariant stages, a child's cognitive development may proceed in any number of directions. Vygotsky was correct. Culture—the world of tools, language, rituals, beliefs, games, and social institutions—shapes and structures children's cognitive development, fostering some abilities and not others (Tomasello, 2014). Thus, nomadic hunters excel in spatial abilities because spatial orientation is crucial for finding water holes and successful hunting routes. In contrast, children who live in settled agricultural communities, such as the Baoulé of the Ivory Coast, develop rapidly in the ability to quantify but much more slowly in spatial reasoning.

Despite these modifications, Piaget left an enduring legacy: the insight that children are not passive vessels into which education and experience are poured. Children actively interpret their worlds, using their developing abilities to assimilate new information and figure things out. As the video How Thinking Develops points out, these insights have shaped psychologists’ own thinking about thinking.

Experience and culture influence cognitive development. Children who work with clay, wood, and other materials, such as this young potter in India, tend to understand the concept of conservation sooner than children who have not had this kind of experience.

Watch

How Thinking Develops