13.4

Gender Development

When they learned a baby girl was on the way, our two psychologist friends took a scientific approach to naming her. First they consulted lists of the 100 most popular names over the past several years and selected those between 51 and 100; popular, but not too popular. Then they chose names that were gender-neutral, such as Chris or Morgan, and asked a sample of friends to rate both the familiarity and femininity of a large set of names. When the data were analyzed (and the parents weighed in with their own preferences), their daughter Casey finally had her name.

But then something curious happened. Casey was born without a lot of hair, and her parents shied away from early ear-piercing, ribbons and bows, or garish pink clothing. Within the first year of her life, strangers would comment “What a darling little fellow!” or “Hi there, champ,” assuming that this child, devoid of many typical gender markers, must be a boy. The efforts to give Casey a fair start in life, with a gender-neutral name that wouldn't immediately activate people's stereotypical assumptions about girls, didn't stop people from defaulting to a different stereotype: Males are normative, and females are the exception (Gilman, 1911).

Psychological scientists have increasingly turned their attention to understanding what it means to be a “girl” or a “boy,” “female” or “male,” and all that is bound up in those time-honored yet currently shifting conceptions of how to categorize people in the world. In terms of gender development, some of the primary questions are these: How soon do children notice that girls and boys are different sexes and understand which sex they themselves are? How do children learn the rules of femininity and masculinity, the things that girls do that are different from what boys do?

Gender Identity

Let's start by clarifying some terms. Gender identity refers to a child's sense of being male or female, of belonging to one sex and not the other. Gender typing is the process of socializing children into their gender roles, and thus reflects society's ideas about which abilities, interests, traits, and behaviors are appropriately masculine or feminine. A person can have a strong gender identity and not be gender typed: A man may be confident in his maleness and not feel threatened by doing “unmasculine” things such as needlepointing a pillow; a woman may be confident in her femaleness and not feel threatened by doing “unfeminine” things such as serving in combat. The factors that influence sex and gender are discussed in the video Sex and Gender Differences 2.

Watch

Sex and Gender Differences 2

In the past, psychologists tried to distinguish the terms sex and gender, reserving “sex” for the physiological or anatomical attributes of males and females and “gender” for differences that are learned. Thus, they might speak of a sex difference in the frequency of baldness but a gender difference in fondness for romance novels. Today, these two terms are often used interchangeably because, as we have noted repeatedly in this book, nature and nurture are inextricably linked (Roughgarden, 2004).

The complexity of sex and gender development is especially apparent in people who do not fit the familiar categories of male and female. Every year, thousands of babies are born with intersex conditions, formerly known as hermaphroditism. In these conditions, chromosomal or hormonal anomalies cause the child to be born with ambiguous genitals, or genitals that conflict with the infant's chromosomes. A child who is genetically female might be born with an enlarged clitoris that looks like a penis. A child who is genetically male might be born with androgen insensitivity, a condition that causes the external genitals to appear female.

As adults, many intersexed individuals call themselves transgender, a term describing a broad category of people who do not fit comfortably into the usual categories of male and female, masculine and feminine. Some transgender people are comfortable living with the physical attributes of both sexes, considering themselves to be “gender queer” and even refusing to be referred to as he or she. Some feel uncomfortable in their sex of rearing and wish to be considered a member of the other sex. You have probably also heard the term transsexual, describing people who are not intersexed yet who feel that they are male in a female body or vice versa; their gender identity is at odds with their anatomical sex or appearance. Many transsexuals try to make a full transition to the other sex through surgery or hormones. Intersexed people and transsexuals have lived in virtually all cultures throughout history (Denny, 1998; Roughgarden, 2004). Recently, Facebook acknowledged the diversity of people's conceptions of their gender identity by offering over 50 possibilities for gender identification, such as gender fluid, nonbinary, two-spirit, or cisgender (Ball, 2014).

What Is "Gender"?

Influences on Gender Development

To understand the typical course of gender development, as well as the variations, developmental psychologists study the interacting influences of biology, cognition, and learning on gender identity and gender typing.

Biological Influences Starting in the preschool years, boys and girls congregate primarily with other children of their sex, and most prefer the toys and games of their own sex. They will play together if required to, but given their druthers, they usually choose to play with same-sex friends. The kind of play that young girls and boys enjoy also differs, on average. Little boys, like young males in all primate species, are more likely than females to go in for physical roughhousing, risk taking, and aggressive displays. These sex differences occur all over the world, almost regardless of whether adults encourage boys and girls to play together or separate them (Lytton & Romney, 1991; Maccoby, 1998, 2002). Many parents lament that although they try to give their children the same toys, it makes no difference; their sons want trucks and guns and their daughters want dolls.

Biological scientists believe that these play and toy preferences have a basis in prenatal hormones, particularly the presence or absence of prenatal androgens (masculinizing hormones). Girls who were exposed to higher-than-normal prenatal androgens in the womb are later more likely than nonexposed girls to prefer “boys' toys” such as cars and fire engines, and they are also more physically aggressive than other girls (Berenbaum & Bailey, 2003; Martin & Dinella, 2012). A study of more than 200 healthy children in the general population also found a relationship between fetal testosterone and play styles. (Testosterone is produced in fetuses of both sexes, although it is higher on average in males.) The higher the levels of fetal testosterone, as measured in the amniotic fluid of the children's mothers during pregnancy, the higher the children's later scores on a measure of male-typical play (Auyeung et al., 2009). In studies of rhesus monkeys, who of course are not influenced by their parents' possible gender biases, male monkeys, like human boys, consistently and strongly prefer to play with wheeled toys rather than cuddly plush toys, whereas female monkeys, like human girls, are more varied in their toy preferences (Hassett, Siebert, & Wallen, 2008).

Do these findings have anything to do with gender identity, the core sense of being female or male? A psychologist reviewed hundreds of cases of children whose sex of rearing was discrepant with their anatomical or genetic sex. He learned that the answer is enormously complex because a person's gender identity depends on the interactions of genes, prenatal hormones, anatomical structures, and experiences in life (Zucker, 1999). Consider a longitudinal study of 16 genetic males who had a rare condition that caused them to be born without a penis. The babies were otherwise normal males, with testicles and appropriate androgen levels. Two of the boys were raised as male and developed a male gender identity. Fourteen had been socially and surgically assigned to the female sex, according to the custom when they were born. Of those 14, eight eventually declared themselves male, five decided to live as females, and one had an unclear gender identity (Reiner & Gearheart, 2004).

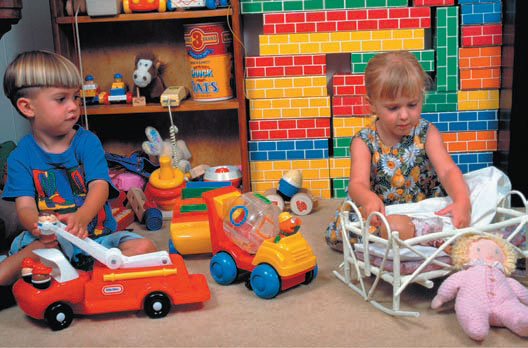

Look familiar? In a scene typical of many homes and nursery schools, the boy likes to play with trucks and the girl with dolls. Whether or not such behavior is biologically based, the gender rigidity of the early years does not inevitably continue into adulthood unless cultural rules reinforce it.

Cognitive Influences Cognitive psychologists explain the mystery of children's gender segregation and toy and play preferences by studying children's changing cognitive abilities. Even before babies can speak, they can discriminate two sexes. By the age of 9 months, most babies can discriminate female from male faces (Fagot & Leinbach, 1993), and they can match female faces with female voices (Poulin-Dubois et al., 1994). By the age of 18 to 20 months, most toddlers have a concept of gender labels. They can accurately identify their own gender and that of people in picture books and begin correctly using the words boy, girl, and man (interestingly, lady and woman come later) (Zosuls et al., 2009).

After children can label themselves and others consistently as being a boy or a girl, shortly before age 2, they change their behavior to conform to the category they belong to. Many begin to prefer same-sex playmates and sex-traditional toys without being explicitly taught to do so (Halim et al., 2014; Martin, Ruble, & Szkrybalo, 2002). They become more gender typed in their toy play, games, aggressiveness, and verbal skills than children who still cannot consistently label males and females. Most notably, girls stop behaving aggressively (Fagot, 1993). It is as if they go along behaving like boys until they know they are girls. At that moment, they seem to decide: “Girls don't do this. I'm a girl; I'd better not either.”

By about age 5, most children have developed a stable gender identity, a sense of themselves as being male or female regardless of what they wear or how they behave. Only then do they understand that what girls and boys do does not necessarily indicate what sex they are: A girl remains a girl even if she can climb a tree, and a boy remains a boy even if he has long hair. At this age, children consolidate their knowledge, with all of its mistakes and misconceptions, into a gender schema, a mental network of beliefs and expectations about what it means to be male or female and about what each sex is supposed to wear, do, feel, and think (Bem, 1993; Martin & Ruble, 2004). Gender schemas are most rigid between ages 5 and 7; at this age, it's really hard to dislodge a child's notion of what boys and girls can do (Martin et al., 2002).

Gender schemas even include metaphors. After age 4, children of both sexes will usually say that rough, spiky, black, or mechanical things are male and that soft, pink, fuzzy, or flowery things are female; that black bears are male and pink poodles are female (Leinbach, Hort, & Fagot, 1997; Swinkels, 2009). But the content of these schemas is not innate. A hundred years ago, an article in Ladies' Home Journal advised: “The generally accepted rule is pink for the boys, and blue for the girls. The reason is that pink, being a more decided and stronger color, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl” (Paoletti, 2012). The invention of gender-specific “rules” of clothing for babies and young children was a creation of late 20th-century marketing.

Many people retain inflexible gender schemas throughout their lives. They feel uncomfortable or angry with men or women who break out of traditional roles, not to mention with transgendered individuals who don't fit either category or want to change the one they grew up with. However, with experience and cognitive sophistication, older children often become more flexible in their gender schemas, especially if they have friends of the other sex and if their families and cultures encourage such flexibility (Martin & Ruble, 2004).

Cultures and religions, too, differ in their schemas for the roles of women and men. In all Western, industrialized nations, it is taken for granted that women and men alike should be educated; indeed, laws mandate a minimum education for both sexes. But in cultures where female education is prohibited in the name of religious law, many girls who attend school receive death threats and some have had acid thrown on their faces. Gender schemas can be powerful, and events that challenge their legitimacy can be enormously threatening.

Learning Influences A third influence on gender development is the environment, which is full of subtle and not-so-subtle messages about what girls and boys are supposed to do. Behavioral and social-cognitive learning theorists study how the process of gender socialization instills these messages in children (Bussey & Bandura, 1999). They find that gender socialization begins at the moment of birth. Many parents are careful to dress their baby in outfits they consider to be the correct color and pattern for his or her sex. Clothes don't matter to the infant, of course, but they are signals to adults about how to treat the child; remember the case of Casey, whom you read about earlier? Adults often respond to the same baby differently, depending on whether the child is dressed as a boy or a girl (Shakin, Shakin, & Sternglanz, 1985).

Parents, teachers, and other adults convey their beliefs and expectations about gender even when they are entirely unaware that they are doing so. When parents believe that boys are naturally better at math or sports and that girls are naturally better at English, they unwittingly communicate those beliefs by how they respond to a child's success or failure. They may tell a son who did well in math, “You're a natural math whiz, Johnny!” But if a daughter gets good grades, they may say, “Wow, you really worked hard in math, Joanie, and it shows!” The implication is that girls have to try hard but boys have a natural gift. Messages like these are not lost on children. Both sexes tend to lose interest in activities that are supposedly not natural for them, even when they all start out with equal abilities (Dweck, 2006; Frome & Eccles, 1998).

In today's fast-moving world, however, society's messages to women and men, and parents' messages to their children, keep evolving. As a result, gender development has become a lifelong process, in which gender schemas, attitudes, and behavior change as people have new experiences and as society itself changes (Rosin, 2012). Five-year-old children may behave like sexist piglets while they are trying to figure out what it means to be male or female. Their behavior is shaped by a combination of hormones, genetics, cognitive schemas, parental and social lessons, religious and cultural customs, and experiences. But their gender-typed behavior as 5-year-olds usually has little to do with how they will behave at 25 or 45. In fact, by early adulthood, women and men show virtually no average differences in cognitive abilities, personality traits, self-esteem, or psychological well-being (Hyde, 2007).

That is why children can grow up in an extremely gender-typed family and yet, as adults, find themselves in careers or relationships or identities they would never have imagined for themselves. If 5-year-olds are the gender police, many adults end up breaking the law.

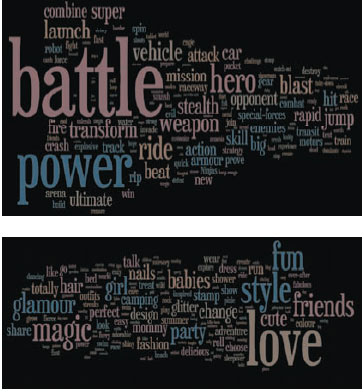

Crystal Smith transcribed a number of commercials directed to “boys” or “girls,” and made these “word clouds” out of the result. You can see at once how advertisers cater to exaggerated gender schemas.