14.3

Genetic Influences on Personality

A mother we know was describing her two children: “My daughter has always been difficult, intense, and testy,” she said, “but my son is the opposite, placid and good-natured. They came out of the womb that way.” Was this mother right? Is it possible to be born touchy or good-natured? What aspects of personality might have an inherited component? Researchers measure genetic contributions to personality in three ways: by studying personality traits in other species, by studying the temperaments of human infants and children, and by conducting heritability studies of twins and adopted individuals. Let's examine each of these approaches in turn.

Heredity and Temperament

LO 14.3.A Define what temperaments are, and discuss how they relate to personality traits.

Listen to the Audio

Let's turn now to human personalities. Even in the first weeks after birth, human babies differ in activity level, mood, responsiveness, heart rate, and attention span (Fox et al., 2005a). Some are irritable and cranky; others are placid and calm. Some will cuddle up in an adult's arms and snuggle; others squirm and fidget, as if they cannot stand being held. Some smile easily; others fuss and cry. These differences appear even when you control for possible prenatal influences, such as the mother's nutrition, drug use, or problems with the pregnancy. Babies thus are born with genetically influenced temperaments, dispositions to respond to the environment in certain ways (Clark & Watson, 2008). Temperaments include reactivity (how excitable, arousable, or responsive a baby is), soothability (how easily the baby is calmed when upset), and positive and negative emotionality. Temperaments are quite stable over time and are the clay out of which later personality traits are molded (Clark & Watson, 2008; Dyson et al., 2015; Else-Quest et al., 2006).

Heredity and Temperament

Even at 4 months of age, highly reactive infants are excitable, nervous, and fearful; they overreact to any little thing, even a colorful picture placed in front of them. As toddlers, they tend to be wary and fearful of new things—toys that make noise, odd-looking robots—even when their moms are right there. At 5 years, many of these children are still timid and uncomfortable in new situations and with new people (Hill-Soderlund & Braungart-Rieker, 2008). At 7 years, many still have symptoms of anxiety, even if nothing traumatic has ever happened to them. They are afraid of being kidnapped, they need to sleep with the light on, and they are afraid of sleeping in an unfamiliar house. In contrast, nonreactive infants lie there without fussing, babbling happily; they rarely cry. As toddlers, they are outgoing and curious about new toys and events. They continue to be easygoing throughout childhood (Fox et al., 2005a; Kagan, 1997).

Children at these two extremes differ physiologically, too. During mildly stressful tasks, reactive children are more likely than nonreactive children to have increased heart rates, heightened brain activity, and high levels of stress hormones. You can see how biologically based temperaments might form the basis of the later personality traits we call extroversion, agreeableness, or neuroticism.

Heredity and Traits

LO 14.3.B Explain how twin studies can be used to estimate the heritability of personality traits.

Listen to the Audio

A third way to study genetic contributions to personality is to estimate the heritability of specific traits within groups of children or adults. Heritability refers to the proportion of the total variation in a trait that is attributable to genetic variation within a group. Estimates of heritability come from behavioral-genetic studies of adopted children and of identical and fraternal twins reared apart and together.

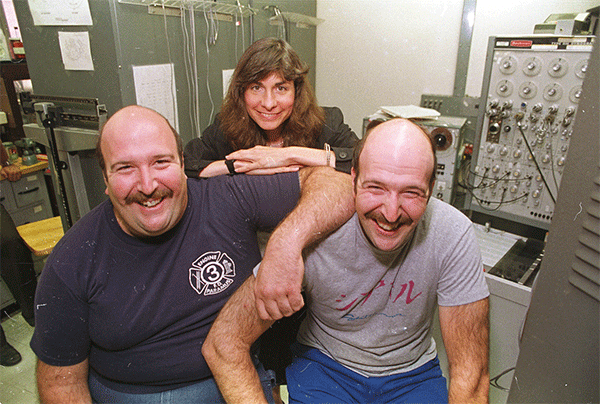

Identical twins Gerald Levey (left) and Mark Newman were separated at birth and raised in different cities. When they were reunited at age 31, they discovered some astounding similarities. Both were volunteer firefighters, wore mustaches, and were unmarried. Both liked to hunt, watch old John Wayne movies, and eat Chinese food. They drank the same brand of beer, held the can with the little finger curled around it, and crushed the can when it was empty. It’s tempting to conclude that all of these similarities are due to heredity, but we should also consider other explanations: Some could result from shared environmental factors such as social class and upbringing, and some could be due merely to chance. For any given set of twins, we can never know for sure.

Findings from adoption and twin studies have provided compelling support for a genetic contribution to personality. Identical twins reared apart will often have unnerving similarities in gestures, mannerisms, and moods; indeed, their personalities often seem as similar as their physical features. If one twin tends to be optimistic, glum, or excitable, the other will probably be that way too (Braungart et al., 1992; Plomin, DeFries, & Knopik, 2013). Behavioral-genetic findings have produced remarkably consistent results: For the Big Five and many other traits from aggressiveness to overall happiness, heritability is about .50 (Bartels, 2015; Bouchard, 1997a; Lykken & Tellegen, 1996; Vukasović & Bratko, 2015; Waller et al., 1990; Weiss, Bates, & Luciano, 2008). This means that within a group of people, about 50 percent of the variation in such traits is attributable to genetic differences among the individuals in the group. These findings have been replicated in many countries. For more information on heritability and personality, watch the video Twins and Personality.

Watch

Twins and Personality

Evaluating Genetic Theories

LO 14.3.C Summarize the arguments for and against the conclusion that personality “is all in our genes.”

Listen to the Audio

Behavioral-genetic research, to date, permits us only to infer the existence of relevant genes—just as, if you find a toddler covered in chocolate, it's pretty safe to infer that candy is somewhere close by. Scientists expect that the actual genes underlying key traits will one day be discovered, and dozens of possible associations between specific genes and personality traits have already been reported (Fox et al., 2005b; Plomin, DeFries, & Knopik, 2013). You will be hearing lots more about genetic discoveries in the coming years, so it is good to understand what they mean and don't mean.

Psychologists hope that one intelligent use of behavioral-genetic findings will be to help people become more accepting of themselves and their children. Although we can all learn to make improvements and modifications to our personalities, most of us probably will never be able to transform our personalities completely because of our genetic dispositions and temperaments. This realization might make people more realistic about what psychotherapy can do for them, and about what they can do for their children.

However, many people oversimplify this information and conclude “it's all in our genes.” A judge in New York imposed a severe sentence on a man convicted of one count of possession of child pornography because the judge was sure the man had “an as-of-yet-undiscovered gene” that caused his behavior. (That judge needs to take an intro psych course.) Fortunately, the ruling was overturned. This judge not only knew nothing about genetics—there is no “porn gene”—but also failed to understand that even when genetics are involved in some behavior, having a genetic predisposition does not necessarily imply genetic inevitability. A person might have a genetic predisposition toward depression or anxiety, but without certain environmental stresses or circumstances, the person will probably not develop an emotional disorder.

As Robert Plomin (1989), a leading behavioral geneticist, observed, “The wave of acceptance of genetic influence on behavior is growing into a tidal wave that threatens to engulf the second message of this research: These same data provide the best available evidence for the importance of environmental influences.” Let us now see what some of those influences might be.