14.4

Environmental Influences on Personality

The environment may exert an influence on variations in personality, but what is the environment, exactly? In this section, we will consider the relative influence of three aspects of the environment: the particular situations you find yourself in, how your parents treat you, and who your peers are.

Situations and Social Learning

The very definition of a trait is that it is consistent across situations. But people often behave one way with their parents and a different way with their friends, one way at home and a different way in other settings. In learning terms, the reason for people's inconsistency is that different behaviors are rewarded, punished, or ignored in different contexts. You are more likely to be extroverted in an audience of screaming, cheering Taylor Swift fans than at home with relatives who would regard such noisy displays with alarm and condemnation. This is why some behaviorists think it does not even make much sense to talk about “personality.”

Social-cognitive learning theorists, however, argue that people do acquire central personality traits from their learning history and their resulting expectations and beliefs.A child who studies hard and gets good grades, attention from teachers, admiration from friends, and praise from parents will come to expect that hard work in other situations will also pay off. That child will become, in terms of personality traits, “ambitious” and “motivated.” A child who studies hard and gets poor grades, is ignored by teachers and parents, and is rejected by friends for being a grind will come to expect that working hard isn't worth it. That child will become, in terms of personality traits, “unambitious” or “unmotivated.”

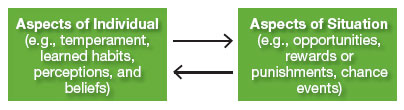

Today, most personality researchers recognize that people can have a core set of stable traits and that their behavior can vary across situations (Fleeson, 2004). Your particular qualities continually interact with the situation you are in. Your temperaments, habits, and beliefs influence how you respond to others, whom you hang out with, and the situations you seek (Bandura, 2001; Cervone & Shoda, 1999; Mischel & Shoda, 1995). In turn, the situation influences your behavior and beliefs, rewarding some and extinguishing others. In social-cognitive learning theory, this process is called reciprocal determinism.

The two-way process of reciprocal determinism (as opposed to the one-way determinism of “genes determine everything” or “everything is learned”) helps answer a question asked by everyone who has a sibling: What makes children who grow up in the same family so different, apart from their genes? The answer seems to be: an assortment of experiences that affect each child differently, chance events that cannot be predicted, situations that children find themselves in, and peer groups that the children belong to (Harris, 2006; Plomin, 2011; Rutter et al., 2001). Behavioral geneticists refer to these unique and chance experiences that are not shared with other family members as the nonshared environment: being in Mrs. Schmidt's class in the fourth grade (which might inspire you to become a scientist), winning the lead in the school play (which might push you toward an acting career), or being bullied at school (which might have caused you to see yourself as weak and powerless). All of these experiences work reciprocally with your own interpretation of them, your temperament, and your perceptions (Did Mrs. Schmidt's class excite you or bore you?).

Keeping the concept of reciprocal determinism in mind, let us look at two of the most important environmental influences in people's lives: their parents and their friends.

Who is the “real” Beyoncé—doting mother or Sasha Fierce, the persona she used to put on in each performance? By understanding reciprocal determinism, we can avoid oversimplifying. Our genetic dispositions and personality traits cause us to choose some situations over others, but situations then influence which aspects of our personalities we express.

Parental Influence—and Its Limits

If you check out parenting books online or in a bookstore, you will find that in spite of the zillion different kinds of advice they offer, they share one entrenched belief: Parental childrearing practices are the strongest influence, maybe even the sole influence, on children's personality development. For many decades, few psychologists thought to question this assumption, and many still accept it. Yet the belief that personality is primarily determined by how parents treat their children has begun to crumble under the weight of three kinds of evidence (Harris, 2006, 2009; Plomin, 2011):

The shared environment of the home has relatively little influence on most personality traits. In behavioral-genetic research, the “shared environment” includes the family you grew up with and the experiences and background you shared with your siblings and parents. If these had as strong an influence as commonly assumed, then studies should find a strong correlation between the personality traits of adopted children and those of their adoptive parents. In fact, the correlation is weak to nonexistent, indicating that the influence of childrearing practices and family life is very small compared to the influence of genetics (Cohen, 1999; Plomin, 2011). It is only the nonshared environment that has a strong impact.

Few parents have a single childrearing style that is consistent over time and that they use with all their children. Developmental psychologists have tried for many years to identify the effects of specific childrearing practices on children's personality traits. The problem is that parents are inconsistent from day to day and over the years. Their childrearing practices vary, depending on their own stresses, moods, and marital satisfaction (Holden & Miller, 1999). As one child we know said to her exasperated mother, “Why are you so mean to me today, Mommy? I'm this naughty every day.” Moreover, parents tend to adjust their methods of childrearing according to the temperament of the child; they are often more lenient with easygoing children and more punitive with difficult ones.

Even when parents try to be consistent in the way they treat their children, there may be little relation between what they do and how the children turn out. Some children of troubled and abusive parents are resilient and do not suffer lasting emotional damage, and some children of the kindest and most nurturing parents succumb to drugs, mental illness, or gangs.

Of course, parents do influence their children in lots of ways that are unrelated to the child's personality. They contribute to their children's religious beliefs, intellectual and occupational interests, motivation to succeed, skills, values, and adherence to traditional or modern notions of masculinity and femininity (Beer, Arnold, & Loehlin, 1998; Krueger, Hicks, & McGue, 2001). Above all, what parents do profoundly affects the quality of their relationship with their children—whether their children feel loved, secure, and valued or humiliated, frightened, and worthless (Harris, 2009).

Parents also have some influence even on traits in their children that are highly heritable. In one longitudinal study that followed children from age 3 to age 21, those who were impulsive, uncontrollable, and aggressive at age 3 were far more likely than calmer children to grow up to be impulsive, unreliable, and antisocial and more likely to commit crimes (Caspi, 2000). Early temperament was a strong and consistent predictor of these later personality traits. But not every child came out the same way. What protected some of those at risk, and helped them move in a healthier direction, was having parents who made sure they stayed in school, supervised them closely, and gave them consistent discipline.

Nevertheless, it is clear that, in general, parents have less influence on a child's personality than many people think. Because of reciprocal determinism, the relationship runs in both directions, with parents and children continually influencing one another. Moreover, as soon as children leave home, starting in preschool, parental influence on children's behavior outside the home begins to wane. The nonshared environment—peers, chance events, and circumstances—takes over.

[[For Revel: Insert Interactive 14.6.]]

What Has Shaped Your Personality?

The Power of Peers

When two psychologists surveyed 275 freshmen at Cornell University, they found that most of them had secret lives and private selves that they never revealed to their parents (Garbarino & Bedard, 2001). On Facebook, many teenagers report having committed crimes, drinking, taking drugs, cheating in school, sexting, and having sex, all without their parents having a clue. (They assume, often incorrectly, that what they reveal is private and read only by their several hundred closest friends.) This phenomenon of showing only one facet of your personality to your parents and an entirely different one to your peers becomes especially apparent in adolescence.

Children, like adults, live in two environments: their homes and their world outside the home. At home, children learn how their parents want them to behave and what they can get away with; as soon as they go to school, however, they conform to the dress, habits, language, and rules of their peers. Most adults can remember how terrible they felt when their classmates laughed at them for pronouncing a word “the wrong way” or doing something “stupid” (i.e., not what the rest of the kids were doing), and many recall the pain of being excluded. To avoid being laughed at or rejected, most children will do what they can to conform to the norms and rules of their immediate peer group (Harris, 2009). Children who were law-abiding in the fifth grade may start breaking the law in high school, if that is what it takes—or what they think it takes—to win the respect of their peers.

It has been difficult to tease apart the effects of parents and peers because parents usually try to arrange things so that their children's environments duplicate their own values and customs. To see which has the stronger influence on personality and behavior, therefore, we must look at situations in which the peer group's values clash with the parents' values. When parents value academic achievement and their child's peers think that success in school is only for sellouts or geeks, whose view wins? The answer, typically, is peers (Arroyo & Zigler, 1995; Harris, 2009; Menting et al., 2015). Conversely, children whose parents gave them no encouragement or motivation to succeed may find themselves with peers who are working like mad to get into college, and start studying hard themselves.

Thus, peers play a tremendous role in shaping our personality traits and behavior, causing us to emphasize some attributes or abilities and downplay others. Of course, as the theory of reciprocal determinism would predict, our temperaments and dispositions also cause us to select particular peer groups (if they are available) instead of others, and our temperaments influence how we behave within the group. But when we are among peers, most of us go along with them, molding facets of our personalities to the pressures of the group.

In sum, core personality traits may stem from genetic dispositions, but they are profoundly shaped by learning, peers, situations, experience, and, as we will see next, the largest environment of all: the culture.