14.5

Cultural Influences on Personality

If you get an invitation to come to a party at 7:00 p.m., what time are you actually likely to get there? If someone gives you the finger or calls you a rude name, are you more likely to become furious or laugh it off? Most Western psychologists regard conscientiousness about time and quickness to anger as personality traits that result partly from genetic dispositions and partly from experience. But culture also has a profound effect on people's behavior, attitudes, beliefs, and the traits they value or disdain.

Individualistic Americans exercise by biking, walking, or jogging, going in different directions and wearing different clothes while they do it. Collectivist Japanese employees at their hiring ceremony exercise in identical fashion.

Culture, Values, and Traits

Quick! Answer this question: “Who are you?”

Your answer will be influenced by your cultural background, and particularly by whether your culture emphasizes individualism or community (Hofstede & Bond, 1988; Kanagawa, Cross, & Markus, 2001; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Triandis, 1996, 2007). In individualist cultures, the independence of the individual often takes precedence over the needs of the group, and the self is often defined as a collection of personality traits (“I am outgoing, agreeable, and ambitious”) or in occupational terms (“I am a psychologist”). In collectivist cultures, group harmony often takes precedence over the wishes of the individual, and the self is defined in the context of relationships and the community (“I am the son of a farmer, descended from three generations of storytellers on my mother's side and five generations of farmers on my father's side . . .”) (see Table14.1). In one fascinating study that showed how embedded this dimension is in language and how it shapes our thinking, bicultural individuals born in China tended to answer “Who am I?” in terms of their own individual attributes when they were writing in English. But they described themselves in terms of their relations to others when they were writing in Chinese (Ross, Xun, & Wilson, 2002).

Table 14.1

Some Average Differences between Individualist and Collectivist Cultures

| Members of Individualist Cultures | Members of Collectivist Cultures |

|---|---|

| Define the self as autonomous, independent of groups. | Define the self as an interdependent part of groups. |

| Give priority to individual, personal goals. | Give priority to the needs and goals of the group. |

| Value independence, leadership, achievement, self-fulfillment. | Value group harmony, duty, obligation, security. |

| Give more weight to an individual's attitudes and preferences than to group norms as explanations of behavior. | Give more weight to group norms than to individual attitudes as explanations of behavior. |

| Attend to the benefits and costs of relationships; if costs exceed advantages, a person is likely to drop the relationship. | Attend to the needs of group members; if a relationship is beneficial to the group but costly to the individual, the individual is likely to stay in the relationship. |

Source:Triandis (1996).

Culture and the Self Individualist and collectivist ways of defining the self influence many aspects of life, including which personality traits we value, how and whether we express emotions, how much we value having relationships or maintaining freedom, and how freely we express angry or aggressive feelings (Forbes et al., 2009; Oyserman & Lee, 2008; Yamawaki, Spackman, & Parrott, 2015). These influences are subtle but powerful. In one study, Chinese and American pairs had to play a communication game that required each partner to be able to take the other's perspective. Eye-gaze measures showed that the Chinese players were almost always able to look at the target from their partner's perspective, whereas the American players often completely failed at this task (Wu & Keysar, 2007). Of course, members of both cultures understand the difference between their own view of things and that of another person's, but the collectivist-oriented Chinese pay closer attention to other people's nonverbal expressions, the better to monitor and modify their own responses.

Because people from collectivist cultures are concerned with adjusting their own behavior depending on the social context, they tend to regard personality and the sense of self as being more flexible than people from individualist cultures do. In a study comparing Japanese and Americans, the Americans reported that their sense of self changes only 5 to 10 percent in different situations, whereas the Japanese said that 90 to 99 percent of their sense of self changes (de Rivera, 1989). The group-oriented Japanese believe it is important to enact tachiba, to perform your social roles correctly so that there will be harmony with others. Americans, in contrast, tend to value “being true to your self” and having a “core identity.” Americans often value “self”-enhancement even at the expense of others, but the Japanese way of being a “good self” is through constant self-criticism in the context of maintaining face with others (Hamamura & Heine, 2008).

To further separate universal from culture-specific aspects of personality, a group of cross-cultural psychologists conducted in-depth research with Chinese (in Hong Kong and mainland China) and South Africans, administering Western personality inventories but also developing indigenous measures to capture cultural variations (Cheung, van de Vijver, & Leong, 2011). In China, they found evidence for a personality factor they call “interpersonal relatedness.” This trait occurs universally, just as the Big Five do, but Asians, and Asian Americans who are less acculturated to American society, score higher on it than do European Americans or highly acculturated Asian Americans. In South Africa, where a personality inventory has been developed in the nine official Bantu languages, Afrikaans, and English, the researchers found the familiar Big Five, but also a few other central factors, including “relationship harmony” (approachability vs. distance, conflict seeking vs. resolving, etc.), “soft-heartedness,” and “facilitating” (providing guidance to others).

Culture and Traits When people fail to understand the influence of culture on behavior, they often attribute another person's mysterious or annoying actions to individual personality traits when they are really due to cultural norms. Take cleanliness. How often do you bathe? Once a day, once a week? Do you regard baths as healthy and invigorating or as a disgusting wallow in dirty water? How often, and where, do you wash your hands—or feet? A person who would seem obsessively clean in one culture might seem an appalling slob in another (Fernea & Fernea, 1994).

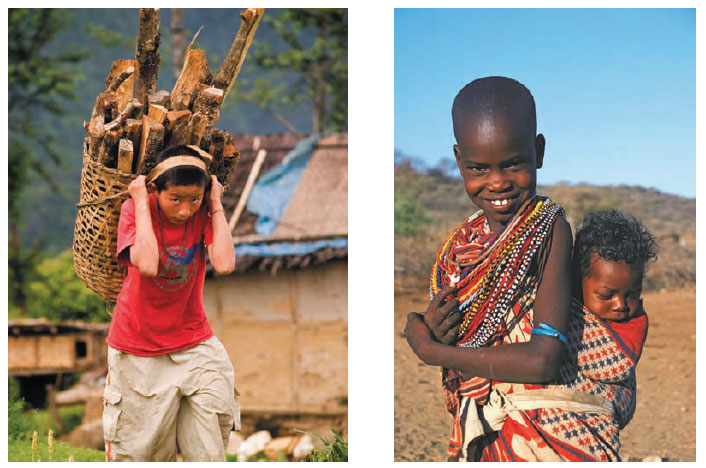

Or consider helpfulness. Many years ago, in a classic cross-cultural study of children in Kenya, India, Mexico, the Philippines, Okinawa, the United States, and five other societies, researchers measured how often children behaved altruistically (offering help, support, or unselfish suggestions) or egoistically (seeking help and attention or wanting to dominate others) (Whiting & Edwards, 1988; Whiting & Whiting, 1975). American children were the least altruistic on all measures and the most egoistic. The most altruistic children came from societies in which children are assigned many tasks, such as caring for younger children and gathering and preparing food. These children knew that their work made a genuine contribution to the well-being or economic survival of the family. In cultures that value individual achievement and self-advancement, taking care of others has less importance, and altruism as a personality trait is not cultivated to the same extent (de Guzman, Do, & Kok, 2014).

Or consider tardiness. Individuals differ in whether they try to be places “on time” or are always late, but cultural norms affect how individuals regard time in the first place. In northern Europe, Canada, the United States, and most other individualistic cultures, time is organized into linear segments in which people do one thing “at a time” (Hall, 1983; Hall & Hall, 1990; Leonard, 2008). The day is divided into appointments, schedules, and routines, and because time is a precious commodity, people don't like to “waste” time or “spend” too much time on any one activity. In such cultures, being on time is taken as a sign of conscientiousness or thoughtfulness and being late as a sign of indifference or intentional disrespect. Therefore, it is considered the height of rudeness (or high status) to keep someone waiting. But in Mexico, southern Europe, the Middle East, South America, and Africa, time is organized along parallel lines. People do many things at once, and the needs of friends and family supersede mere appointments; they think nothing of waiting for hours or days to see someone. The idea of having to be somewhere “on time,” as if time mattered more than a person, is unthinkable.

In many cultures, children are expected to contribute to the family income and to take care of their younger siblings. These experiences encourage helpfulness over independence.

Figure 14.2

Aggression and the Culture of Honor

As these two graphs show, when young men from Northern states were insulted in an experiment, they shrugged it off, thinking it was funny or trivial. But for young Southern men, levels of the stress hormone cortisol and of testosterone shot up, and they were more likely to retaliate aggressively (Cohen et al., 1996).

Evaluating Cultural Approaches

LO 14.5.B Evaluate some pros and cons of the cultural approach to understanding personality.

Listen to the Audio

A woman we know, originally from England, married a Lebanese man. They were happy together but had the usual number of marital misunderstandings and squabbles. After a few years, they visited his family home in Lebanon, where she had never been before. “I was stunned,” she told us. “All the things I thought he did because of his personality turned out to be because he's Lebanese! Everyone there was just like him!”

Our friend's reaction illustrates both the contributions and the limitations of cultural studies of personality. She was right in recognizing that some of her husband's behavior was attributable to his culture; his Lebanese notions of time were indeed very different from her English notions. But she was wrong to infer that the Lebanese are all “like him”: Individuals are affected by their culture, but they vary within it.

Cultural psychologists face the problem of how to describe cultural influences on personality without oversimplifying or stereotyping (Church & Lonner, 1998). As one student of ours put it, “How come when we students speak of ‘the’ Japanese or ‘the’ blacks or ‘the’ whites or ‘the’ Latinos, it's called stereotyping, and when you do it, it's called ‘cross-cultural psychology’?” This question shows excellent critical thinking! The study of culture does not rest on the assumption that all members of a culture behave the same way or have the same personality traits. People vary according to their temperaments, beliefs, and learning histories, and this variation occurs within every culture.

Moreover, culture itself may have variations within every society. The United States has an individualist culture overall, but the South, with its history of strong regional identity, is more collectivist than the rugged, independent West (Vandello & Cohen, 1999). The collectivist Chinese and the Japanese both value group harmony, but the Chinese are more likely to also promote individual achievement, whereas the Japanese are more likely to strive for group consensus (Dien, 1999; Lu, 2008). And African Americans are more likely than white Americans to blend elements of American individualism and African collectivism. Thus, an individualist philosophy predicts grade point average for white students, but collectivist values are a better predictor for black students (Komarraju & Cokley, 2008). Average cross-cultural differences, even in a dimension as influential as individualist–collectivist, are not rigidly fixed or applicable to all groups within a society (Oyserman & Lee, 2008).

Finally, in spite of their differences, cultures share many human concerns and needs for love, attachment, family, work, and religious or communal tradition. Nonetheless, cultural rules are what, on average, make Swedes different from Bedouins, and Cambodians different from Italians. The traits that we value, our sense of self versus community, and our notions of the right way to behave—all key aspects of personality—begin with the culture in which we are raised. And our self-esteem and well-being are deeply influenced by feeling that our own personal traits match the cultural norm: Extroverts are happiest in a culture that values individual success and self-promotion; conscientious people are happiest in a tidy, rule-governed country such as Switzerland. When an individual's personality traits clash with those endorsed by the larger culture, as travelers and immigrants know, people can feel oddly out of sync with the world around them (Fulmer et al., 2010).