15.1

Diagnosing Mental Disorders

Many people confuse unusual behavior—behavior that deviates from the norm—with mental disorder, but the two are not the same. A person may behave in ways that are statistically rare (collecting ceramic dolphins, being a genius at math, committing murder) without having a mental illness. Conversely, some mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety, are extremely common. People also confuse mental disorder and insanity. In the law, the definition of insanity rests primarily on whether a person is aware of the consequences of his or her actions and can control his or her behavior. But insanity is a legal term only; a person may have a mental illness and yet be considered sane by the court.

Dilemmas of Definition

If frequency of the problem is not a guide, and if insanity reflects only one extreme kind of mental illness, how then should we define a “mental disorder”? Diagnosing mental problems is not as straightforward as diagnosing medical problems such as diabetes or appendicitis. One leading definition, which takes evolutionary factors and social values into account, is that a mental disorder is a “harmful dysfunction.” That is, it involves behavior or an emotional state that is (1) harmful to oneself or others, as judged by the community or culture in which it occurs, and (2) dysfunctional because it is not performing its evolutionary function (Wakefield, 2006, 2011). Evolution has prepared us to feel afraid when we are in danger, so that we can escape; dysfunction occurs when this normal alarm mechanism fails to turn off after the danger is past. If the behavior is not troubling to the individual or harmful to society, it is not a mental disorder. Conversely, if the behavior is harmful or undesirable, such as illiteracy and delinquency, it is still not necessarily a mental disorder if an evolutionary function isn't involved.

Self-Expression...or Mental Disorder?

[[For Revel: Insert Interactive 15.2]]

This definition rules out behavior that simply departs from current social or cultural notions of what is healthy or normal: A student might think that getting tattoos all over his body is totally cool, but if his parents disagree, they don't get to accuse him of having a mental disorder! However, the definition does include the behavior of people who think they are perfectly fine yet who cause enormous harm to themselves or others, such as a child who is unable to control the desire to set fires, compulsive gamblers who lose the family's savings, or people who hear voices telling them to stalk a celebrity day and night.

The main criticism of defining mental disorder as “harmful dysfunction” is that it is often unclear what the evolutionary function or underlying pathology of a particular harmful behavior or emotional state might be. In this chapter, therefore, we define mental disorder as any condition that causes a person to suffer, is self-destructive, seriously impairs a person's ability to work or get along with others, or makes a person unable to control the impulse to endanger others. By this definition, many people will have some mental health problem in the course of their lives. To find out how psychologists define a mental disorder, watch the video What Does It Mean to Have a Mental Disorder?

Watch

What Does It Mean to Have a Psychological Disorder?

Dilemmas of Diagnosis

Even with a general definition of mental disorder, classifying mental disorders into distinct categories is not an easy job. In this section, we will see why this is so.

Classifying Disorders: The DSM The standard reference manual used to diagnose mental disorders is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), published by the American Psychiatric Association (2013). The DSM's primary aim is descriptive: to provide clear diagnostic categories so that clinicians and researchers can agree on which disorders they are talking about and then can study and treat these disorders. Its diverse diagnostic categories include attention-deficit disorders, disorders due to brain damage from disease or drugs, eating disorders, problems with sexual identity or behavior, impulse-control disorders (such as violent rages and pathological gambling or stealing), personality disorders, and sleep–wake disorders, along with other major disorders we will discuss in this chapter.

The DSM lists the symptoms of each disorder and, wherever possible, gives information about the typical age of onset, predisposing factors, course of the disorder, prevalence of the disorder, sex ratio of those affected, and cultural issues that might affect diagnosis. In making a diagnosis, clinicians are encouraged to take into account many factors, such as the client's personality traits, medical conditions, stresses at work or home, and the duration and severity of the problem (Caspi et al., 2014; Galatzer-Levy & Bryant, 2013).

The DSM has had an extraordinary impact worldwide. Virtually all textbooks in psychiatry and psychology base their discussions of mental disorders on the DSM. With each new edition of the manual, the number of mental disorders has grown. The first edition, published in 1952, was only 86 pages long and contained about 100 diagnoses. The DSM-IV, published in 1994 and slightly revised in 2000, is 900 pages long and contains nearly 400 diagnoses of mental disorder. The DSM-5, published in 2013, is 947 pages and contains about the same number of diagnoses.

What is the reason for this explosion of mental disorders? A primary reason is economic: Insurance companies require clinicians to assign their clients an appropriate DSM code number for whatever the client's problem is, which puts pressure on compilers of the manual to add more diagnoses so that physicians and psychologists will be compensated and patients will be covered (Zur & Nordmarken, 2008).

The DSM affects you in ways you probably can't imagine. Its influence is reflected in the casual way that people today talk of someone's being “bipolar,” having “a touch of Asperger's,” “being a borderline,” or suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). As we will see, some of its diagnostic categories became cultural fads that spread like wildfire, causing much harm before the fires were extinguished. Because of the DSM's powerful influence, therefore, we want you to understand its limitations and some of the problems that are built into the effort to classify and label mental disorders.

The danger of overdiagnosis. If you give a young child a hammer, the old saying goes, it will turn out that everything he runs into needs pounding. Likewise, say critics, if you give mental health professionals a diagnostic label, it will turn out that everyone they run into has the symptoms of the new disorder.

Consider attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a diagnosis given to children and adults who are impulsive, messy, restless, and easily frustrated and who have trouble concentrating. Since ADHD was added to the DSM, the number of cases has skyrocketed in the United States, where it is diagnosed at least 10 times as often as it is in Europe. Critics fear that parents, teachers, and mental health professionals are overdiagnosing this condition, especially in boys, who make up 80–90 percent of all ADHD cases. The critics argue that normal boyish behavior—being rambunctious, refusing to nap, being playful, not listening to teachers in school—has been turned into a psychological problem (Cummings & O'Donohue, 2008; Panksepp, 1998). A longitudinal study of more than a hundred 4- to 6-year-olds found that the number of children who met the criteria for ADHD declined as the children got older (Lahey et al., 2005). Those who truly had the disorder remained highly impulsive and unable to concentrate, but others simply matured. Now ADHD is being overdiagnosed in adults as well. Have trouble concentrating? Bored? You could get diagnosed with ADHD (Frances, 2013).

If you've ever watched a group of boys, you know that they can often be impulsive, messy, and restless. Those qualities are also part of the diagnosis of ADHD. How would you distinguish between normal boisterous boy behavior and a clinical diagnosis? Does having a diagnostic label available make it easier to apply a diagnosis when one might not be called for?

In children, an alarming example of overdiagnosis involves bipolar disorder, which occurs primarily in adolescents and adults. Childhood bipolar disorder (CBD), a diagnosis that was based on small, inconclusive studies, was promoted by one psychiatrist who received multimillion-dollar payments from a pharmaceutical company that makes a powerful, risky antipsychotic drug often prescribed for the disorder (Greenberg, 2008). As soon as “childhood bipolar disorder” had a name, the number of diagnoses rose from 20,000 to 800,000 in just 1 year (Leibenluft & Rich, 2008; Moreno et al., 2007). “The CBD fad is the most shameful episode in my forty-five years of observing psychiatry,” wrote Allen Frances (2013), an eminent psychiatrist who directed revision of the DSM-IV; the DSM-5 removed this diagnosis.

The power of diagnostic labels. After a person has been given a diagnosis, other people begin to see that person primarily in terms of the label and overlook other possible explanations. When a rebellious, disobedient teenager is diagnosed as having “oppositional-defiant disorder” or a child is labeled as having “disruptive mood dysregulation disorder,” people tend to regard those problems as being inherent in the individual. But maybe the teenager is “defiant” because he has been mistreated or his parents don't listen to him, and maybe the child has “disruptive” temper outbursts because his parents are not setting limits. And after a teenager or child is labeled, observers tend to ignore changes in his or her behavior, all the times the teenager is not being defiant or the child is getting along fine without having tantrums.

On the other hand, many people welcome having a diagnostic label applied to them. Being given a diagnosis reassures those who are seeking an explanation for their emotional symptoms or those of their children (“Whew! So that's what it is!”). Some people even come to identify themselves according to a diagnosis and make it a central focus of their lives. Many people with Asperger's syndrome have established websites and support groups and have even adopted a nickname (“Aspies”). What happens, then, when the label vanishes? The DSM-5 has removed Asperger's as a specific diagnosis, enfolding it into the spectrum of autism disorders, over the protests of many people who want the label.

The confusion of serious mental disorders with normal problems. The DSM is not called “The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and a Whole Bunch of Everyday Problems.” Yet each edition of the DSM has added more everyday problems, including, in DSM-5, “caffeine intoxication” and “parent–child relational problem.” Some critics fear that by lumping together normal difficulties with true mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia and major depression, the DSM implies that everyday problems are comparable to serious mental disorders (Houts, 2002).

A related concern is that the DSM-5 has loosened the criteria needed for making a diagnosis, thereby increasing the number of people who can be labeled with a disorder. The DSM-5 has added binge-eating disorder, whose symptoms include “eating until feeling uncomfortably full” or “when not feeling physically hungry.” Who would not receive this diagnosis on occasion? One of the most vehement protests regarding DSM-5 changes was on just this issue of moving the goalposts for a diagnosis. In the past, people who were grieving over the death of a loved one were not considered to have clinical depression unless the grief became prolonged or incapacitating. However, the DSM-5 removed the “bereavement exemption” from diagnoses of major depression. This change outraged many mental health professionals, who objected to the blurring of the symptoms of normal bereavement with those of severe depression (Greenberg, 2008). To the editors of the DSM-5, depression is depression, whatever generates it. To the protesters, this change turns an understandable and universal reason for human sorrow into a mental disorder (Horwitz & Wakefield, 2007).

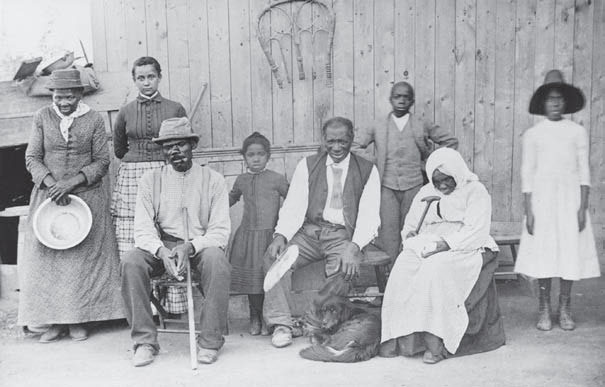

The illusion of objectivity. Finally, some psychologists argue that the whole enterprise of the DSM is a vain attempt to impose a veneer of science on an inherently subjective process (Gomory et al., 2011; Horwitz & Grob, 2011; Houts, 2002; Kutchins & Kirk, 1997; Tiefer, 2004). Many decisions about what to include as a disorder, say these critics, are based not on empirical evidence but on group consensus. The problem is that group consensus often reflects prevailing attitudes and prejudices rather than objective evidence. It is easy to see how prejudice operated in the past. In the early years of the 19th century, a physician argued that many slaves were suffering from drapetomania, an urge to escape from slavery (Landrine, 1988). (He made up the word from drapetes, the Latin word for “runaway slave,” and mania, meaning “mad” or “crazy.”) Thus, doctors could assure slave owners that a mental illness, not the intolerable condition of slavery, made slaves seek freedom. This diagnosis was very convenient for slave owners. Today, of course, we know that “drapetomania” was foolish and cruel.

Harriet Tubman (on the left) poses with some of the people she helped to escape from slavery on her “Underground Railroad.” Slaveholders welcomed the idea that Tubman and others who insisted on their freedom had a mental disorder called “drapetomania.”

Over the years, psychiatrists have quite properly rejected many other “disorders” that reflected cultural prejudices, such as lack of vaginal orgasm, childhood masturbation disorder, and homosexuality. But critics argue that some DSM diagnoses continue to be affected by prejudices and values, as when clinicians try to decide if wanting to have sex “too often” or “not often enough” indicates a mental disorder (Wakefield, 2011). Emotional problems allegedly associated with menstruation remain in the DSM-5, but behavioral problems associated with testosterone have never been considered for inclusion. In short, critics maintain, many diagnoses continue to stem from cultural biases about what constitutes normal or appropriate behavior.

Supporters of the DSM maintain that it is important to help clinicians distinguish among disorders that share certain symptoms, such as anxiety, irritability, or delusions, so they can be diagnosed reliably and treated properly. And they fully acknowledge that the boundaries between “normal problems” and “mental disorders” are fuzzy and often difficult to determine (Helzer et al., 2008; McNally, 2011). That is why the DSM-5 editors decided to classify many disorders along a spectrum of symptoms, and in degrees from mild to severe, rather than as discrete categories.

Dilemmas of Determination

LO 15.1.C Explain the theoretical basis of projective tests, and identify the problems associated with these techniques.

Listen to the Audio

Clinical psychologists and psychiatrists usually arrive at a diagnosis by interviewing a patient and observing the person's behavior when he or she arrives at the office, hospital, or clinic. But many also use psychological tests to help them determine a diagnosis. Such tests are also commonly used in schools (e.g., to determine whether a child has a learning disorder) and in court settings (e.g., to try to determine which parent should have custody in a divorce case, whether a child has been sexually abused, or whether a defendant is mentally competent).

Projective TestsProjective tests consist of ambiguous pictures, sentences, or stories that the test taker interprets or completes. A child or adult may be asked to draw a person, a house, or some other object, or to finish a sentence (such as “My father . . .” or “Women are . . .”). The psychodynamic assumption behind projective tests is that the person's unconscious feelings will be “projected” onto the test and revealed in the person's responses.

Projective tests can help clinicians establish rapport with their clients and can encourage clients to open up about anxieties and conflicts they might be ashamed to discuss. But the evidence is overwhelming that these tests lack reliability and validity, which makes them inappropriate for their most common uses—assessing personality traits or diagnosing mental disorders. They lack reliability because different clinicians often interpret the same person's scores differently, perhaps projecting their own beliefs and assumptions when they decide what a specific response means. The tests have low validity because they fail to measure what they are supposed to measure (Hunsley, Lee, & Wood, 2015). One reason is that responses to a projective test are significantly affected by sleepiness, hunger, medication, worry, verbal ability, the clinician's instructions, the clinician's personality (friendly and warm, or cool and remote), and other events occurring that day.

One of the most popular projectives is the Rorschach inkblot test, which was devised by Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach in 1921. It consists of 10 cards with symmetrical abstract patterns, originally formed by spilling ink on a piece of paper and folding it in half. The test taker reports what she or he sees in the inkblots, and the clinician interprets the answers according to the symbolic meanings emphasized by psychodynamic theories. Although the Rorschach is widely used among clinicians, efforts to confirm its reliability and validity have repeatedly failed. The Rorschach does not reliably diagnose depression, posttraumatic stress reactions, personality disorders, or serious mental disorders. Claims of the Rorschach's success often come from testimonials at workshops where clinicians are taught how to use the test, which is hardly an impartial way of assessing it (Wood et al., 2003).

A Rorschach inkblot. What do you see in it?

Many psychotherapists and clinical social workers use projective tests with young children to help them express feelings they cannot reveal verbally. But during the 1980s, some of them began using projective methods for another purpose: to determine whether a child had been sexually abused. They claimed they could identify a child who had been abused by observing how the child played with “anatomically detailed” dolls (dolls with realistic genitals), and that is how many of them testified in hundreds of court cases (Ceci & Bruck, 1995).

Unfortunately, these therapists had not tested their beliefs by using a fundamental scientific procedure: comparison with a control group. They had not asked, “How do nonabused children play with these dolls?” When psychological scientists conducted controlled research to answer this question, they found that large percentages of nonabused children are also fascinated with the doll's genitals. They will poke at them, grab them, pound sticks into a female doll's vagina, and do other things that alarm adults. The crucial conclusion was that you cannot reliably diagnose sexual abuse on the basis of children's doll play (Bruck, Ceci, & Francoeur, 2000; Hunsley, Lee, & Wood, 2015; Koocher et al., 1995). Over the years, clinicians have therefore devised other kinds of “props” and toys that they hope will facilitate children's reporting of having been molested. Unfortunately, studies involving alleged abuse victims, children who have been through medical exams, and children who have participated in lab experiments have failed to find consistent evidence that props improve young children's ability to make accurate reports. On the contrary, these props actually elevate the risk of false reports of touch (Poole, Bruck, & Pipe, 2011). You can see how someone who does not understand the problems with projective tests, or who lacks an understanding of children's cognitive limitations, might make inferences about a child's behavior that are dangerously wrong.

For years, many therapists used anatomically detailed dolls as a projective test to determine whether a child had been sexually abused. But the empirical evidence, including studies of nonabused children in a control group, shows that this practice is simply not valid. It can lead to false allegations because it often misidentifies nonabused children who are merely fascinated with the dolls' genitals.

Another situation in which projective tests are used widely but often inappropriately is in child custody assessments because judges long for an objective way to determine which parent is better suited to have custody. But when a panel of psychological scientists impartially examined the leading psychological assessment measures, most of which are projective tests, they found that “these measures assess ill-defined constructs, and they do so poorly, leaving no scientific justification for their use in child custody evaluations” (Emery, Otto, & O'Donohue, 2005).

Objective Tests Many clinicians use objective tests (inventories), standardized questionnaires that ask about the test taker's behavior and feelings. Inventories are generally more reliable and valid than either projective methods or subjective clinical judgments (Dawes, 1994; Meyer et al., 2001). The leading objective test of major depression is the Beck Depression Inventory and the most widely used diagnostic assessment for personality and emotional disorders is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI). The MMPI is organized into 10 categories, or scales, covering such problems as depression, paranoia, schizophrenia, and introversion. Four additional validity scales indicate whether a test taker is likely to be lying, defensive, or evasive while answering the items.

Inventories are only as good as their questions and how knowledgeably they are interpreted. Some test items on the MMPI fail to consider differences among cultural, regional, and socioeconomic groups. For instance, Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Argentine respondents score differently from non–Hispanic Americans, on average, on the Masculinity–Femininity Scale. This difference does not reflect emotional problems but traditional Latino attitudes toward sex roles (Cabiya et al., 2000). Also, the MMPI sometimes labels a person's responses as evidence of mental disorder when they are a result of understandable stresses and conflicts, such as during divorce or other legal disputes, when participants are upset and angry (Guthrie & Mobley, 1994; Leib, 2008). However, testing experts continue to improve the reliability and validity of the MMPI in clinical assessment, restructuring the clinical scales to reflect current research on mental disorders and personality traits (Butcher & Perry, 2008; Sellbom, Ben-Porath, & Bagby, 2008).

We turn now to a closer examination of some of the disorders described in the DSM. Because we cannot cover all of them in one chapter, we have singled out several that illustrate the range of psychological problems that afflict humanity, from the common to the very rare.