15.6

Drug Abuse and Addiction

The DSM-5 category of substance-related and addictive disorders covers the abuse of 10 classes of drugs, including alcohol, caffeine, hallucinogens, inhalants, cocaine, and tobacco, and adds “other (or unknown) substances,” in case as-yet-unidentified ways of getting high turn up. All drugs that are used in a way that is self-destructive or impairs a person's ability to hold a job, care for children, get along with others, or complete schoolwork are alike in activating the brain's reward system. The DSM-5 has also added “gambling disorder” in this category, on the grounds that compulsive gambling activates the brain's reward mechanisms just as drugs do. But it relegated “Internet gaming disorder” to the appendix, as a condition warranting further study, and decided not to include excessive behavioral patterns popularly called “sex addiction,” “shopping addiction,” or “exercise addiction” because, as the manual explains, there is little evidence that these constitute mental disorders.

In this section, focusing primarily on the example of alcoholism, we will consider the two dominant approaches to understanding addiction and drug abuse—the biological model and the learning model—and then see how they might be reconciled.

Philip Seymour Hoffman was a talented actor who received critical acclaim in films such as The Big Lebowski, Capote, and Hunger Games. Sadly, he also struggled with drug addiction throughout his life, going through periods of sobriety and abuse since young adulthood. Hoffman died in 2014 from “acute mixed drug intoxication.” Heroin, cocaine, amphetamines, and benzodiazepines were found in his system.

Biology and Addiction

The biological model, also called the disease model, holds that addiction, whether to alcohol or any other drug, is due primarily to a person's neurology and genetic predisposition. The clearest example of the biology of addiction is nicotine. Although smoking rates have declined over the past 50 years, nicotine addiction remains one of the most serious health problems worldwide. Unlike other addictions, it can begin quickly, within a month after the first cigarette—and for some teenagers, after only one cigarette—because nicotine almost immediately changes neuron receptors in the brain that react chemically to the drug (DiFranza, 2008). Genes produce variation in these nicotine receptors, which is one reason that some people are especially vulnerable to becoming addicted to cigarettes and have tremendous withdrawal symptoms when they try to give them up, whereas other people, even if they have been heavy smokers, can quit cold turkey (Bierut et al., 2008).

For alcoholism, the picture is more complicated. Genes are involved in some kinds of alcoholism but not all. There is a heritable component in the kind of alcoholism that begins in early adolescence and is linked to impulsivity, antisocial behavior, and criminality (Dick, 2007; Dick et al., 2008; Schuckit et al., 2007; Verhulst, Neale, & Kendler, 2015), but not in the kind of alcoholism that begins in adulthood and is unrelated to other disorders. Genes also affect alcohol “sensitivity”—how quickly people respond to alcohol, whether they tolerate it, and how much they need to drink before feeling high (Hu et al., 2008). In an ongoing longitudinal study of 450 young men, those who at age 20 had to drink more than others to feel any reaction were at increased risk of becoming alcoholic within the decade. This was true regardless of their initial drinking habits or family history of alcoholism (Schuckit, 1998; Schuckit et al., 2011).

In contrast, people who have a high sensitivity to alcohol are less likely to drink to excess, and this may partly account for ethnic differences in alcoholism rates. One genetic factor causes low activity of an enzyme involved in the metabolism of alcohol. People who lack this enzyme respond to alcohol with unpleasant symptoms, such as flushing and nausea. This genetic protection is common among Asians but rare among Europeans, which may be one reason that rates of alcoholism are much lower in Asian than in Caucasian populations; the Asian sensitivity to alcohol discourages them from drinking a lot (Heath et al., 2003). Not all Asians are the same in this regard, however. Korean American college students have higher rates of alcohol-use disorders and family histories of alcoholism than do Chinese American students (Duranceaux et al., 2008). And Native Americans have the same genetic protection that Asians do, yet they have much higher rates of alcoholism.

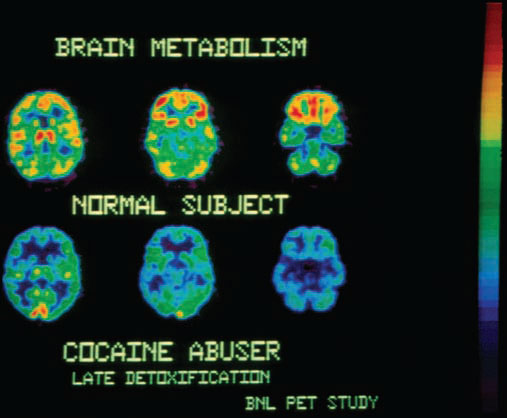

For years, the usual way of looking at biological factors and addiction was to assume that the first causes the second. However, the relationship also works the other way: Addictions can result from the abuse of drugs (Crombag & Robinson, 2004; Lewis, 2011). Many people become addicted not because their brains have led them to abuse drugs, but because the abuse of drugs has changed their brains. Over time, the repeated jolts of pleasure-producing dopamine modify brain structures in ways that maximize the appeal of the drug (or of other addictive experiences such as gambling), minimize the appeal of other rewards, and disrupt cognitive functions such as working memory, self-control, and decision making, which is why addictive behavior comes to feel automatic (Houben, Wiers, & Jansen, 2011; Lewis, 2011). Heavy use of cocaine, alcohol, and other drugs reduces the number of receptors for dopamine and creates the feeling of having a compulsion to keep using the drug (Volkow et al., 2001; see Figure 15.3). In the case of alcoholism, heavy drinking also reduces the level of painkilling endorphins, produces nerve damage, and shrinks the cerebral cortex. These changes can then create a craving for more liquor, and the person stays intoxicated for longer and longer times, drinking not for pleasure at all but simply to appease the craving (Heilig, 2008). Even after addicts have gone through detox and remained drug-free, their dopamine circuits remain blunted.

Figure 15.3

The Addicted Brain

PET studies show that the brains of cocaine addicts have fewer receptors for dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved in pleasurable sensations. (The more yellow and red in the brain image, the more receptors.) The brains of people addicted to methamphetamine, alcohol, and even food show a similar dopamine deficiency.

Thus, drug abuse, which begins as a voluntary action, can turn into drug addiction, a compulsive behavior that addicts find exceedingly difficult to control.

Learning, Culture, and Addiction

Many people assume that if abnormalities are discovered in the brains of addicts, perhaps because of genetic reasons, nothing can be done about it. Yet consider the results from a team of scientists who studied the brains of people addicted to stimulants and their biological siblings who had no history of chronic drug abuse (Ersche et al., 2012). The addicts and their siblings revealed abnormalities in the parts of the brain involved in self-control. Indeed, impulsiveness, an inability to control one's immediate craving for something, is characteristic of addicts (and others who cannot control eating, gambling, texting, or other behaviors). But what enables their equally vulnerable siblings to resist temptation and addiction? Likely candidates include resilience, experience, peer groups, the ability to manage frustration, and strong coping skills (Volkow & Baler, 2012). The learning model examines the role of the environment, learning, and culture in encouraging or discouraging these factors and others involved in addiction. Four lines of research support the learning model:

Addiction patterns vary according to cultural practices. Alcoholism is much more likely to occur in societies that forbid children to drink but condone drunkenness in adults (as in Ireland) than in societies that teach children how to drink responsibly and moderately but condemn adult drunkenness (as in Italy, Greece, and France). In cultures with low rates of alcoholism (except for those committed to a religious rule that forbids use of all psychoactive drugs), adults demonstrate correct drinking habits to their children, gradually introducing them to alcohol in safe family settings. Alcohol is not used as a rite of passage into adulthood. Abstainers are not sneered at, and drunkenness is not considered charming, comical, or manly; it is considered stupid and obnoxious (Peele, 2010; Peele & Brodsky, 1991; Zapolsky et al., 2014).

The cultural environment may be especially crucial for the development of alcoholism among young people with a genetic vulnerability to alcohol (Schuckit et al., 2008). In one such group of 401 American Indian youths, those who later developed drinking problems lived in a community in which heavy drinking was encouraged and modeled by their parents and peers. But those who felt a cultural and spiritual pride in being Native American, and who were strongly attached to their religious traditions, were less likely to develop drinking problems, even when their parents and peers were encouraging them to drink (Yu & Stiffman, 2007).

The disease model assumes that if children are given even a taste of a drink or a drug, they are more likely to become addicted or a drug abuser. The learning model assumes that the cultural context is crucial in determining whether people will become addicted or learn to use drugs moderately. In fact, when children learn the rules of social drinking with their families, as at Jewish Passover seders (left), alcoholism rates are much lower than in cultures in which drinking occurs mainly in bars or in privacy. Similarly, when marijuana is used as part of a religious tradition, as it is by members of the Rastafarian church in Jamaica, use of the “wisdom weed” does not lead to addiction or harder drugs.

Addiction rates can rise or fall rapidly as a culture changes. In colonial America, the average person drank two to three times the amount of liquor consumed today, yet alcoholism was not a serious problem. Drinking was a universally accepted social activity; families drank and ate together. Alcohol was believed to produce pleasant feelings and relaxation, and Puritan ministers endorsed its use (Critchlow, 1986). Then, between 1790 and 1830, when the American frontier was expanding, drinking came to symbolize masculine independence and toughness. The saloon became the place for drinking away from home. As people stopped drinking in moderation with their families, alcoholism rates shot up, as the learning model would predict.

Substance abuse and addiction problems also increase when people move from their culture of origin into another that has different drinking rules (Westermeyer, 1995). In most Latino cultures, such as those of Mexico and Puerto Rico, drinking and drunkenness are considered male activities. Latina women tend to drink rarely, if at all; they have few drinking problems until they move into an Anglo environment, when their rates of alcoholism rise (Canino, 1994). Likewise, when norms within a culture change, so may drinking habits and addiction rates. The cultural norm for American college women was previously low to moderate drinking; today, they are more likely to abuse alcohol than they ever used to. One reason is that the culture of many college campuses encourages drinking games, binge drinking (having at least four to five drinks in a 2-hour session), and getting drunk, especially among members of fraternities and sororities (Courtney & Polich, 2009). When everyone around you is downing shots one after another or playing Beer Pong, it's hard to say, “I'd really rather just have one drink.”

Policies of total abstinence tend to increase rates of addiction rather than reduce them. In the United States, the temperance movement of the early 20th century held that drinking inevitably leads to drunkenness, and drunkenness to crime. The solution it won for the Prohibition years (1920–1933) was national abstinence. But this victory backfired: Again in accordance with the learning model, Prohibition reduced rates of drinking overall, but it increased rates of alcoholism among those who did drink. Because people were denied the opportunity to learn to drink moderately, they drank excessively when given the chance (McCord, 1989). And, of course, when a substance is forbidden, it becomes more attractive to some people. Most schools in the United States have zero-tolerance policies regarding marijuana and alcohol, but large numbers of students have tried them or use them regularly. In fact, rates of binge drinking have increased the most among underage students, who are legally forbidden to drink until age 21.

Not all addicts have withdrawal symptoms when they stop taking a drug. When heavy users of a drug stop taking it, they often suffer such unpleasant symptoms as nausea, abdominal cramps, depression, and sleep problems, depending on the drug. But these symptoms are far from universal. During the Vietnam War, nearly 30 percent of U.S. soldiers were taking heroin in doses far stronger than those available on the streets of American cities. These men believed themselves to be addicted, and experts predicted a drug-withdrawal disaster among the returning veterans. It never materialized; over 90 percent of the men simply gave up the drug, without significant withdrawal pain, when they came home to new circumstances (Robins, Davis, & Goodwin, 1974). Subsequent studies over the years find that this response is the norm, not the exception (Heyman, 2009, 2011), which is strong evidence against the idea that addiction is always a chronic disease. The majority of people who are dependent on cigarettes, tranquilizers, or painkillers are able to stop taking these drugs without outside help and without severe withdrawal symptoms (Prochaska, Norcross, & DiClemente, 1994). Many people find this information startling, even unbelievable. That is because people who can quit without help aren't entering programs to help them quit, so they are invisible to the general public and to the medical world. But they have been identified in random-sample community surveys.

One reason that many people are able to quit abusing drugs is that the environment in which a drug is used (the setting) and a person's expectations (mental set) have a powerful influence on the drug's physiological effects as well as its psychological ones. You might think a lethal dose of, say, amphetamines would be the same wherever the drug was taken. But studies of mice have found that the lethal dose varies depending on the mice's environment—whether they are in a large or small test cage, or whether they are alone or with other mice. The physiological response of human addicts to certain drugs also changes, depending on whether the addicts are in a “druggy” environment, such as a crack house, or an unfamiliar one (Crombag & Robinson, 2004; Siegel, 2005). This is the primary reason that addicts need to change environments if they are going to kick their habits. It's not just to get away from a peer group that might be encouraging them, but also to literally change and rewire their brain's response to the drug.

Test Your Motives for Drinking

[[For Revel: Insert Interactive 15.6]]

Addiction does not depend on properties of the drug alone but also on the reasons for taking it. For decades, doctors were afraid to treat people with chronic pain by giving them narcotics, fearing they would become addicted. As a result of this belief, millions of people were condemned to live with chronic suffering from back pain, arthritis, nerve disorders, and other conditions—and pain impedes healing. But then researchers learned that the great majority of pain sufferers use morphine and other opiates not to escape from the world but to function in the world, and they do not become addicted (Portenoy, 1994; Raja, 2008). (Of course, powerful opiates should not be prescribed for mild pain, and they must be carefully monitored.)

In the case of alcohol, people who drink simply to be sociable or to relax when they have had a rough day are unlikely to become addicted. Problem drinking occurs when people drink to disguise or suppress their anxiety or depression, when they drink alone to drown their sorrows and worries, or when they want an excuse to abandon inhibitions (Cooper et al., 1995; Mohr et al., 2001). College students who feel alienated and uninvolved with their studies are more likely than their happier peers to go out drinking with the conscious intention of getting drunk.

In many cases, then, the decision to start abusing drugs depends more on people's motives, and on the norms of their peer group and culture, than on the chemical properties of the drug itself.

Debating the Causes of Addiction

The biological and learning models both contribute to our understanding of drug use and addiction. Yet, among many researchers and public health professionals, these views are quite polarized, especially when it comes to thinking about treatment (see Review15.1). Such polarization often leads to either–or thinking on a national scale: Either complete abstinence is the solution, or it is the problem. For example, those who advocate the biological (disease) model say that alcoholics and problem drinkers must abstain completely, and that young people should not be permitted to drink, even at home with their parents, until they are 21. Those who champion the learning model argue that most problem drinkers can learn to drink moderately if they learn safe drinking skills, acquire better ways of coping with stress, avoid situations that evoke conditioned responses to using drugs, and avoid friends who pressure them to drink excessively. Besides, they ask, how are young people going to learn to drink safely and moderately if they don't first do so at home or in other safe environments (Denning, Little, & Glickman, 2004; Glaser, 2014; Rosenberg, 1993)?

How can we assess these two positions critically? Because alcoholism, problem drinking, and other kinds of substance abuse occur for many reasons, neither model offers the only solution. In the case of alcohol, many problem drinkers cannot learn to drink moderately, especially if they have been drinking heavily for many years, by which time, as we saw earlier, physiological changes in their brains and bodies may have turned them from abusers into addicts. Unfortunately, total-abstinence groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) are ineffective for many people. According to its own surveys and those conducted independently, one-third to one-half of all people who join AA drop out. Many of these dropouts benefit from programs such as Harm Reduction, which teach people how to drink moderately and keep their drinking under control (Witkiewitz, Walthers, & Marlatt, 2013).

So instead of asking, “Can problem drinkers learn to drink moderately?” perhaps we should ask, “What are the factors that make it more or less likely that someone can learn to control problem drinking?” Problem drinkers who are most likely to become moderate drinkers have a history of less severe dependence on the drug. They lead more stable lives and have jobs and families. In contrast, those who are at greater risk of alcoholism (or other drug abuse) have these risk factors: (1) They have a genetic vulnerability to the drug or have been using it long enough for it to have damaged or changed their brains; (2) they believe that they have no control over their drinking or drug use; (3) they live in a culture or a peer group that promotes and rewards binge drinking or discourages moderate drug use; and (4) they have come to rely on the drug as a way of avoiding problems, suppressing anger or fear, or coping with stress.