15.7

Dissociative Identity Disorder

When most people say “I'm just not myself today,” it usually means they're in a bad mood, tired, or otherwise preoccupied. As a clinical diagnosis, “not being yourself” might imply a condition that has captured the public's imagination, yet left most psychological scientists highly skeptical.

Can You See the Real Me?

One of the most controversial diagnoses ever to arise in psychiatry and psychology is dissociative identity disorder (DID), formerly and still popularly called multiple personality disorder (MPD). This label describes the apparent emergence, within one person, of two or more distinct identities, each with its own name, memories, and personality traits. Cases of multiple personality portrayed on TV, in books, and in films such as The Three Faces of Eve and Sybil have captivated the public for years, and they still do. In 2009, Showtime televised The United States of Tara, a series in which a woman with a very tolerant husband and two teenagers keeps breaking into one of her three identities—a sex-and-shopping-mad teenage girl, a gun-loving redneck male, and a 1950s-style homemaker.

Some psychiatrists and clinical psychologists take dissociative identity disorder very seriously, believing that it originates in childhood as a means of coping with sexual abuse or other traumatic experiences (Gleaves, 1996). In their view, the trauma produces a mental “splitting” (dissociation): One personality emerges to handle everyday experiences, and another personality (called an “alter”) to cope with the bad ones. During the 1980s and 1990s, clinicians who believed a client had a “multiple personality” often used highly suggestive techniques to “bring out the alters,” such as hypnosis, drugs, and even outright coercion (McHugh, 2008; Rieber, 2006; Spanos, 1996). Psychiatrist Richard Kluft (1987) wrote that efforts to determine the presence of alters may require “between 2½ and 4 hours of continuous interviewing. Interviewees must be prevented from taking breaks to regain composure. . . . In one recent case of singular difficulty, the first sign of dissociation was noted in the 6th hour, and a definitive spontaneous switching of personalities occurred in the 8th hour.”

Mercy! After 8 hours of “continuous interviewing” without a single break, how many of us wouldn't do what the interviewer wanted? Clinicians who conducted such interrogations argued that they were merely permitting other personalities to reveal themselves, but skeptical psychological scientists countered that they were actively creating other personalities through suggestion and sometimes even intimidation with vulnerable clients who had other psychological problems (Lilienfeld & Lynn, 2015).

Psychological scientists have shown that “dissociative amnesia,” the mechanism that supposedly causes traumatized children to repress their ordeal and develop several identities as a result, lacks historical and empirical support (Lynn et al., 2012). For one thing, truly traumatic experiences are remembered all too long and all too well (McNally, 2003; Pope et al., 2007). For another, scientific studies, as opposed to subjective case studies, have failed to confirm that the alleged personalities in DID have amnesia for what the others have done. In a study that compared nine DID patients with healthy controls and with another group of actors simulating DID, the patients were just as likely as the others to transfer autobiographical memories between identities when this information was needed as part of a task. Although patients said that they could not recall the autobiographical details of their alters, the results indicated that they could (Huntjens, Verschuere, & McNally, 2012).

Putting the Pieces Together

So what is DID? The evidence suggests that it is a homegrown culture-bound syndrome. Only a handful of multiple personality cases had ever been diagnosed anywhere in the world before 1980; yet by the mid-1990s, tens of thousands of cases had been reported, mostly in the United States and Canada. MPD became a lucrative business, benefiting hospitals that opened MPD clinics, therapists who had a new disorder to treat, and psychiatrists and patients who wrote best-selling books. Then, in the 1990s, as a result of numerous malpractice cases across the country, courts ruled, on the basis of the testimony of scientific experts in psychiatry and psychology, that MPD was being generated by the clinicians who believed in it. The MPD clinics in hospitals closed, psychiatrists became more wary, and the number of cases dropped sharply almost overnight. But the promoters of the diagnosis have never admitted they were mistaken; they continue to treat patients for it, and it remains in the DSM-5.

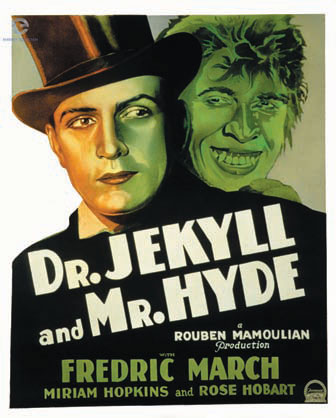

Why did the number of “alters” reported by people with DID increase over the years? In the earliest cases, multiple personalities came only in pairs. In the 1886 story of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, the kindly Dr. Jekyll turned into the murderous Mr. Hyde. At the height of the epidemic in North America in the 1990s, people were claiming to have several dozen, even hundreds, of alters, including demons, children, extraterrestrials, and animals.

No one disputes that some troubled, highly imaginative individuals can produce many different “personalities” when asked. But the sociocognitive explanation of DID holds that this phenomenon is simply an extreme form of the ability we all have to present different aspects of our personalities to others (Lilienfeld et al., 1999; Lynn et al., 2012). The disorder may seem very real to clinicians and their patients who believe in it, but in the sociocognitive view, it results from pressure and suggestion by clinicians, interacting with acceptance by vulnerable patients who find the idea that they have separate personalities a plausible explanation for their problems. The diagnosis of DID also allows some people to account for past sexual or criminal behavior that they now regret or find intolerably embarrassing; they can claim their “other personality did it.” In turn, therapists who believe in the diagnosis reward such patients with attention and praise for revealing more and more personalities—and a culture-bound syndrome is born (Hacking, 1995; Piper & Merskey, 2004). When Canadian psychiatrist Harold Merskey (1992) reviewed the published cases of MPD, he was unable to find a single one in which a patient had not been influenced by the therapist's suggestions or reports about the disorder in the media.

Even the famous case of “Sybil,” a huge hit as a book and television special, was a hoax. Sybil never had a traumatic childhood of sexual abuse, she did not have multiple personality disorder, and her “symptoms” were generated by pressure from her psychiatrist, Cornelia Wilbur, who injected her with heavy-duty drugs to get her to reveal other “personalities” (Borch-Jacobsen, 2009; Nathan, 2011). Yet, despite this pressure, even after several years Sybil failed to recall a traumatic childhood memory and was not producing many alters. Finally, she wrote to Wilbur, admitting she was “none of the things I have pretended to be. . . . I do not have any multiple personalities. . . . I do not even have a ‘double.’ . . . I am all of them. I have been essentially lying.” Wilbur replied that Sybil was merely experiencing massive denial and resistance, and threatened to withhold the drugs that Sybil had become addicted to. Sybil continued with therapy, and the two eventually produced the book that Wilber hoped would make her famous and wealthy. It did.

The story of MPD/DID offers a good lesson in critical thinking because it teaches us to be cautious about new diagnoses and previously rare disorders that suddenly catch fire in popular culture: to consider other explanations, examine assumptions and biases, and demand good evidence instead of simply accepting unskeptical media coverage.