15.8

Schizophrenia

We turn now to a last major category of psychological disorders, and one that has attracted a range of explanations since it was first given a name in the late 1800s (Kraepelin, 1896). Causes ranging from “a conflict between instincts” to “toxins in the endocrine system“ to social conditions to “the frustration of basic urges” have been proposed for what we now know is a brain disease (Brown & Menninger, 1940; Hunt, 1938; Lazell & Prince, 1929; Meyer, 1910–1911). To gain more insight into schizophrenic disorders, watch the video Living with a Disorder 2.

Watch

Living with a Disorder 2

Symptoms of Schizophrenia

In 1911, Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler coined the term schizophrenia to describe cases in which the personality loses its unity. Contrary to popular belief, people with schizophrenia do not have a “split” or “multiple” personality. Schizophrenia is a fragmented condition in which words are split from meaning, actions from motives, perceptions from reality. It is an example of a psychosis, a mental condition that involves distorted perceptions of reality and an inability to function in most aspects of life. The DSM-5's category is schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders, which includes conditions that vary in severity and duration.

Schizophrenia is the cancer of mental illness: elusive, complex, and varying in form. The DSM-5 criteria for the disorder list five core abnormalities:

Bizarre delusions. Some people with schizophrenia have delusions of identity, believing that they are Moses, Jesus, or another famous person. Some have paranoid delusions, taking innocent events—a stranger's cough, a helicopter overhead—as evidence that everyone is plotting against them. They may insist that their thoughts have been inserted into their heads by someone controlling them or are being broadcast on television. Some believe that ordinary objects or people are really something or someone else, perhaps extraterrestrials in disguise. Some have delusional beliefs; that a celebrity loves them, or that they have the secret plan for world peace, for example.

Hallucinations. People with schizophrenia suffer from false sensory experiences that seem intensely real, such as feeling insects crawling on their bodies or seeing snakes coming through walls. By far the most common hallucination is hearing voices; it is virtually a hallmark of the disease. Some sufferers are so tormented by these voices that they commit suicide to escape them. One man described how he heard as many as 50 voices cursing him, urging him to steal other people's brain cells, or ordering him to kill himself. Once he picked up a ringing telephone and heard them screaming, “You're guilty!” over and over. They yelled “as loud as humans with megaphones,” he told a reporter. “It was utter despair. I felt scared. They were always around” (Goode, 2003).

Disorganized, incoherent speech. People with schizophrenia often speak in an illogical jumble of ideas and symbols, linked by meaningless rhyming words or by remote associations called “word salads.” A patient of Bleuler's wrote, “Olive oil is an Arabian liquor-sauce which the Afghans, Moors and Moslems use in ostrich farming. The Indian plantain tree is the whiskey of the Parsees and Arabs. Barley, rice and sugar cane, called artichoke, grow remarkably well in India. The Brahmins live as castes in Baluchistan. The Circassians occupy Manchuria and China. China is the Eldorado of the Pawnees” (Bleuler, 1911/1950). Others make only brief, empty replies in conversation because of diminished thought rather than an unwillingness to speak.

Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior. Such behavior may range from childlike silliness to unpredictable and violent agitation. The person may wear three overcoats and gloves on a hot day, start collecting garbage, or hoard scraps of food. Some completely withdraw into a private world, sitting for hours without moving, a condition called catatonic stupor. Catatonic states can also produce frenzied, purposeless behavior that goes on for hours.

Negative symptoms. Many people with schizophrenia lose the motivation and ability to take care of themselves and interact with others; they may stop working or bathing, and become isolated and withdrawn. They lose expressiveness and thus seem emotionally flat; their facial expressions are unresponsive and they make poor eye contact. These symptoms are called “negative” because they involve the absence of normal behaviors or emotions.

Some signs of schizophrenia emerge early, in late childhood or early adolescence (Tarbox & Pogue-Geile, 2008), but the first full-blown psychotic episode typically occurs in late adolescence or early adulthood. In some individuals, the breakdown occurs suddenly; in others, it is more gradual, a slow change in personality. The more breakdowns and relapses the individual has had, the poorer the chances for recovery. Yet, contrary to stereotype, over 40 percent of people with schizophrenia do have one or more periods of recovery and go on to hold good jobs and have successful relationships, especially if they have strong family support and community programs (Harding, 2005; Hopper et al., 2007; Jobe & Harrow, 2010). What kind of mysterious disease could produce such a variety of symptoms and outcomes?

Inside a Shattered Mind

Origins of Schizophrenia

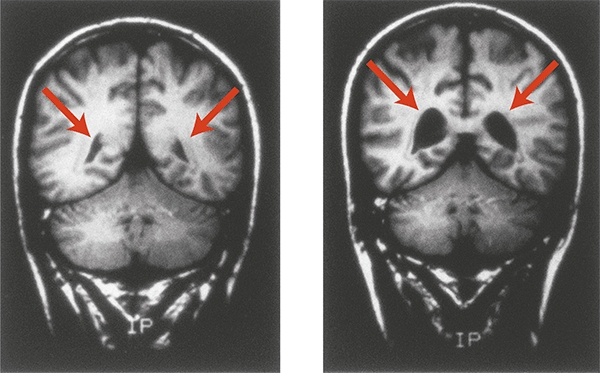

Schizophrenia is clearly a brain disease. It involves reduced volumes of gray matter in the prefrontal cortex and temporal lobes; abnormalities in the hippocampus; and abnormalities in neurotransmitters, neural activity, and disrupted communication between neurons in areas involving cognitive functioning, such as memory, decision making, and emotional processing (Karlsgodt, Sun, & Cannon, 2010). Most individuals with schizophrenia also show enlargement of the ventricles, spaces in the brain that are filled with cerebrospinal fluid (see Figure 15.4) (Dazzan et al., 2015). And they are more likely than nonschizophrenic individuals to have abnormalities in the thalamus, the traffic-control center that filters sensations and focuses attention (Andreasen et al., 1994; Gur et al., 1998). Many have deficiencies in the auditory cortex and Broca's and Wernicke's areas, all involved in speech perception and processing; these might explain the nightmare of voice hallucinations.

Figure 15.4

Schizophrenia and the Brain

People with schizophrenia are more likely to have enlarged ventricles (spaces) in the brain. These MRI scans of 28-year-old male identical twins show the difference in the size of ventricles between the twin without schizophrenia (left) and the one with schizophrenia (right).

Currently, researchers have identified three contributing factors in this disorder:

Genetic predispositions. Schizophrenia is highly heritable. A person has a much greater risk of developing the disorder if an identical twin develops it, even if the twins are reared apart (Gottesman, 1991; Gottesman et al., 2010; Heinrichs, 2005). Children with one schizophrenic parent have a lifetime risk of 7 to 12 percent, and children with two schizophrenic parents have a lifetime risk of 27 to 46 percent, compared to a risk in the general population of only about 1 percent (see Figure 15.5). Researchers all over the world are trying to identify the genes that might be involved in specific symptoms, such as hallucinations, sensitivity to sounds, cognitive impairments, and social withdrawal (Desbonnet, Waddington, & O'Tuathaigh, 2009; Tomppo et al., 2009). However, efforts to find the critical genes in schizophrenia have been difficult because several appear to be involved, and those are linked not only to schizophrenia but also to a range of other mental disorders, including autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, and even dyslexia (Fromer et al., 2014; Walker & Tessner, 2008; Williams et al., 2011).

Figure 15.5

Genetic Vulnerability to Schizophrenia

This graph, based on combined data from 40 European twin and adoption studies conducted over seven decades, shows that the closer the genetic relationship to a person with schizophrenia, the higher the risk of developing the disorder. (Based on Gottesman, 1991; see also Gottesman et al., 2010.)

Prenatal problems or birth complications. Damage to the fetal brain significantly increases the likelihood of schizophrenia later in life. Such damage may occur if the mother suffers from malnutrition; schizophrenia rates rise during times of famine, as happened in China and elsewhere (St. Clair et al., 2005). Damage may also occur if the mother gets the flu virus during the first 4 months of prenatal development, which triples the risk of schizophrenia (Brown et al., 2004). And it may occur if complications during birth injure the baby's brain or deprive it of oxygen (Cannon et al., 2000). Other nongenetic prenatal factors that increase the child's risk of schizophrenia, especially if they combine with each other, include maternal diabetes and emotional stress, having a father over age 55, birth during the winter months, and very low birth weight (King, St-Hilaire, & Heidkamp, 2010).

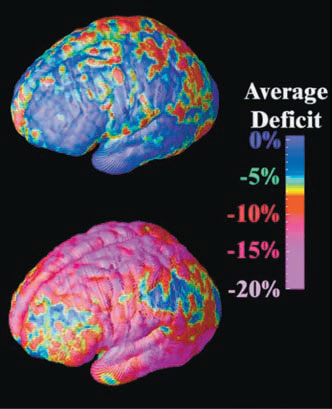

Biological events during adolescence. In adolescence, the brain undergoes a natural pruning-away of synapses. Normally, this pruning helps make the brain more efficient in handling the new challenges of adulthood. But it appears that schizophrenic brains aggressively prune away too many synapses, which may explain why the first full-blown schizophrenic episode typically occurs in adolescence or early adulthood. Healthy teenagers lose about 1 percent of the brain's gray matter between ages 13 and 18. But as you can see in Figure 15.6, in a study that tracked the loss of gray matter in the brain over 5 years, adolescents with schizophrenia showed much more extensive and rapid tissue loss, primarily in the sensory and motor regions (Thompson et al., 2001b). “We were stunned to see a spreading wave of tissue loss that began in a small region of the brain,” said Paul Thompson, who headed the study. “It moved across the brain like a forest fire, destroying more tissue as the disease progressed.”

Figure 15.6

The Adolescent Brain and Schizophrenia

These dramatic images highlight areas of brain-tissue loss in adolescents with schizophrenia over a 5-year span. The areas of greatest tissue loss (regions that control memory, hearing, motor functions, and attention) are shown in red and magenta. The brain of a person without schizophrenia (top) looks almost entirely blue (P. Thompson et al., 2001b).

Thus, the developmental pathway of schizophrenia is something of a relay. It starts with genetic predispositions, which may combine with prenatal risk factors or birth complications that affect brain development. The resulting vulnerability then awaits the next stage, synaptic pruning within the brain during adolescence (Walker & Tessner, 2008). Then, according to the vulnerability–stress model of schizophrenia, these biological changes usually interact with environmental stressors to trigger the disease. This model explains why one identical twin may develop schizophrenia but not the other: Both may have a genetic susceptibility, but only one may have been exposed to other risk factors in the womb, birth complications, or stressful life events. These and other aspects of this disorder are discussed in the video Schizophrenia.

Watch

Schizophrenia

We have come to the end of a long walk along the spectrum of psychological problems—from those that cause temporary difficulty, such as occasional anxiety or “caffeine intoxication,” to others that are severely disabling, such as major depression and schizophrenia. Psychologists strive to learn how biology, thought processes, culture, and experiences interact to produce these problems—the better to alleviate the suffering they cause.

[[For Revel: Insert Interactive 15.9]]