16.3

Evaluating Psychotherapy

Poor Murray! He is getting a little baffled by all these therapies. He wants to make a choice soon; no sense in procrastinating about that, too! Is there any scientific evidence, he wonders, that might help him decide which therapy or therapist will be best for him?

The Scientist–Practitioner Gap

Psychotherapy is, first and foremost, a relationship. Its success depends in part on the bond between the therapist and client, called the therapeutic alliance. When both parties respect and understand each other and agree on the goals of treatment, the client is more likely to improve (Klein et al., 2003). Now suppose that Murray has met a nice psychotherapist who seems smart and friendly, who he respects and understands, and who respects and understands Murray in return. Is a good alliance enough? How important is the kind of therapy that an individual practices?

These questions have generated a huge debate among clinical practitioners and psychological scientists. Many psychotherapists believe that trying to evaluate psychotherapy using standard empirical methods is an exercise in futility: Numbers and graphs, they say, cannot possibly capture the complex exchange that takes place between a therapist and a client. Psychotherapy, they maintain, is an art that you acquire from clinical experience; it is not a science. That’s why almost any method will work for some people (Laska, Gurman, & Wampold, 2014; Lilienfeld, 2014). Other clinicians argue that efforts to measure the effectiveness of psychotherapy ignore the fact that many patients have an assortment of emotional problems and need therapy for a longer time than research can reasonably allow (Marcus et al., 2014; Westen, Novotny, & Thompson-Brenner, 2004).

For their part, psychological scientists agree that therapy is often a complex process. But that is no reason, they argue, that it cannot be scientifically investigated just like any other complex psychological process, such as the development of language or personality (Crits-Christoph, Wilson, & Hollon, 2005; Kazdin, 2008). Moreover, they are concerned that when therapists fail to keep up with empirical findings in the field, their clients may suffer. It is crucial, scientists say, for therapists to be aware of research on the most beneficial methods for particular problems, on ineffective or potentially harmful techniques, and on topics relevant to their practice, such as memory and child development (Lilienfeld, Lynn, & Lohr, 2015).

Over the years, the breach between scientists and therapists has widened, creating what is commonly called the scientist–practitioner gap. One reason for the growing split has been the rise of professional schools that are not connected to academic psychology departments and that train students solely to do therapy. Graduates of these schools sometimes know little about research methods or even about research assessing different therapy techniques.

The scientist–practitioner gap has also widened because of the proliferation of unvalidated therapies in a crowded market. Some repackage established techniques under a new name; some are based on a therapist’s name and charisma. A blue-ribbon panel of clinical scientists, convened to assess the problem of the scientist–practitioner gap for the journal Psychological Science in the Public Interest, reported that the current state of clinical psychology is comparable to that of medicine in the early 1900s, when physicians typically valued personal experience over scientific research. The authors concluded that it is time for “a new accreditation system that demands high-quality science training as a central feature of doctoral training in clinical psychology” (Baker, McFall, & Shoham, 2008). The Academy of Psychological Clinical Science, an alliance of 49 clinical science graduate programs and nine clinical science internships, is making a concerted effort to institute just such a system (Bootzin, 2009).

Problems in Assessing Therapy Because so many therapies all claim to be successful, and because of economic pressures on insurers and rising health costs, clinical psychologists are increasingly being called on to provide empirical assessments of therapy. Why can’t you just ask people if the therapy helped them? The answer is that no matter what kind of therapy is involved, clients are motivated to tell you it worked. “Dr. Blitznik is a genius!” they will exclaim. “I would never have taken that job (or moved to Cincinnati, or found my true love) if it hadn’t been for Dr. Blitznik!” Every kind of therapy ever devised produces enthusiastic testimonials from people who feel it saved their lives.

The first problem with testimonials is that none of us can be our own control group. How do people know they wouldn’t have taken the job, moved to Cincinnati, or found true love anyway—maybe even sooner, if Dr. Blitznik had not kept them in treatment? Second, Dr. Blitznik’s success could be due to the placebo effect: The client’s anticipation of success and the buzz about Dr. B.’s fabulous new method might be the active ingredients, rather than Dr. B.’s therapy itself. Third, notice that you never hear testimonials from the people who dropped out, who weren’t helped, or who actually got worse. So researchers cannot be satisfied with testimonials, no matter how glowing. They know that thanks to the justification of effort effect, people who have put time, money, and effort into something will tell you it was worth it. No one wants to say, “Yeah, I saw Dr. Blitznik for 5 years, and boy, was it ever a waste of time.”

To guard against these problems, some clinical researchers conduct randomized controlled trials, in which people with a given problem or disorder are randomly assigned to one or more treatment groups or to a control group. Sometimes the results of randomized controlled trials have been startling. After natural or human-caused disasters, therapists often arrive on the scene to treat survivors for symptoms of trauma. In an intervention called critical incident stress debriefing (CISD), survivors gather in a group for “debriefing,” which generally lasts from 1 to 3 hours. Participants are expected to disclose their thoughts and emotions about the traumatic experience, and the group leader warns members about possible traumatic symptoms that might develop.

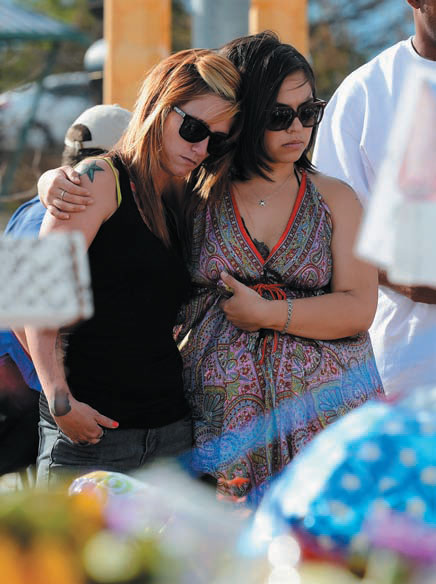

Two young women comfort each other at a makeshift memorial for the victims of a shooting spree that left 12 dead and 58 wounded at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado. It is widely believed that most survivors of any disaster will need the help of therapists to avoid developing posttraumatic stress disorder. Does the evidence support this belief? What do randomized controlled studies show?

Yet randomized controlled studies with people who have been through terrible experiences—including burns, accidents, miscarriages, violent crimes, and combat—find that posttraumatic interventions can actually delay recovery in some people (van Emmerik et al., 2002; McNally, Bryant, & Ehlers, 2003; Paterson, Whittle, & Kemp, 2015). In one study, victims of serious car accidents were followed for 3 years; some had received the CISD intervention and some had not. As you can see in Figure16.2, almost everyone had recovered in only 4 months and remained fine after 3 years. The researchers then divided the survivors into two groups: those who had had a highly emotional reaction to the accident at the outset (“high scorers”), and those who had not. For the latter group, the intervention made no difference; they improved quickly.

Figure 16.2

Do Posttraumatic Interventions Help...or Harm?

Victims of serious car accidents were assessed at the time of the event, 4 months later, and 3 years later. Half received a form of posttraumatic intervention called critical incident stress debriefing (CISD); half received no treatment. As you can see, almost everyone had recovered within 4 months, but one group had higher stress symptoms than everyone else, even after 3 years: the people who were the most emotionally distressed right after the accident and who received CISD. The therapy actually impeded their recovery (Mayou et al., 2000).

Now look at what happened to the people who had been the most traumatized by the accident: If they did not get CISD, they were fine in 4 months, too, like everyone else. But for those who did get the intervention, CISD actually blocked improvement, and they had higher stress symptoms than all the others in the study even after 3 years. The researchers concluded that “psychological debriefing is ineffective and has adverse long-term effects. It is not an appropriate treatment for trauma victims” (Mayou et al., 2000). The World Health Organization, which deals with survivors of trauma around the world, has officially endorsed this conclusion.

You can see, then, why the scientific assessment of psychotherapeutic claims and methods is so important.

When Therapy Helps

LO 16.3.B Provide examples of areas in which cognitive and behavior therapies have shown themselves to be particularly effective.

Listen to the Audio

We turn now to the evidence showing the benefits of psychotherapy and which therapies work best in general, and for which disorders in particular (e.g., Chambless & Ollendick, 2001). For many problems and most emotional disorders, cognitive and behavior therapies have emerged as the method of choice (Hofmann et al., 2012):

Depression. Cognitive therapy’s greatest success has been in the treatment of mood disorders, especially depression (Beck, 2005), and people in cognitive therapy are less likely than those on drugs to relapse when the treatment is over. The reason may be that the lessons learned in cognitive therapy last a long time after treatment, according to follow-ups done from 15 months to many years later (Hayes et al., 2004; Hollon, Thase, & Markowitz, 2002; Seligman et al., 1999; Watts et al., 2015).

Suicide attempts. In a randomized, controlled study of 120 adults who had attempted suicide and had been sent to a hospital emergency room, those who were given 10 sessions of cognitive therapy, in comparison to those who were simply given the usual follow-up care (being tracked and given referrals for help), were only about half as likely to attempt suicide again in the next 18 months. They also scored significantly lower on tests of depressive mood and hopelessness (Brown et al., 2005; Ougrin et al., 2015).

Anxiety disorders. Exposure techniques are more effective than any other treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder, agoraphobia, and specific phobias such as fear of dogs or flying. Cognitive-behavioral therapy is often more effective than medication for panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and obsessive–compulsive disorder (Adams et al., 2015; Mitte, 2005; Otto et al., 2009; Watts et al., 2015).

Anger and impulsive violence. Cognitive therapy is often successful in reducing chronic anger, abusiveness, and hostility, and it also teaches people how to express anger more calmly and constructively (Deffenbacher et al., 2003; Hoogsteder et al., 2015).

Health problems. Cognitive and behavior therapies are highly successful in helping people cope with pain, chronic fatigue syndrome, headaches, and irritable bowel syndrome; quit smoking or overcome other addictions; recover from eating disorders such as bulimia and binge eating; overcome insomnia and improve their sleeping patterns; and manage other health problems (Butler et al., 1991; Crits-Christoph, Wilson, & Hollon, 2005; Davis et al., 2015; Stepanski & Perlis, 2000).

Childhood and adolescent behavior problems. Behavior therapy is the most effective treatment for behavior problems that range from bed-wetting to impulsive anger, and even for problems that have biological origins, such as autism (Hoogsteder et al., 2015; Scarpa, Williams, & Attwood, 2013; Sukhodolsky et al., 2013).

Relapses. Cognitive-behavioral approaches have also been highly effective in reducing the rate of relapse among people with problems such as substance abuse, depression, or sexual offending, and even schizophrenia (Hutton et al., 2014; Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004).

However, no single type of therapy can help everyone. In spite of their many successes, behavior and cognitive therapies have had failures, especially with people who are unmotivated to carry out a behavioral or cognitive program or who have ingrained personality disorders and psychoses. Also, cognitive-behavioral therapies are designed for specific, identifiable problems, but sometimes people seek therapy for less clearly defined reasons, such as wishing to introspect about their feelings or explore moral issues.

There is also no simple rule for how long therapy needs to last. Sometimes a single session of treatment is enough to bring improvement, if it is based on sound psychotherapeutic principles. A therapy called motivational interviewing, which focuses specifically on increasing a client’s motivation to overcome problems such as drinking, smoking, and binge eating, has been shown to be effective in as few as one or two sessions (Burke et al., 2003; Cassin et al., 2008; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). The therapist essentially puts the client into a state of cognitive dissonance: “I want to be healthy and I see myself as a smart, competent person, but here I am doing something stupid and self-defeating. Do I want to feel better or not?” The therapist then offers the client a cognitive and behavioral strategy of improvement (Wagner & Ingersoll, 2008). Some problems, however, are chronic or particularly difficult to treat and respond better to longer therapy. According to one meta-analysis that included eight randomized, controlled studies, long-term psychodynamic therapy (lasting a year or more) can be more effective than short-term approaches for complex mental problems and chronic personality disorders (Leichsenring & Rabung, 2008).

Furthermore, some people and problems require combined approaches. Young adults with schizophrenia are best helped by combining medication with family-intervention therapies that teach parents behavioral skills for dealing with their troubled children, and that educate the family about how to cope with the illness constructively (Elis, Caponigro, & Kring, 2013; Goldstein & Miklowitz, 1995). In studies over a 2-year period, only 30 percent of the patients with schizophrenia in such family interventions relapsed compared to 65 percent of those whose families were not involved. The same combined approach—medication and family-focused therapy—also reduces the severity of symptoms in adolescents with bipolar disorder and delays relapses (Miklowitz, 2007).

Special Problems and Populations Some therapies are targeted for the problems of particular populations. Rehabilitation psychologists are concerned with the assessment and treatment of people who are physically disabled, temporarily or permanently, because of chronic pain, physical injuries, epilepsy, addictions, or other conditions. They conduct research to find the best ways to teach disabled people to live independently, improve their motivation, enjoy sex, and follow healthy regimens. Because more people are surviving traumatic injuries and living long enough to develop chronic medical conditions, rehabilitation psychology is one of the fastest-growing areas of health care.

The use of animals in rehabilitation therapy, to help people with a variety of mental and physical problems, has been growing.

Other problems require more than one-on-one help from a psychotherapist. Community psychologists set up programs at a community level, often coordinating outpatient services at local clinics with support from family and friends. Some community programs help people who have severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, by setting up group homes that provide counseling, job and skills training, and a support network. Without such community support, many people with mental illness are treated at hospitals, released to the streets, and stop taking their medications. Their psychotic symptoms return, they are rehospitalized, and a revolving-door cycle is established.

A community intervention called multisystemic therapy(MST) has been highly successful in reducing teenage violence, criminal activity, drug abuse, and school problems in troubled inner-city communities. Its practitioners combine family-systems techniques with behavioral methods, but apply them in the context of forming “neighborhood partnerships” with local leaders, residents, parents, and teachers (Henggeler et al., 1998; Swenson et al., 2005; Tiernan et al., 2015). The premise of multisystemic therapy is that because aggressiveness and drug abuse are often reinforced or caused by the adolescent’s family, classroom, peers, and local culture, you cannot successfully treat the adolescent without also “treating” his or her environment. Indeed, MST has been shown to be more effective than other methods on their own (Schaeffer & Borduin, 2005).

BIOLOGY and Psychotherapy

Listen to the Audio

One of the longest debates in the history of treating mental disorders has been over which kind of treatment is better: medical or psychological. This debate rests on a common but mistaken assumption: If a disorder appears to have biological origins or involve biochemical abnormalities, then biological treatments must be most appropriate. In fact, however, changing your behavior and thoughts through psychotherapy or simply by having other new experiences can also change the way your brain functions, just as the expectations associated with a placebo can.

This fascinating link between mind and brain was first illustrated dramatically in PET-scan studies of people with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Among those who were taking the SSRI Prozac, the metabolism of glucose in a critical part of the brain decreased, suggesting that the drug was having a beneficial effect by “calming” that area. But exactly the same brain changes occurred in patients who were getting cognitive-behavioral therapy and no medication (Schwartz et al., 1996). Other studies have shown that CBT produces predictable EEG changes in neural activity in the brains of people undergoing this form of therapy, changes associated with the reduction of symptoms of depression and anxiety (Miskovic et al., 2011).

Moreover, even when medications are beneficial, they are rarely sufficient as “cures.” People who are depressed because of difficulties in their lives may get a lift from an antidepressant, but the pill will not teach them how to manage those difficulties. In recent years, prominent people have “come out,” admitting that they suffer from severe mental disorders and describing what it took for them to survive (see Temple Grandin’s [2010] account of her autism and Elyn Saks’s [2007] riveting story of learning to live with schizophrenia). What these accounts reveal is that even when medication helps, it is a relatively small part of the program of activities, support, and therapy needed for functioning in the world. One man with bipolar disorder told his psychotherapist: “Lithium cuts out the highs as well as the lows. I don’t miss the lows, but I gotta admit that there were some aspects of the highs that I do miss. It took me a while to accept that I had to give up those highs. Wanting to keep my job and my marriage helped!” (quoted in Kring et al., 2010). The drug alone could not have helped this man learn to live with his illness.

When Therapy Harms

LO 16.3.C Discuss four ways in which therapy has the potential to harm clients, and give an example of each.

Listen to the Audio

In a tragic case that made news around the world, police arrested four people on charges of recklessly causing the death of 10-year-old Candace Newmaker during a session of “rebirthing” therapy. (The procedure supposedly helps adopted children form attachments to their adoptive parents by “reliving” birth.) The child was completely wrapped in a blanket (the “womb”) and was surrounded by large pillows. The therapists then pressed in on the pillows to simulate contractions and told the girl to push her way out of the blanket over her head. Candace repeatedly said that she could not breathe and felt she was going to die. But instead of unwrapping her, the therapists said, “You’ve got to push hard if you want to be born—or do you want to stay in there and die?” Candace lost consciousness and was rushed to a local hospital, where she died. Connell Watkins and Julie Ponder, unlicensed social workers who operated the counseling center, went to prison for reckless child abuse resulting in death.

Troubled teens attend a boot camp designed as an intervention for delinquent behavior. Results from carefully controlled studies indicate the success of such interventions is questionable, at best.

Candace’s tragic story is an extreme example, but every treatment and intervention carries some risks, and that includes psychotherapy (Koocher, McMann, & Stout, 2014). In a small percentage of cases, a person’s symptoms may actually worsen, the client may become too dependent on the therapist, or the client’s outside relationships may deteriorate (Lilienfeld, 2007). The risks to clients increase with any of the following:

The use of empirically unsupported, potentially dangerous techniques. “Rebirthing” therapy was born (so to speak) in the 1970s, when its founder claimed that, while taking a bath, he had reexperienced his own traumatic birth. But the basic assumptions of this method—that people can recover from trauma, insecure attachment, or other psychological problems by “reliving” their emergence from the womb—are contradicted by the vast research on infancy, attachment, memory, and posttraumatic stress disorder and its treatment. Besides, why should anyone assume that being born is traumatic? Isn’t it pretty nice to be let out of cramped quarters and see daylight and beaming parental faces?

Rebirthing is one of a variety of practices, collectively referred to as “attachment therapy,” that are based on the use of harsh tactics that allegedly will help children bond with their parents. These techniques include withholding food, isolating the children for extended periods, humiliating them, pressing great weights upon them, and requiring them to exercise to exhaustion (Mercer, Sarner, & Rosa, 2003). However, abusive techniques are ineffective in treating behavior problems and often backfire, making the child angry, resentful, and withdrawn. They are hardly a way to help an adopted or emotionally troubled child feel more attached to his or her parents.

Table16.1 lists a number of therapies that have been shown, through randomized controlled trials or meta-analysis, to have a significant risk of harming clients.

Table 16.1

Potentially Harmful Therapies

| Intervention | Potential Harm |

|---|---|

| Critical incident stress debriefing (CISD) | Heightened risk of emotional symptoms |

| Scared Straight interventions | Worsening of conduct problems |

| Facilitated communication | False allegations of sexual and child abuse |

| Attachment therapies | Death and serious injury to children |

| Recovered-memory techniques (e.g., dream analysis) | Induction of false memories of trauma, family breakups |

| “Multiple personality disorder”–oriented therapy | Induction of “multiple” personalities |

| Grief counseling for people with normal bereavement reactions | Increased depressive symptoms |

| Expressive-experiential therapies | Worsening and prolonging painful emotions |

| Boot-camp interventions for conduct disorder | Worsening of aggression and conduct problems |

| DARE (Drug Abuse and Resistance Education) | Increased use of alcohol and other drugs |

Source: Based on Lilienfeld (2007).

Inappropriate or coercive influence, which can create new problems for the client. In any successful therapy, the therapist and client come to agree on an explanation for the client’s problems. Of course, the therapist will influence this explanation, according to his or her training and philosophy. Some therapists, however, cross the line. They so zealously believe in the prevalence of certain problems or disorders that they actually induce the client to produce the symptoms they are looking for (Mazzoni, Loftus, & Kirsch, 2001; McHugh, 2008; Nathan, 2011). Therapist influence, and sometimes outright coercion, is a likely reason for the huge numbers of people who were diagnosed with multiple personality disorder in the 1980s and 1990sand for an epidemic of recovered memories of sexual abuse during this period.

Prejudice or cultural ignorance on the part of the therapist. Some therapists may be prejudiced against some clients because of the client’s gender, culture, religion, or sexual orientation. They may be unaware of their prejudices, yet express them in nonverbal ways that make the client feel ignored, disrespected, and devalued (Sue et al., 2007). A therapist may also try to induce a client to conform to the therapist’s standards and values, even if they are not appropriate for the client or in the client’s best interest. For many years, gay men and lesbians who entered therapy were told that homosexuality was a mental illness that could be cured. Some of the so-called treatments were harsh, such as electric shock for “inappropriate” arousal. Although these methods were discredited decades ago (Davison, 1976), other “reparative” therapies (whose practitioners claim they can turn gay men and lesbians into heterosexuals) continue to surface. But there is no reliable empirical evidence supporting these claims, and both the American Psychological Association and the American Psychiatric Association oppose reparative therapies on ethical and scientific grounds. The former organization has issued “Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Clients” (2012).

Sexual intimacies or other unethical behavior on the part of the therapist. The ethical guidelines of both APAs prohibit therapists from having any sexual intimacies with their clients or violating other professional boundaries. Occasionally, some therapists behave like cult leaders, persuading their clients that their mental health depends on staying in therapy and severing their connections to their “toxic” families (Watters & Ofshe, 1999). Such psychotherapy cults are created by the therapist’s use of techniques that foster the client’s isolation, prevent the client from terminating therapy, and reduce the client’s ability to think critically.

To avoid these risks and benefit from what good, effective psychotherapy has to offer, people looking for the right therapy must become educated consumers, willing to use the critical-thinking skills we have emphasized throughout this book.

Modern psychotherapy has been of enormous value to many people. But psychotherapists themselves have raised some provocative questions about the values inherent in what they do. How much personal change is possible? Does psychotherapy promote unrealistic notions of endless happiness and complete self-fulfillment? Many Americans have an optimistic, let’s-fix-this-fast attitude toward all problems. In contrast, Eastern cultures have a less optimistic view of change, and they tend to be more tolerant of events they regard as being outside of human control. And, as we saw earlier in this chapter, some Western psychotherapists teach techniques of mindfulness and greater self-acceptance instead of self-improvement (Hayes et al., 2004; Kabat-Zinn, 1994).

In the hands of an empathic and knowledgeable practitioner, psychotherapy can help you make decisions and clarify your values and goals. It can teach you new skills and new ways of thinking. It can help you get along better with your family and break out of destructive family patterns. It can get you through bad times when no one seems to care or to understand what you are feeling. It can teach you how to manage depression, anxiety, and anger.

However, despite its many benefits, psychotherapy cannot transform you into someone you’re not. It cannot turn an introvert into an extrovert. It cannot cure an emotional disorder overnight. It cannot provide a life without problems. And it is not intended to substitute for experience—for work that is satisfying, relationships that are sustaining, activities that are enjoyable. As Socrates knew, the unexamined life is not worth living. Yet, as we would add, the unlived life is not worth examining.